Myanmar’s state-backed militias are flooding Asia with meth

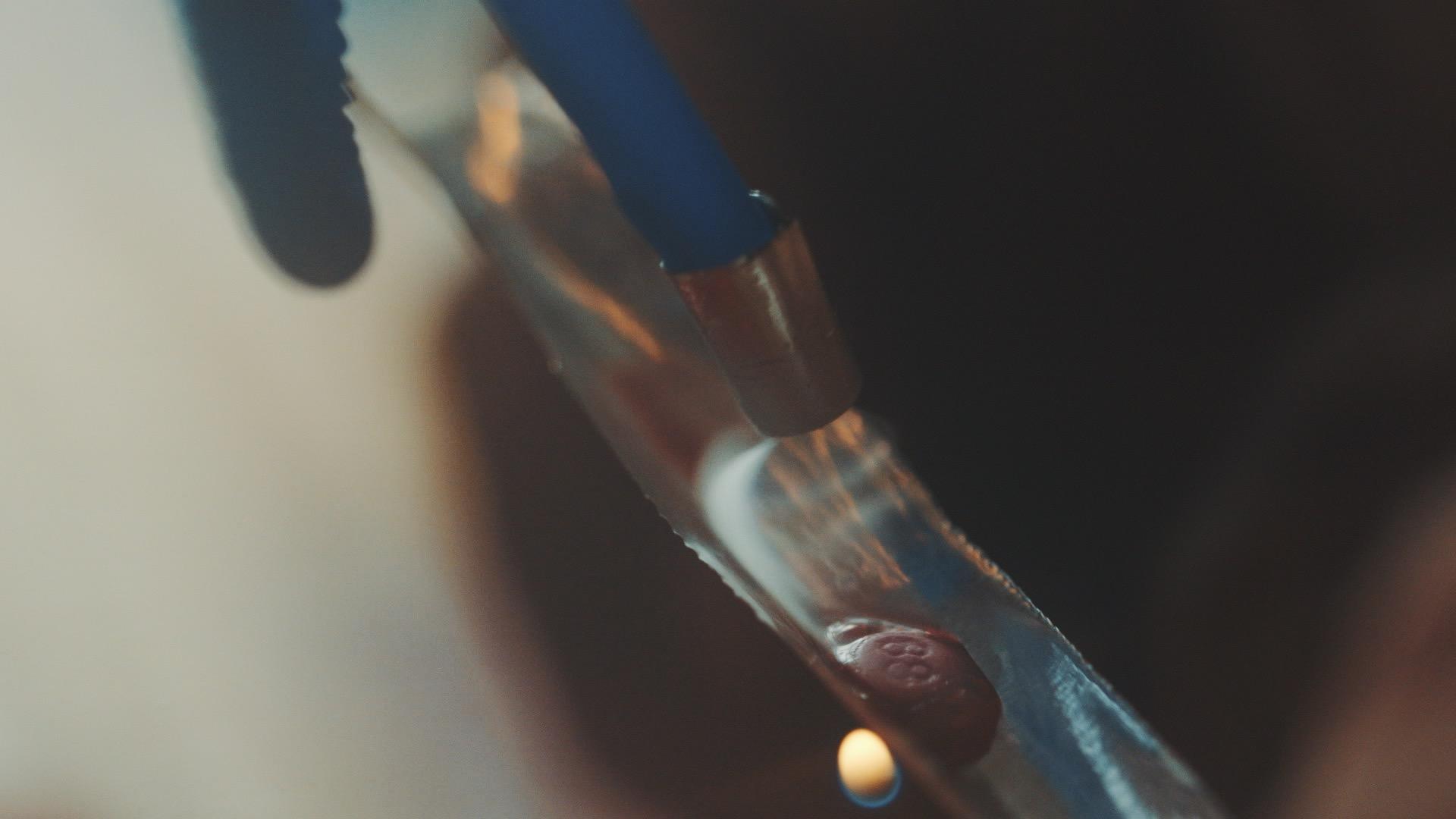

Smoke from a pink methamphetamine pill, heated on foil, rises into a water bong pipe in Myitkyina, Myanmar. Meth pills branded with the number "88" are believed to signify 1988, a celebrated year in which a popular uprising tried to oust Myanmar's hated military regime.

