‘When I heard that ISIS is bulldozing the ancient city of Nimrud, I cried’

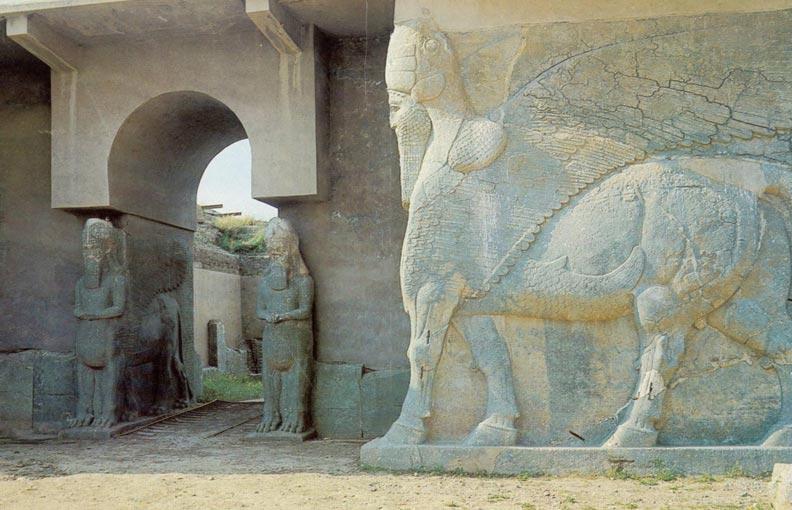

Some of the art at risk in Nimrud.

When I heard the news that ISIS is bulldozing the ancient city of Nimrud, I cried.

I am clinging to the hope that this is just propaganda from the Iraqi government to further blacken the name of the ISIS. After all, there have been no pictures or videos of any destruction, nor any claim or comment by ISIS.

But ISIS has already destroyed a multitude of historical artifacts and archaeological sites as part of its campaign against what they call paganism and idolatry. So the odds are against all of us who hold dear the common heritage of mankind.

The destruction of Nimrud would take ISIS' culture war to a whole new level. The reports of its demise have brought an avalanche of international criticism; UNESCO, the UN's cultural preservation agency, says there’s no doubt that it would be a war crime.

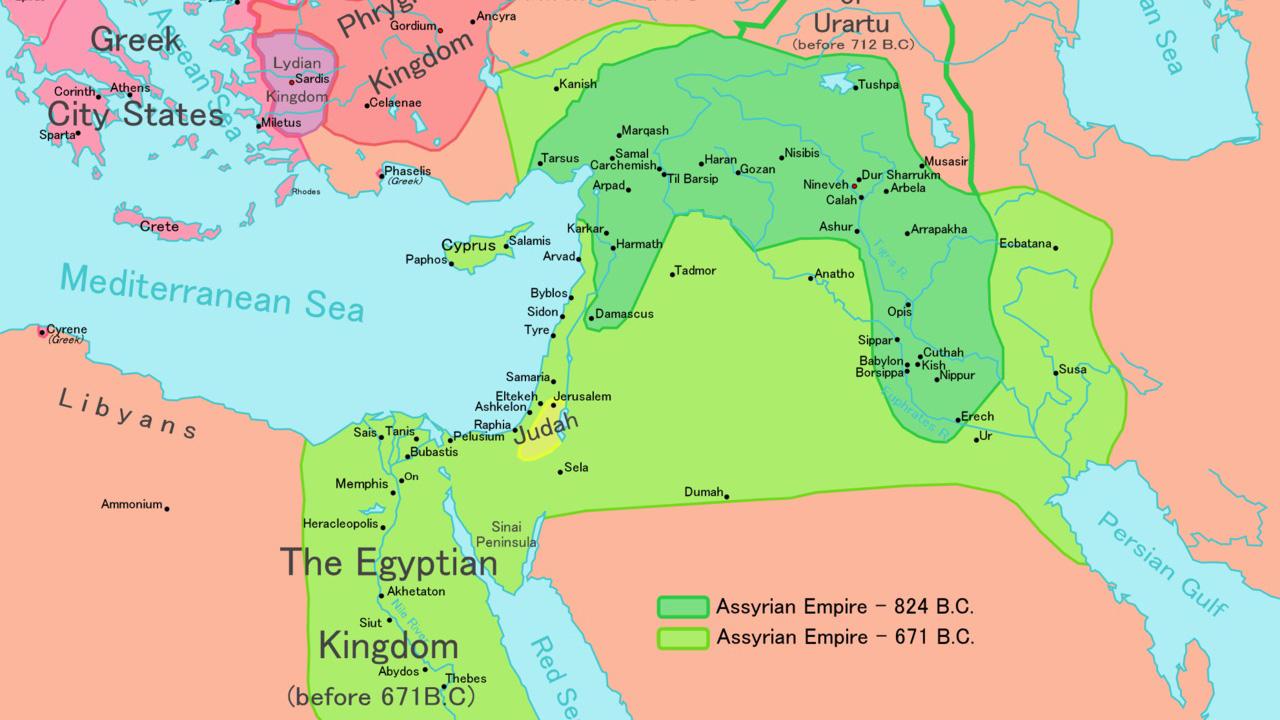

They say Nimrud represents part of the common heritage of humanity. Western civilization traces its roots to the first agricultural civilizations in what we call the Fertile Crescent. They were the scene of the first laws, the first writing and new forms of government beyond the village and tribal level.

