Some of Japan’s ‘nuclear refugees’ can finally go home — but they don’t want to

Children play near a Geiger counter that monitors radiation at a kindergarten about 30 miles from the tsunami-crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. The government is increasingly pushing families displaced by the disaster to return to their homes.

When an earthquake shook Japan on March 11, 2011, followed quickly by a huge tsunami, a young mother named Kazumi packed an overnight bag and some toys for her kids.

This was before the disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, and Kazumi was just getting her family away from the storm. It was supposed to be a day trip, but Kazumi has lived in Tokyo ever since.

Four years since that triple disaster struck the Tohoku region of northern Japan, there are still more than 220,000 refugees from the area scattered over the country. That includes everyone who lived within an approximately 30-kilometer radius of the plant; the Japanese government ordered them out of their homes. But they weren’t the only ones who fled.

Many others, like Kazumi, lived just outside the mandatory evacuation zone. They were allowed to stay, but they figured their homes were still too close to the reactor for comfort.

Such people are pointedly referred to as “voluntary evacuees," and they face growing derision from the media, their communities and even the government, which wants people in the areas they’ve officially “restored” to go home. That's why "Kazumi," like just about every evacuee I meet, insists on using a false name.

Kazumi's home in the town of Iwaki-shi is still standing. Her husband even stayed while she and her children left for Tokyo. He kept his teaching job to support the family, but "over time he got really depressed," Kazumi says.

He would constantly measure radiation levels and warn his students that there was contamination. But after a while, she says, “people called him a liar. They’d say, 'The government and their elite scientists say there’s nothing to worry about. Who are you to spread those falsehoods?'”

But the Geiger counter is a machine, Kazumi points out. It doesn't lie in the same way humans can.

After two years, her husband couldn’t take it anymore. He joined them in Tokyo and found a job, though no longer as a university researcher. But Kazumi says she’s lucky because her family is together. A lot of other dads stayed behind in Fukushima to support their wives and children, living the so-called hinan seikatsu — evacuee life.

The Japanese government has given Kazumi free housing for four years, but that’s supposed to end next March. She's wracked with worries about where her family will live, especially knowing the difficult choices other Fukushima refugees have had to make: Stay and possibly get sick from radiation? Raise your kids without a dad? A lot of her friends have gotten divorced, their marriages broken by the stress.

Official announcements say places like Iwaki-shi are now just as safe as Tokyo. But Kazumi says she measured the radioactivity of the dirt that had piled up on her veranda last summer, and levels were still high.

It's actually not surprising that, especially recently, government numbers have been low: Government monitoring posts are frequently in places that have been paved over and cleaned, and radioactive cesium is water soluble. But children don’t play on concrete slabs, and you never know which way the wind will blow.