KACHIN STATE, Myanmar — It starts off as a typically sloppy Saturday night in Myanmar’s highlands. La Seng, 33 and shiftless, is getting blitzed in a sweltering room, surrounded by dark jungle, filling his belly with fish curry and cheap whiskey.

Then comes a terrifying buzzkill: a pack of 30 or more vigilantes, mounted on motorbikes, roaring down the muddy path leading to his shack.

The men wear helmets and fatigues. They grip bamboo rods. With military precision they swarm the room, bind La Seng’s thumbs with plastic ties and abduct him into the night.

La Seng, scraggly and dazed, is swept into a nearby Baptist church and forced onto his knees. He is encircled by growling men who call themselves “Patjasan,” members of a Christian anti-drug movement with a fearsome reputation among addicts.

“We’ll talk nicely to you at first,” they tell him. “And when that fails? We flog you.”

There was little sweet talk. This was a midnight interrogation with a foregone verdict: La Seng is a habitual meth user in need of salvation.

Exhibit A: One DIY meth bong, fashioned from a plastic bottle, fished out of his trash can. The vigilantes snarl and wave it under La Seng’s nose. His eyes flash like a cornered rodent's.

“It smells like meth!”

“But it’s not mine.”

“Idiot! Liar!”

An awful cracking sound rings off the walls. It’s a cane striking flesh on La Seng’s bony back. His body shudders and his voice turns meek.

Ordered to his feet, La Seng shuffles pitifully toward a wooden post. He is forced to shout a pledge — “I shall never use drugs again!” — while a stocky enforcer whips his back raw.

That night, La Seng sleeps uneasily on the church floor with his feet locked in medieval wooden stocks. A few vigilantes stand watch while the rest shuffle home to catch some sleep before the morning service.

Asia’s meth heartland

None of this is remotely legal. Even in Myanmar’s unruly highlands, hunting down addicts and beating them sober is a crime.

But so is producing methamphetamine, one of the region’s top commodities.

The drug has chewed through society and spat out broken men and women — all while the government responds with a collective shrug.

Myanmar’s northern region is a UK-sized territory encompassing states called Shan and Kachin. Bordering China and Thailand, it is an anarchic place controlled by dozens of armed factions split along ethnic lines, who vie for power over a mountainous backcountry.

This is the heartland of Asian meth production.

For decades, Myanmar has ranked among the world’s top producers of illicit drugs. Its heroin yield is second only to Afghanistan’s. When it comes to meth output, only Mexico’s cartels can compete.

Officially, Myanmar’s government has sworn to defeat this “drug menace.” Its military brashly promises the destruction of all narcotics in the country by the decade’s end.

But a nine-month GlobalPost investigation reveals that the government is quietly fueling the underground narcotics trade. Some of the trade’s new key players are, in fact, militias created by the army itself.

These narco-militias have emerged as a cheap solution to the army’s biggest challenge: defeating guerrilla rebels in the hills.

On the books, these militias are paid a pittance. But in return for holding down turf, a select few receive a tantalizing gift: freedom to get rich off black-market crime with impunity.

And no illicit business is as lucrative as the meth trade.

In years past, Myanmar’s hidden support for armed drug producers might be written off as just another blotch on a record that includes ethnic cleansing, drafting child soldiers and gunning down dissidents.

But not today. As Myanmar’s government seeks to overhaul its dismal image with the help of Western powers, this covert link to narco-militias presents a liability for the United States.

After a long and bitter enmity, the White House has emerged as one of Myanmar’s loudest supporters. America has started funding and training police in their dubious quest to defeat the so-called “drug menace” — even while the military props up militias that flood Asia with meth.

