It’s Canada (again)! This time, it’s helping to lead the way to fix the environment

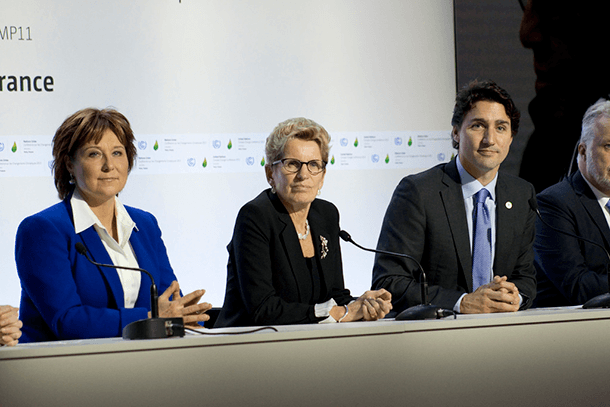

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at COP21

When Canada's newly elected Prime Minister Justin Trudeau came to Paris to participate in the worldwide environmental negotiations, he brought with him a clear message: Canada is now backing federal and provincial climate protection.

For many Americans, it's the latest sign that Canada's new leader, from welcoming Syrian refugees to quelling Islamophobia, is somehow representing an American ideal as well.

On the environment, Trudeau is breaking with Canada's recent past. After a decade under conservative leader Stephen Harper, who pulled out of the Kyoto Accord and championed oil sands development, Trudeau promises to do things differently. Some parts of Canada have already begun a new way of pricing carbon, he pointed out.

“A lot of you may have noticed that over the past 10 years or so, Canada has been perhaps less enthusiastic than some about addressing climate change and its impacts,” Trudeau said. “But even though at the federal level we haven’t necessarily been strong and active, at the subnational level our provinces have stepped up. We have four different provinces, representing about 86 percent of the Canadian economy, that have actually moved toward putting a price on carbon.”

Trudeau also stressed an idea that encouraged many participants at the Paris environment conference: renewable energy development and energy efficiency are now engines of economic growth.

“We are now in a race to see who can create the best technology for renewable energy, for moving forward in a way that understands there is no longer a choice to be made between what’s good for the economy and what’s good for the environment,” he said at COP21.

Putting a price on carbon is a key stimulant of green energy development, Trudeau says. This strategy is now well underway in several Canadian provinces. The province of Québec has been a leader, working with other provinces and even US states.

“We’ve set up a carbon market, which we've successfully linked to the one set up in California — creating the largest carbon market in North America — and we've been very successful at raising revenues,” says David Heurtel, Québec’s minister of sustainable development for the environment and the fight against climate hange.

Québec’s carbon market has raised close to a billion dollars, nearly a third of their target of $3 billion by 2020, Heurtel says. The money is reinvested entirely in Québec's Green Fund, which funds adaptation and mitigation measures like improved public transit, electrification of transportation, investments in renewable energy and development of the clean tech sector.

“Our carbon market is directly linked with our emissions reduction targets,” Heurtel says. “The current market allows us to achieve those reductions and is also a tool for economic development to transition out of a fossil fuel-based economy to a cleaner economy.”

The carbon pricing plan works like this: any major industrial company that emits more than 25,000 tons of CO2 per year, is, by law, automatically integrated into the carbon market. If the company wants to continue to emitting over 25,000 tons, it has to buy carbon credits.

Right now, the price is $17 Canadian per ton, which is about $12 or $13 US. And the price has been rising, Heurtel points out. In 2013, the price was closer to $10 Canadian.

“That’s the basis of a successful carbon market,” Heurtel explains, “because it creates the incentive for the private sector to change their ways. If a company buys carbon credits and then invests in cleaner technologies, then it can sell the unused credits on the open market and actually make money … and if the company also reduces emissions, it doesn’t have to buy as many credits."

Nobody was talking about carbon pricing in Canada five or 10 years ago, Heurtel says, but now five provinces, representing over 80 percent of Canada’s population, are looking seriously at carbon pricing.

A possible next step for Canada is working to integrate its system with the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a group of nine northeastern states in the US, including all four states that border Québec.

“There have been exchanges between WCI, which is the entity that governs the Québec-California market, and RGGI, to see if there could be some preliminary ways of aligning both markets,” Heurtel says. “So that's very exciting news.”

Washington State and Oregon are also interested in establishing carbon pricing or carbon markets that could be linked with the Québec-California model, Heurtel adds.

Mexico has also shown interest. Premier Couillard of Québec and Mexico’s president signed a Memorandum of Understanding on October 12 stating that both Québec and California would explore with Mexico the possibility of linking Mexico's carbon market, which should be online by 2017, with the Québec-California model.

“There is a lot of momentum,” Heurtel says. “There are a lot of things going on in the right direction. So it's a pretty exciting time right now.”

Heurtel disagrees with those who criticize carbon pricing as a way of leaving the door open to burning more carbon.

“That has not been our experience — quite the contrary,” he says. “Setting up the cap and trade system in Québec has helped us effectively reduce remissions and has effectively also helped business transition out of fossil fuel-based technologies and develop new technologies. They factored in the cost and they saw that there are actually opportunities for growth. Our economy now is positioning itself to be a leader in exporting these new technologies around the world.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?