In the field of folk music, Alan Lomax is a giant — if a flawed and controversial one

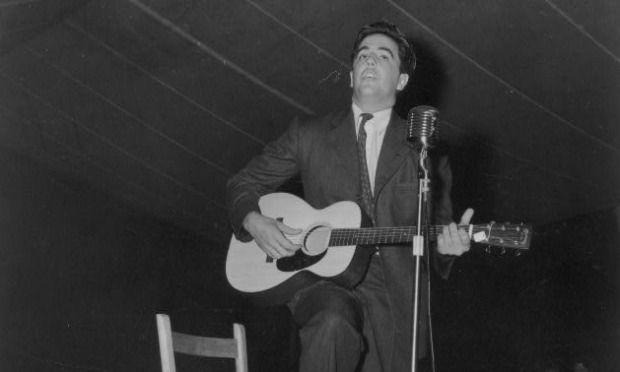

Alan Lomax performs at the Mountain Music Festival in Asheville, North Carolina.

Alan Lomax was a giant in the field of folklore. He was no singer, composer or even songwriter — just a collector. And his collection of recordings from Europe, Asia, the Caribbean and, especially, the American South is monumental

This year would have been his 100th birthday. Lomax's widest influence came from his trips to the rural South, where he sought out the acoustic folk blues sound that was still unknown to most Americans. Lomax's recordings came to influence generations of musicians around the world. Without him, we might never have had rock and roll as we know it.

Lomax started collecting as a teenager alongside his father, the folklorist John Lomax. This was at a time when the mainstream representation of African Americans was the radio show Amos 'n' Andy, in which white actors played stereotypes of black characters. "There certainly were not a lot of people who were interested in African American culture," says Patricia Turner, a folklorist at UCLA. Lomax, however, “thought that the everyday artistic expression of African Americans ought to be recorded and preserved.”

But Turner and some other scholars have come to question Lomax's influence. Lomax's emphasis on the blues, they believe, presented a distorted and stereotypical picture of blacks. Karl Hagstrom Miller, the author of Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow, says when Lomax arrived in a black community, he didn't ask for "'the songs that you enjoy singing.' He asked for them to find songs that fit into his idea of old time folk songs."

If a man gave him a Tin Pan Alley number or a church song, Lomax wasn't terribly interested. It would take 14 years before Lomax ever recorded in a black church and he never recorded at a black college. Consequently, in this body of recordings, "you have no opportunity to hear what middle class African Americans are into," Miller says, "or upper-class African Americans or urban African Americans."

For Lomax, the locus of authentic black expression was best found in prisons. "The black communities were just too difficult to work in with any efficiency and so my father had the great idea that probably all of the sinful people were in jail," Lomax once said. "And that's where we found them — that's where we found this incredible body of music."

The people Lomax and his father approached were often reluctant to display their culture for an outsider with a recording machine. But when the Lomaxes were able to get the cooperation of a prison warden, their subjects could be coerced. "Presently the guard came out, pushing a Negro man in stripes along at the point of his gun," Lomax wrote about one session. "The poor fellow, evidently afraid he was to be punished, was trembling and sweating in an extremity of fear. The guard shoved him before our microphone."

Lomax wasn't ashamed of his methods: He saw prisoners as the people most sheltered from outside influences, and therefore most authentic. And much of the music he recorded this way, including many blues and work songs, are powerful expressions of overlooked cultures. But his quest for a pure black music untouched by white influences was problematic. "By nature of the close proximity that two different cultures have by living next to each other, it is inevitable that the music and the cultural products that they are producing are intertwined and interrelated," says Dwandalyn Reece, curator of music at the Smithsonian's National Museum of African-American History and Culture. Throughout the history of the South, she says, "People were singing each other's music, so to speak.”

Although Lomax celebrated his blues artists as creative geniuses and championed performers like Leadbelly, who had been imprisoned, Reece says that those musical choices affirmed negative and dangerous stereotypes. Lomax's selections suggested that "African-Americans are criminals [and] are illiterate. They are not serious, they are not smart. That 'authenticity' is rooted in having that kind of vision of what an African American can or cannot be."

But for Dom Flemons, a long-time member of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, the authenticity of Lomax's collecting is less important than the greatness of the musicians he captured. Flemons, who is African American, leans heavily on the Lomax repertoire in his own brand of traditional music. And without Lomax, it wouldn't exist. "A guy just sitting on the porch at home, playing and enjoying the music, is just him enjoying his music by himself," Flemons says. "But if you want to hear it on a record, someone has to record that."

Even Reece is, in the end, sympathetic to what Lomax was trying to achieve. "I think he was trying to — in his way — collect what was a true African American cultural form of expression. And we all, as researchers, have our own biases and perceptions and expectations. And that's part of the challenge of doing that kind of work."

The research for this story was supported by ArtsEdge, the Kennedy Center's K-12 arts education network. The story first aired on PRI's Studio 360 with Kurt Andersen,