Time is not kind to historical sites: Fires, floods, earthquakes and simple erosion alone are constant threats. It seems unbelievable that anyone would deliberately attempt to destroy a place of such beauty and significance, a site that’s survived not only nature but the Crusades, the Mongols, both world wars and countless conflicts between the Persians and the Turks.

Nimrud lies about 20 miles southeast of Mosul. It was founded by the king of the Assyrians — one of a succession of empires in what historians call the Fertile Crescent — in about 1250 BC, more than 3,000 years ago. Just to put that date in perspective, that was just 150 years after the death of Moses.

Nimrud’s actual name was Kalhu, and was recorded in the Bible as Calah. It was not called Nimrud until the 18th century AD, when a western explorer mistakenly associated the site with the Biblical character named Nimrud, who appears in the Book of Genesis and the Chronicles.

Kalhu became the capital of the Assyrian empire around 850 BC, when the Assyrian empire was on one its upswings. It remained the capital for about 150 years.

I've never been lucky enough to visit the site myself, but I have seen the colossal statues — known as "lamassus" — of winged man-lions and man-bulls and reliefs in London's British Museum and the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. Other artifacts can be seen everywhere from Chicago and Paris to Baghdad and Mosul.

Kalhu may have held as many as 100,000 people, which is pretty staggering when you realize that northern Europeans were all living in mud-hut villages at that time. The main Royal palace alone covered 12 acres.

It was a state of laws, and it established eastern Aramaic as the lingua franca for the Middle East. Jesus probably spoke something similar to Kalhu's residents.

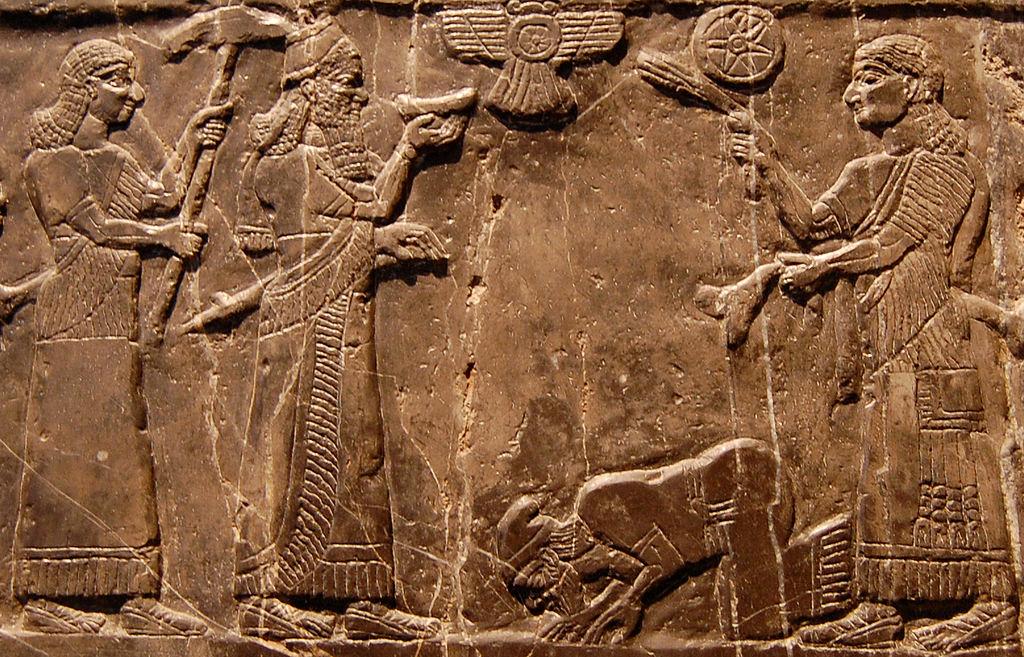

But we shouldn't look at the Assyrians through rose-tinted spectacles. Like all empires, the Assyrian Empire was built on violent conquest. Many of the monuments at Kalhu commemorate great victories and the torture and massacre of Assyria's enemies.

The Assyrians fell into bitter civil wars in the 6th century BC. That allowed the Babylonians to re-emerge as the pre-eminent power in the Middle East. The demise of the Assyrians, and the end of Nimrud, therefore, roughly coincides with the exile of the Israelites to Babylon.

But the Assyrians did not disappear. The countryside around Nimrud is still populated by people who identify as Assyrians. They still speak Aramaic, and most practice Christianity rather than Islam. That might explain the hostility of ISIS, but, as UNESCO says, Nimrud is part of the common heritage of all mankind.

There are some glimmers of hope for the treasures of Kalhu. About 90 percent of the city is still underground and has not been excavated. Much of the art — the statuary and reliefs, gold, ivory and jewels — has been removed to museums over the last two centuries. But the aboveground structures, many of which still hold these priceless reliefs, are very vulnerable — and hopefully still in existence.