For a group of Siberians, Hawaii was far from a tropical paradise

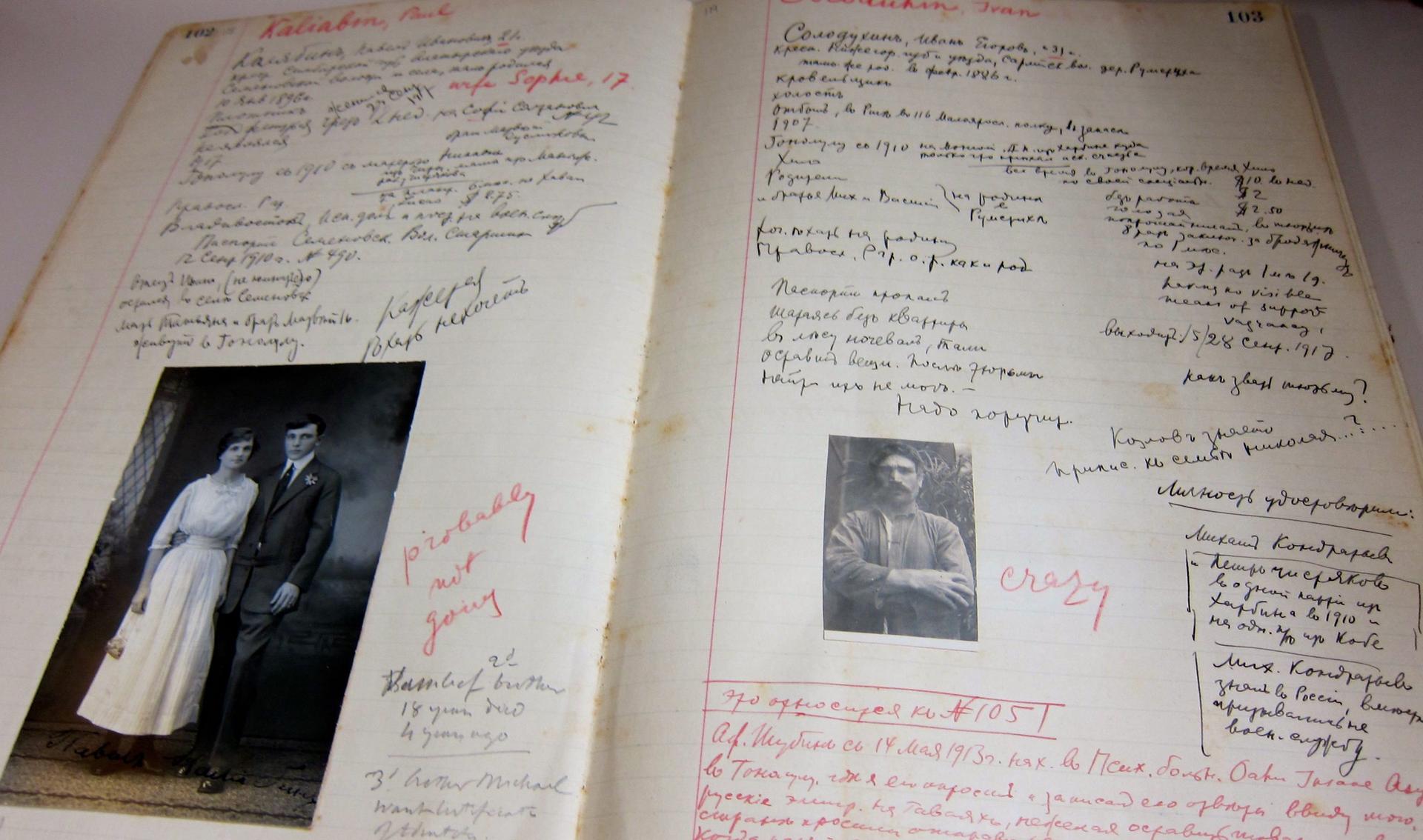

A Russian family migrating to Hawaii pose for a passport photo.

Four years ago, I went on a Hawaiian vacation. But I didn’t go snorkeling; I spent nearly all my time in the bowels of a university archive, browsing 100-year-old newspapers.

The truth is that I can only stand so much sand and sea. And when I happened to type two words into Google — "Russians" and "Hawaii" — I stumbled across a startling historical footnote.

At the turn of the last century, the Hawaiian Board of Immigration imported more than 1,500 Russians, mostly from Siberia, to work the islands’ sugar plantations. It was a last-ditch effort to make the then-US territory of Hawaii more white.