“The army is involved in various areas of the drug trade. Absolutely,” says John Whalen, former head of the US Drug Enforcement Agency office in Myanmar.

“Are they producing drugs? No. But they are providing tacit approval for drugs to be produced in these areas,” Whalen says. “And they’re benefiting from relationships with high-level traffickers.”

Meth rules

In much of Asia, meth is now the go-to drug. Pot doesn’t stand a chance.

There are 9.5 million meth users in Asia, according to UN officials, making the region the world’s largest market for the drug. The UN estimates that Myanmar’s militias crank out one to two billion meth tablets per year to satisfy this demand. That’s enough meth to get every man, woman and child in the United States high for an entire weekend.

Meth now accounts for more than 90 percent of drug arrests in Thailand, one of Asia’s largest drug consumers. Marijuana, at 5 percent, has been pushed to the fringe.

Rebel groups and pro-government militias alike run covert labs that supply Asia with its favorite illegal stimulant: hot-pink speed pills that offer a twitchy eight-hour high. From Myanmar’s jungles, the drug is smuggled to China’s chilly hilltops, Indonesia’s tropical isles and points in between.

Like cocaine in Peru, like heroin in Afghanistan, meth in Myanmar’s upcountry is pervasive and dirt-cheap — often selling for a mere $1 to $3 per pill. Along with heroin, the drug is further tormenting a region already shattered by hunger, isolation and guerrilla war.

“You can buy drugs anywhere, in any neighborhood, and the government does almost nothing,” says Peter Khon Awng, director of a Kachin State rehab center. “It’s tearing apart our families. It feels like a form of genocide.”

*****

This is the part of Myanmar unseen by backpackers and businessmen, who now flock to the nation in droves.

For decades, merely visiting Myanmar (formerly titled Burma) was taboo. The government’s habit of torturing critics and torching minorities’ villages left a stain on the country, ruled by a military dictatorship starting in the 1960s.

But Myanmar is suddenly hip. This facelift owes its success to an unlikely ally: the United States.

Not so long ago, the White House called Myanmar an “outpost of tyranny” and punished the nation with crushing sanctions.

Now American officials cheer on Myanmar’s government and vow to help it transform. Starting four years ago, khaki-suited dictators began shifting power to a parliament under their sway. Political prisoners were freed. Authorities allowed mobile phones to proliferate. Tourism exploded.

The nation hopes to earn the vaunted “democracy” label now that it’s passed the test of November elections, hyped as the first legit polls in half a century. The public delivered a landslide victory to a party helmed by Aung San Suu Kyi, a US-backed pro-democracy idol who hopes to scrub away the legacy of tyranny. Her camp is expected to take the reins in early 2016 and form a hybrid government with a clique of unelected military officers.

Hillary Clinton takes credit for expediting this makeover and touts it as a hallmark of her term as secretary of state. President Barack Obama, who has visited the nation twice in recent years, has focused on luring Myanmar away from China’s orbit and opening its long-closed markets to American corporations. He now praises the country’s “remarkable opportunity” to shift from despotism to something freer.

And it is getting freer, at least in the country’s tropical lowlands: a tourist-ready landscape of barefoot monks and golden pagodas.

But at the mountainous fringes, the nation is still plagued by warfare and the free flow of meth and heroin. And the government, riding high on Western praise, is quietly fanning the flames of this drug epidemic.

Exorcising the beast

“At times, [meth] brought me pleasure beyond compare,” says Maung Ring La, a 23-year-old from Kachin State entering his second week of sobriety. “But there is a dark side.”

After a four-year blur of heroin and meth abuse, Maung Ring La’s limbs are twiggy and his chest is shrunken. His head droops as if his confidence got sucked out through a vacuum.

He now spends his days inside a large cage at a rehab center in Myanmar’s northern city of Myitkyina. The wooden bars, he says, deter invasive thoughts of escaping to score drugs.

Maung Ring La is still reeling from his rock-bottom episode: a rampage through his parents’ home where he was scrounging for drug money.

