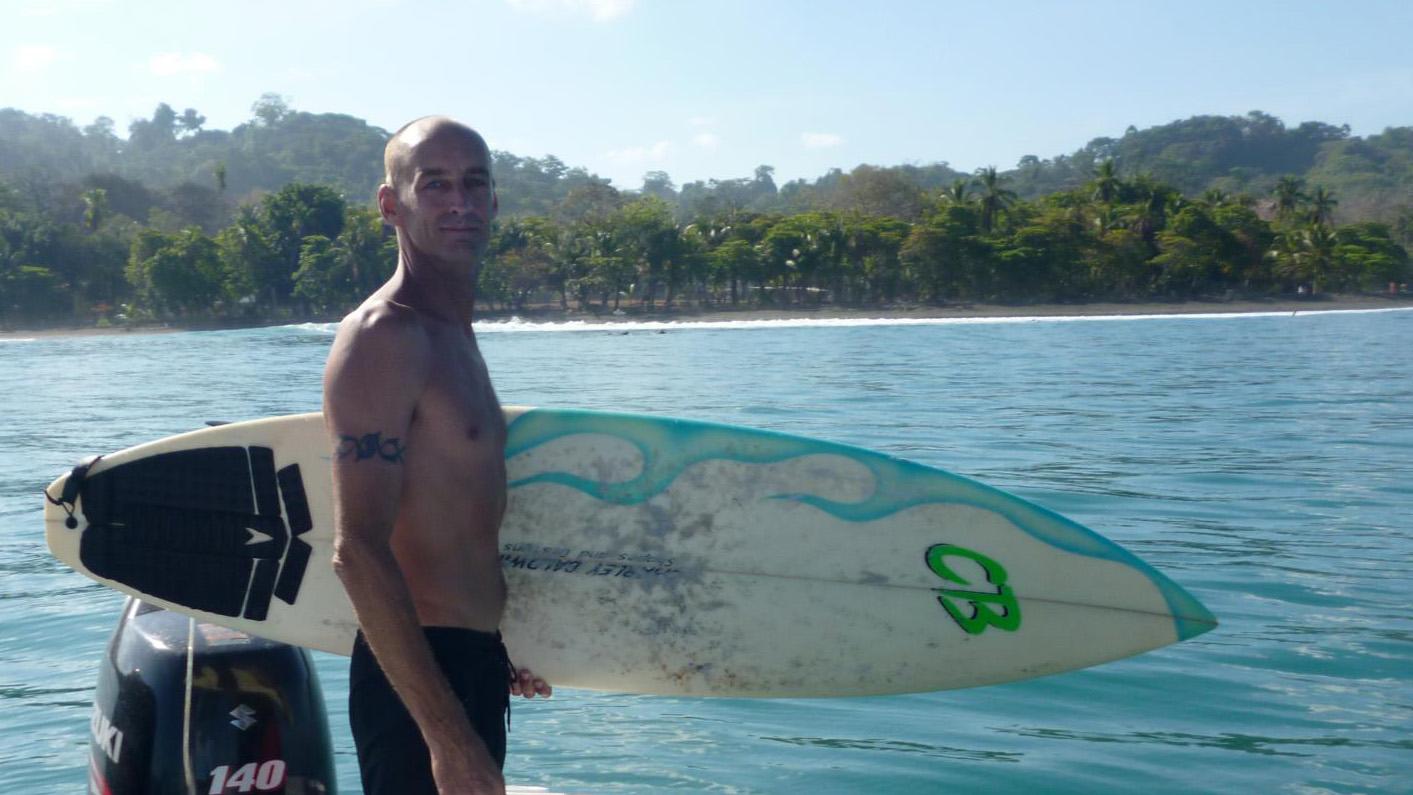

Dean Parker, a commercial housepainter and avid surfer from Florida, traveled to northern Iraq to fight with the Kurdish Peshmerga against ISIS.

Dean Parker was sitting on his couch one evening, relaxing after a long day at his job as a commercial painter. That's when he saw a news report about Kurds fighting on northern Iraq's Mount Sinjar, where ISIS had trapped thousands of people from the Yazidi religious sect.

“I made the decision right there after watching those news reports,” Parker recalls. “After watching it for an hour, I was very upset. And I was online booking a ticket.”

He packed body armor from a local military surplus shop, a sturdy pair of boots, clothes and his e-reader — loaded with a copy of Sun Tzu’s "The Art of War.” A month later, Parker was in Syria, fighting with Kurdish forces on the front line against ISIS.

He says he didn’t tell his family until he was already in Syria. “They were worried, you know messaging me: 'Come home, come home.' I told them I can’t. Not yet, anyways,” Parker says. “And after a couple days it sunk in and at they were very supportive."

Parker, a lanky 49-year-old who's an avid surfer and a grandfather, is one of at least a dozen Westerners who have traveled to the Middle East to take up arms against Islamist militants, who have hundreds of foreign fighters of their own.

Parker had no military experience, and was kept away from the most active front lines. But that’s not the case for many of the other Western fighters who have joined the peshmerga, the Kurdish military forces. A video posted online in December shows Canadian Dillon Hillier, who served in the Canadian military in Afghanistan, trying to help an injured fighter while under fire.

Parker says he met two other Americans among the dozen or so Western fighters. They didn't always have translators, but he says they did always find ways to communicate with their Kurdish counterparts.

Parker recalls the first time his unit, which included both Kurds and foreigners, came under fire. He was on guard duty on the roof.

“I go running back and I yell over the side of the wall at some of the other foreign fighters, like, ‘Ah, I’m getting shot at up here, what should I do?’” Parker remembers. “One said, 'Ducking would probably be a good idea.’ I started laughing and said, ‘OK, I’ll do that.’”

There is a general camaraderie among the Western recruits, Parker says, but other foreign fighters criticized him for being in a combat zone without military experience, saying it put others at risk.

And he insists that merely the presence of foreign fighters is a morale boost for the Syrian Kurdish troops.

“There is a famous Kurdish saying: 'We have no friends but the mountains.’ And that saying has always stuck,” Parker says. “And I thought … if I do nothing else, it’s someone coming all the way around the world to say, ‘Hey, you guys aren’t alone in this horrific fight here against these monsters. You know, people do care, so just the moral support.’”

But for Parker, morale is a bit lower these days. He’s staying in a modest hotel in Sulaymaniyah, another city in the Kurdish part of Iraq, trying to raise enough money to get a ticket home to Miami.

“I’m sure the Department of Homeland Security is going to want to have a talk with me. And the FBI is going to want to have a talk with me,” Parker says. “That’s understandable. I don’t have anything to hide."

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?