As Patricia Polansky, the Russian bibliographer at the University of Hawaii’s Hamilton Library explains, the planters first brought in Japanese and Chinese workers. Asian labor was the backbone of the early sugar industry, but working the sugarcane fields was a brutal way to make a living. In 1909, several thousand Japanese laborers went on strike demanding better pay and working conditions, which worried plantation owners.

“So they decided they wanted to try what we call haole labor, or white labor,” Polansky says.

A report issued by the Commissioner of Labor on Hawaii described local planters as “willing without reserve to employ all the Caucasian workers the government can bring to the islands, at a wage one-third larger” than what was paid Asian laborers.

“When the plantation owners were looking around for white groups, there happened to be in Honolulu a man named Perelstrous, who was a Russian kind of entrepreneur," Polansky says.

“Kind of” is the key term here. Perelstrous drew up a recruitment brochure for the Russians, and once he and his crew reached Russia, they launched a "huge, huge propaganda" effort, according to Amir Khisamutdinov, a historian at Far Eastern Federal University in Khabarovsk. "‘Oh, you need to come! We doing for you big, say, possibilities to work. Good weather…’”

“There were all kinds of things in there,” Polansky adds. “They would be given a little house, how many hours they had to work, what their wages would be.”

That, and one extra thing: The brochure also suggested the Russians would be given their own land.

“That actually didn’t turn out to be true, of course,” Polansky says. “They were coming just to work on the plantations. So that was part of what caused a lot of the trouble after the Russians got here.”

The Siberians probably imagined they were traveling to an island paradise. Instead, they ended up in quarantine after measles broke out on their steamer. Their encampment on a Honolulu wharf became a tourist draw, while the newspapers made a circus out of the immigration snafu. According to Khisamutdinov, a large part of this was due to communication failure.

“Language, it was a huge problem for Russians in Hawaii,” he says. The Russians didn’t have interpreters. In fact, there were so few Russian speakers in Hawaii that authorities recruited a local actress to help negotiate disputes, like one that broke out when the Russians tried bathing in the nude on a public beach.

And there wasn’t much cultural interpretation. Everything in Hawaii was totally alien to the Russians, from the local cuisine to the tropical weather. There was no community hub, no church, no expat ambassadors to help explain, as Khisamutdinov puts it, what their obligations were and how to enroll their children in schools.

“I think it’s the biggest mistake from authorities in Hawaii,” Khisamutdinov says. “They didn’t describe.”

The Russians fled Hawaii in droves. Many headed for California or New York, and a few returned to Russia.

But the story has another twist. Seven years after the Russians first arrived in Hawaii, the Russian Revolution took place. The new government, headed by Lenin, wanted the Russians in Hawaii to come home.

The scrapbook Troutshold compiled is filled with portraits and biographical sketches of the Russians who remained. It’s an extraordinary document, probably the only place you’ll find photos of Russian men with handlebar mustaches wearing Hawaiian work clothes.

Few people took Troutshold up on his offer of free passage to war-torn communist Russia, but some who did never forgot Hawaii. And when the Soviet Union collapsed several decades later, they reemerged.

“One day, I had a phone call from Catholic Charities,” Polansky says.

“There’s a Russian woman here,” they told her.

“I met her, and she was carrying an urn with her that had her mother’s ashes in it," Polansky says. "It happened to be that her mother was born here in Hawaii. She was a child of one of these people that came here to work on the plantations, but her family had decided to repatriate to Soviet Union.”

Years later, when her mother was on her deathbed, she told her daughter, “I want to be buried in Hawaii.” With the Iron Curtain in place, that didn’t seem likely. So she waited.

“The minute the Soviet Union collapsed, she put herself on an airplane and showed up in Hawaii with her mother’s ashes," Polanksy says.

Polansky and Khisamutdinov put the passport application album online and began to connect with even more families of the long-lost Russians of Hawaii. While their encounters with descendants haven't all been quite as dramatic as the first one, they have been contacted by about 30 descendants of people listed in the album so far.

It’s funny to think what might Hawaii might look like had the Russian immigration scheme succeeded. Would the islands be dotted with borscht stands today? Would balalaika jam bands be performing at the annual Island Arts Festival?

These are questions you can spend an entire tropical vacation contemplating. But this is a place where you can find sushi made from spam — I doubt there’s any influence Hawaii can’t absorb.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?