“I broke every plate and glass in the kitchen. I even smashed the TV,” he says. “When my mother got home, she fainted. Without rehab, I knew the next step for an addict like me would be resorting to crime.”

Stories such as this abound in parts of Myanmar’s north where, as a local expression tells it, “drugs are sold like vegetables.”

Villages are strewn with dirty needles. Meth is available by motorbike delivery as early as dawn. Addicts loot unguarded homes of everything from motorbikes to sewing machines to damp jeans drying on clotheslines.

From this crisis emerges Patjasan, a legion of Christian anti-drug vigilantes armed with bamboo sticks. They assembled roughly two years ago and are credited with scaring many upland drug dealers back into the shadows.

Backed by tens of thousands of recruits, Patjasan is the largest organization within a growing phenomenon of ethnic minorities banding together to do what apathetic cops won’t: aggressively attack the drug trade. Even if that means home invasions, beatings and confiscating bundles of meth.

In the vigilantes’ eyes, it’s no coincidence that their rebellious homeland has been allowed to devolve into Asia’s top meth production zone.

Decades of brutal army attacks have failed to intimidate locals into accepting the government’s legitimacy. “That’s why they let drugs spread unchecked,” says Tu Raw, head of a 10,000-member Patjasan unit in Myitkyina.

“It’s obvious,” he says. “The government wants to weaken our ability to resist their rule.”

Patjasan has a much higher purpose than just smacking around addicts, Tu Raw says. It is preparing for a “revolutionary war” against the forces conspiring to turn the native population into worthless addicts. On his hit list: drug lords and the corrupt officials who give them shelter.

“They’re slowly torturing us to death with drugs,” Tu Raw says. “They’re getting rich from our pain.”

State-backed meth militias

When it comes to drugs, Myanmar is mired in a ridiculous paradox.

One wing of the government, the narcotics police, promises to transform Myanmar into a drug-free state. Yet a more powerful wing — the military — is secretly propping up militias that churn out massive quantities of heroin and meth.

The hidden link between these narco-militias and the government is confirmed by a long list of insiders from the US DEA, Thai police, Myanmar’s own anti-narcotics squads and the militias themselves.

Two types of military units are enmeshed in the drug trade. There are small factions called “people’s militia forces” that often wield fewer than a hundred troops. Larger and more disciplined factions, called “border guard forces,” control more than 300 personnel.

But they have a common purpose: expanding the government’s foothold in areas rife with rebel fighters.

“All of these ‘people’s militia forces’ are involved in the drug trade at some level,” says Whalen, who retired from the DEA in 2014 after a 26-year career spent mostly in Myanmar.

“It might be acquisition of methamphetamine precursors. It could be producing or tableting meth. Or maybe taxation and security,” Whalen says. “But all of these militias are intimately involved.”

State-backed militias, he says, are present at almost every link in the meth supply chain.

That long chain begins in neighboring India, where sinus medicine is purchased by the truckload. Sudafed-style pills contain pseudoephedrine: a key ingredient for cooking up meth.

Some militias are adept at smuggling cold pills through Myanmar to supply underground labs. Others have developed a more advanced skill: actually synthesizing pseudoephedrine into meth.

Some simply provide a secure sanctuary where outside syndicates can set up their own operations. “There are a bunch of different levels,” Whalen says, “and they’re involved at each stage.”

*****

For decades, America has condemned Myanmar for failing to seriously crack down on its homegrown drug lords.

But today, as the United States rekindles its friendship with Myanmar’s government, the White House is beginning to support its anti-narcotics forces outright.

The United States has begun offering limited financial support and training for the Central Committee for Drug Abuse Control or CCDAC, Myanmar’s answer to the DEA.

The nation’s reputation is so bleak that this decision required a special waiver, signed last year by President Obama.

This stark reversal is justified by a recent US State Department report. The document asserts that Myanmar’s drugs are primarily produced “in areas controlled by ethnic armed groups beyond the government of Burma’s immediate control.”