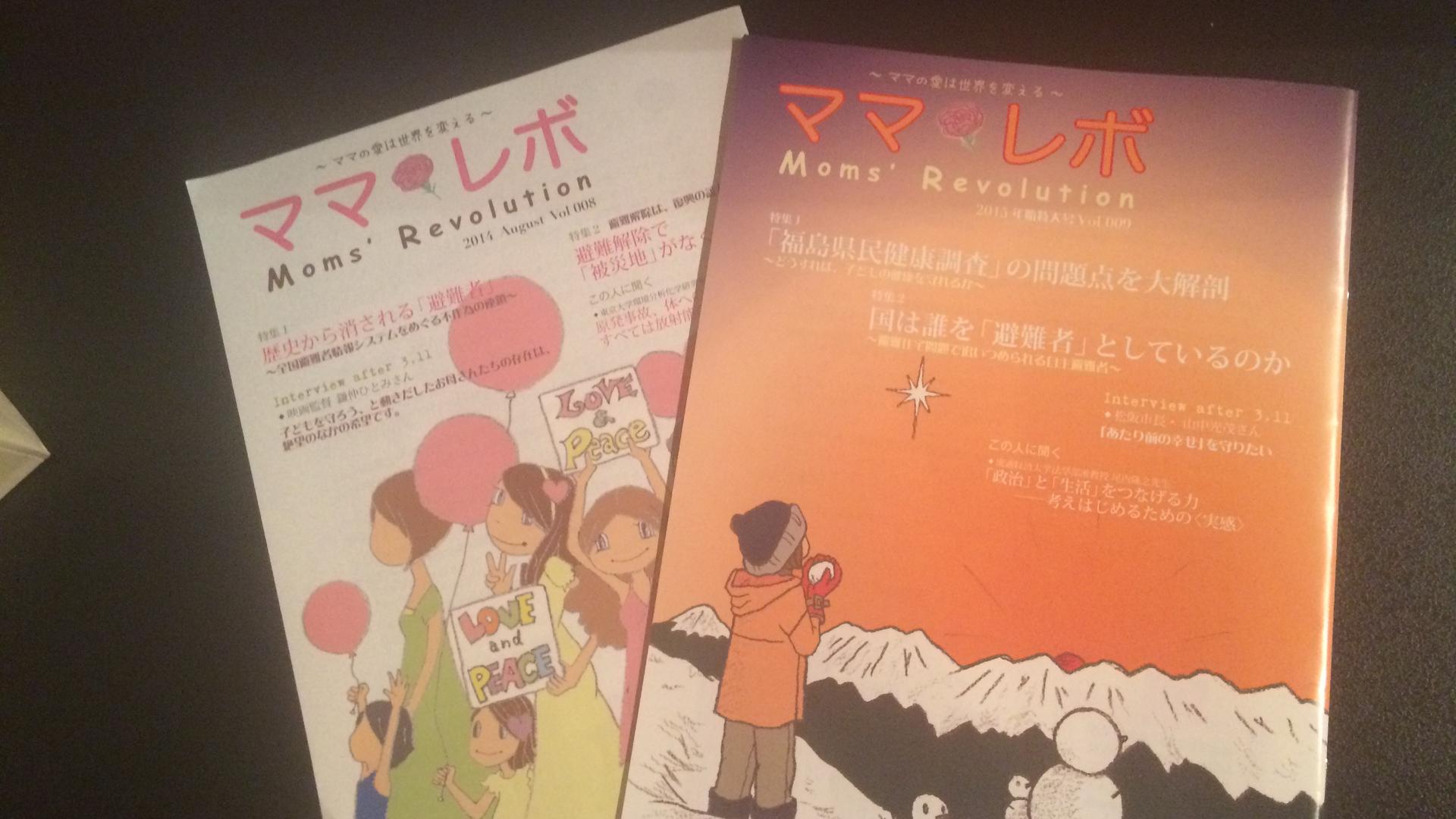

Last year, a popular comic published a story about how kids in Fukushima were having unusual nosebleeds, linking them to radiation exposure. Government officials, including the prime minister, went out of their way to slam the comic, calling it untrue and “rude” to the people of Fukushima.

But experts says government efforts to move soil have been haphazard and the cleanup processes opaque. And there's more than the nosebleeds: Thyroid cancer rates among kids in Fukushima have also spiked.

“The first point that nobody is willing to say is that the whole region has measurable levels of radioactive contamination," says Dr. Tim Mousseau, co-director of the Chernobyl + Fukushima Research Initiative.

He and other researchers say there simply hasn't been enough research on the effects of radiation to make any conclusive links to the nosebleeds or cancer. But the dangers are clear, he says: “There is no level of extra radiation that is safe."

So until the town is returned to the way it was, Kazumi doesn’t want to go back — even as she acknowledges it probably won’t happen in her lifetime.

She and other parents also worry about future discrimination if people find out where their kids are from. Fukushima, she points out, has become infamous, just like Chernobyl. “Who wants to marry someone possibly tainted by radiation?” she wonders.

Kazumi's eldest son recently had his elementary school graduation essay rejected. He wrote about his misgivings about where the government is taking the country.

His teacher was nice about it, he says. She said she’d work with him to rewrite the essay so that it wasn’t critical of the government. But "criticism of the government was at the core of the essay," he says. He’s not going to hand in a watered-down version. He’ll turn in something else.

When I ask him what he wants to be when he grows up, he doesn't miss a beat. “I want to be a member of Parliament," says the precocious 12-year-old. "I want to change Japan.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!