That line echoes Myanmar officials’ time-worn defense: the drug trade, they insist, is entirely the fault of anti-government rebels. But this pretense is transparently false.

In a rare interview with foreign media (or any media for that matter), a senior officer with Myanmar’s anti-narcotics agency reluctantly admits that government-backed militias are indeed active in the drug trade.

“We do believe some of them are involved in the drug business,” says Col. Myint Thein.

The colonel is unwilling to concede that state-sponsored militias are meth trade masterminds. Many, he says, are just providing an operations base for foreign drug syndicates, namely from China.

“Outside syndicates take advantage of our complex political situation by transporting and selling drugs,” Col. Myint Thein says. “The militias will often just tax the traffickers. The syndicates do most of the work.”

This is a staggering admission from one of Myanmar’s top narcotics officers — and one that complicates the government’s hopes of soaking up funds from the US, the United Nations and others.

Myanmar has requested more than $500 million in foreign funds to achieve an absurdly ambitious goal: eradicating all illegal drugs in the nation by 2019.

But when Western nations financially back Myanmar’s dubious anti-drug campaigns, they also engage with a government that offers its own militias carte blanche to inundate Asia’s streets with heroin and meth.

Vanilla haze

There is a hypnotic allure to the meth-smoking ritual, which plays out each morning in bamboo huts and posh condos across Southeast Asia.

Clad in a brown sarong, Samson sits cross-legged before a lit candle. Its flame is the centerpiece of his altar: a water bong built from a plastic bottle, foil strips and a whorl of interlinked, candy-colored drinking straws.

This session takes place around 10 a.m. inside a stuffy attic. Windows are shuttered, wives told to scram.

The city is Myitkyina, last stop on a northern railway line constructed during British colonial occupation. From above, it appears like a splotch of concrete on a sea of jade-green fields — an urban speck where motorbikes jostle for road space with roosters and half-naked kids.

This is the last outpost before Myanmar dissolves in a chaotic frontier.

Samson, 46, is the oldest of three meth smokers in the attic. (His name has been altered to prevent his arrest.) Two of the smokers are Christian, one is Muslim. All are stripped to the waist.

Samson unfurls a tightly wrapped baggie. Within seconds, the room fills with a toxic vanilla scent. This is the signature odor of “ya ma,” or “horse medicine” as it’s known in Myanmar. (In neighboring Thailand, it’s called “ya ba,” which means “crazy pills.”)

At Samson’s feet, there are 20-plus pills nestled in plastic wrapping. The little pink tablets will endow the men with a dazzling sense of self-satisfaction. They will feel as if they’ve just woken from glorious sleep, ready to seize a day electrified by grand possibility.

“These are 88s,” says Samson, gesturing to the pills. “They’re extra strong.” Stamped with the number “88,” the tablets are a relatively new brand on Myanmar’s meth scene. They are assumed to denote 1988.

That’s the year in which Aung San Suu Kyi, daughter of a beloved revolutionary general, led hundreds of thousands of protesters against the military junta.

For a moment, it seemed this uprising might force the generals to step down.

Instead, the army retaliated by slaughtering thousands in the streets.

Western nations recoiled in horror. They later dumped an avalanche of sanctions on the country, further deepening its poverty and isolation. Aung San Suu Kyi, who supported the sanctions, was anointed as a Mandela-style resistance hero and close confidante of the United States.

The year was burned into Myanmar’s collective spirit — apparently so much so that drug lords are still mining its appeal to brand their speed.

Samson pinches a strip of foil to create a little metallic canoe. He drops a pill inside and lovingly treats the underside of the aluminum with flame.

Fire makes the little pill dance. It shimmies around the foil, pouring smoke, slowly dissolving into a charred globule. All the while, meth fumes are pulled up into a straw plugged into the water bong.

Samson is on the other end, bent over, sucking so hard that the jade amulet looped around his neck jiggles.

Within minutes, the pill melts into a blackened squirt. Samson reloads the foil with fresh meth. His friend slides into position and the bong recommences to gurgling.

In another hour, the men will return to their job: repairing generators that keep the town humming through daily blackouts. But not before their mound of pills is depleted.

The pills are vanishing fast.

“This stuff gives you incredible alertness,” says Samson, still seated, sweat pooling in his belly folds. He seems unaware of the manic drum roll his fingers tap out on the splintery wooden floor. “You can become so focused on your work that you forget to eat.”

*****

Despite its depraved reputation, meth is seen as a productivity booster in much of hard-laboring Southeast Asia.

These men cook up pink pills for the same reason US grad students pop blue tabs of Adderall, a pharmaceutical-grade speed pill that powers America’s $9 billion prescription stimulant industry.

Even at the molecular level, the two uppers are extremely similar. Adderall is a cocktail of amphetamine salts. According to Carl Hart, a neuroscientist with Columbia University, “methamphetamine and Adderall are essentially the same drug.”

But if Adderall is Bombay Sapphire, meth is bathtub gin, whipped up by outlaws and sullied with cheap adulterants.

Both offer a euphoric blast of confidence and an intense curiosity in the mundane. Appetites evaporate. Daunting performance — 14-hour work days, marathon sex — becomes possible.

What follows is brutal exhaustion and, for those who overindulge, a sickly hollowed-out feeling. Long sessions leave meth smokers feeling like a husk of moist flesh. For heavy users, the impulse to keep scoring more is ferocious. Sleepless nights can bring on wild psychosis.

“You’ve got to stop and sleep at some point,” Samson says. “If you don’t regulate your meth intake, you’ll ruin your career. Your temper runs too hot. Your family falls apart.”

The men shrug at the mention of police who, according to Myanmar’s harsh drug laws, could imprison them for decades for possessing a pocketful of pills.

Bringing up Patjasan vigilantes, however, elicits a fearful shiver. “Yeah,” Samson says, “now that they’re out there, you’ve got to choose where you smoke more carefully.”

“Honestly, the real problem with smoking ya ma? You always think one more pill will bring perfect bliss,” Samson says. His co-workers, fidgety but clear-eyed, nod along. “That feeling never comes. It’s always one more pill away.”

The untouchables

Every narc detective in the borderlands knows who mass-produces all this pink speed. Even the DEA, from its office in Myanmar’s former capital, Yangon, can pinpoint meth refineries using heat signatures and satellites.

Raiding these labs, however, would spark full-on battles. The facilities are defended by armed brigades subservient to the groups that run them — either independence fighters or, increasingly, the militias created to extend state power into rebel lands.

“Going in there would be asking for a gun battle that we wouldn’t win,” says Maung Maung, an anti-narcotics police liaison in Kachin State. (His name has been altered to protect him from retribution.) “We’re just police. We’re not equipped for war.”

Myanmar’s local cops are woefully outgunned. The officers often pack antiquated carbines and rusty pistols — or no guns at all.

“I’ve even seen police take down low-level dealers with slingshots,” Maung Maung says. “How are we supposed to go against a militia with AK-47s and M16s?”

Busting meth labs run by militias under army protection is practically impossible. Narcotics police are forbidden from going after the army’s favored groups, even if their drug operations are blatant.

“When we catch small dealers, we start pumping them for information to find the bigger fish,” Maung Maung says. But when their trail leads to state-backed border forces — specifically units titled 1001, 1002 and 1003, all created by the army — “the questions stop and the investigation is over.”

*****

The army has effectively carved out no-go zones immune to the justice system. Even Col. Myint Thein, the senior narcotics officer, admits that prosecuting militias in “high mountains and dense jungles” is only possible with the military’s blessing.

“The army likes to keep the ‘people’s militia forces’ happy,” Whalen says. “They need them as force multipliers, guides, maybe cannon fodder. So they turn a blind eye to their activities.”

These state-backed militias have proliferated since 2009, the start of a divide-and-conquer operation to break off rebel brigades and woo them into siding with the army.

This strategy is a bit like the US military’s 2006 “Sunni Awakening” in Iraq, which co-opted formerly hostile militants to target rivals (like Al Qaeda) instead of American GIs. But where the United States bought loyalty with cash salaries, Myanmar does it with drug-trade concessions.

Ironically, this militia expansion campaign was mounted just before Myanmar’s much-hyped shift away from military rule. In total, the army created more than 35 new units backed by an estimated 10,000-plus fighters.

A typical example of these army creations: the Kaung-Kha militia, which holds turf near Ruili, China, a hotbed of teenage prostitutes and cheap meth.

“They are notorious traffickers,” Whalen says. He claims the DEA has intel on “a number of heroin and meth refineries” inside the militia’s terrain.

“But when we pass that information to police,” he says, “they go, ‘Yeah, you’re right. But we can’t do anything about it.’” US-gathered intel on drug shipments is often ignored, he says, when it implicates the army’s pet groups.

*****

Most narco-militias are cobbled together from troops bribed to defect from one of Myanmar’s 18-plus revolutionary guerrilla armies.

These turncoat militias then become “the eyes and ears of the army” in rebel terrain, says Khuensai Jaiyen, an expert on narcotics and armed groups in Myanmar.

Khuensai, now 67, gained an intimate knowledge of the drug trade while serving under Khun Sa, a drug kingpin on par with Colombia’s Pablo Escobar.

Khun Sa’s long career vacillated between resisting Myanmar’s military and, when convenient for his empire, cozying up to top officers. His high-grade heroin deluged New York City in the 1980s and '90s as the DEA actively sought his capture.

By the time he died of natural causes in 2007, with a US bounty of $2 million on his head, he was living lavishly in Yangon under government protection.

Myanmar’s new-era drug lords often make a similar business calculation. Cooperating with the government can prove much more lucrative than carving out a rebel fiefdom.

There are pros and cons to this arrangement, Khuensai says. The army offers only “token arms” and “no real” salary to allied militias. Nor does it offer much training or even proper military ranks.

“But they’ll say, ‘You can do anything you want in your area to support yourself,’” Khuensai says. “And that includes the drug trade.”

For state-backed militias, this impunity can provide a major edge over rebel drug producers, who remain vulnerable to army strikes and seizures. Outside financiers (namely Chinese mafia) prefer to cut deals with militiamen whose labs don’t get raided, Khuensai says.

“Investors love stability,” he says. “If you wanted to invest in a drug refinery, which place would you set up your operations?”

This license to traffic drugs, he says, has helped state-backed militias wrest away much of the trade from rebels.

“It’s not that [rebel] groups don’t produce a lot of drugs. They do,” Khuensai says. “But the ratio of drug production [between pro-government militias and rebels] must be about two to one.”

Little Escobars

If a drug lord shores up enough favor with Myanmar’s ruling elites, he is free to plunder like a Viking king. In fact, Myanmar’s generals did little to stop one of their own militia commanders from becoming Southeast Asia’s most brutal river pirate.

They barely flinched when Naw Kham, a Khun Sa protégé, conquered a key swath of the Mekong River near Thailand in the early 2000s. He amassed a battalion of killers, armed with M16s and RPGs, that racked up millions transporting meth and extorting cargo ships.

Naw Kham’s fatal mistake? Enraging the Chinese. In 2011, his crew shot and mutilated 13 Chinese sailors on cargo ships ferrying oil, apples and garlic. Their alleged offense: failing to pay protection money.

China’s government was so incensed that it embarked on a manhunt on foreign soil. They even pursued Naw Kham with a TNT-armed drone.

What would have been China’s first foray into US-style international drone assassination, however, was not to be. A China-led regional task force caught Naw Kham alive.

They dragged him to China and, in March 2013, executed him and aired his last moments on state TV. At 44, he left behind, according to Chinese authorities, an estimated $60 million operation.

This saga indicates the brutal extremes that Myanmar’s government will tolerate from its militia commanders.

In his final years, Naw Kham was ultimately disavowed by the army that gave rise to his wayward pirate clan. But for much of his reign, his connections emboldened him to extort, kidnap, traffic meth and murder.

If he hadn’t antagonized the world’s largest nation, he might still be terrorizing the Mekong today.

Naw Kham’s brutality is tough to match. But there are plenty of others like him in Myanmar: small-time Escobars, protected by the government, lording over their little fiefdoms.

“Smart drug traffickers like Naw Kham are careful to stay under the military umbrella,” says Win Oo, a recently retired senior narcotics agent in Myanmar. (His name has been altered to protect him from retribution.)

These narco-militia chiefs don’t have to seek out officers to bribe — the officers often come calling on their own, Win Oo says.

“It depends on their personality and their level of corruption. But many army battalion commanders want to befriend rich men,” he says. “Drug lords are the type of people they seek out for bribes.”

“In Myanmar, a colonel makes only $600 per month. Brigadier generals make just $900,” Win Oo says. “That’s why officers beg their superiors, ‘Please, send me to the border!’ That’s where they’ll find all the rich militias.”

Drug lords in office

Now that the army is shifting power to a parliament (albeit one stacked with its own officers), some narco-militia commanders have found a new way to fortify their impunity.

No fewer than 10 militia leaders have joined parliament in Myanmar in recent years — and at least one is a widely accused drug lord.

His name is Kyaw Myint and he was elected to Myanmar’s ruling party in 2010. His winning platform, according to researchers based in his precinct: tax-free poppy farming for five years.

His troops control turf near Muse, a rough city adjacent to China. “All the drug police know him,” Win Oo says. “He’s notorious.”

His militia isn’t just safeguarding territory for the government. It’s openly at war with a rebel faction: the Ta’ang National Liberation Army. The TNLA are sworn to protect their mountain-dwelling ethnic group, the Ta’ang, which is ravaged by addiction.

The rebels seek to drain their enemy’s wealth by capturing Kyaw Myint’s meth traffickers and hacking down his poppy fields. But according to Parn La, a senior TNLA officer, the rebels have paid for their defiance in dead recruits.

“As we see it, they’re producing drugs in our homeland,” Parn La says. “They must be stopped.”

The rebels see themselves as righteous freedom fighters protecting their tribe from drugs and government oppression. But they too are capable of harsh tactics.

Drug dealers caught by the TNLA are beaten and fined. Four-time offenders, Parn La says, can be shot dead. Incarceration is not an option. The rebels, constantly on the run, cannot maintain jungle prisons.

“We don’t want to be doing this,” Parn La says. “It’s a big distraction. We’re supposed to be using our troops to guard our native land. Instead, we’re in a drug war.”

Cross-border bloodshed

Skirmishes with state-backed drug militias aren’t confined to Myanmar. Violence routinely spills into Thailand, a country with a raging meth appetite and vast jungly borders. It is a traffickers’ paradise.

The militias usually send their smugglers across the border on foot, in groups of about 10, with backpacks full of pills and crystal meth, says Winyu Ponbrathum, commander of Thailand’s 327th Border Patrol Police.

“They’re very violent,” Winyu says. “They’re sent here by men who are basically mafia, men with powerful connections, producing vast amounts of meth.”

Thailand’s border police are better equipped to fend off militiamen than ragtag rebels such as the TNLA. They’re trained by the United States and tote M4 assault rifles donated by the American government. But they still struggle in firefights with militiamen willing to fight to the death.

“Militias don’t send smugglers here empty-handed,” Winyu says. “They’re bringing war weapons. Even grenades.”

Myanmar’s contemporary drug lords do not appear fazed by the capture of Naw Kham. In fact, an heir has already emerged. His name is Lt. Col. Yi Se, yet another commander within a “people’s militia force.”

According to Thai police, he manufactures meth pills stamped with the letters WY. The meaning is a mystery but to meth users, the brand is as recognizable as the Nike swoosh.

Thailand’s government offers a $138,000 bounty to anyone who can help bring Yi Se into custody. But privately, narc police lament that hopes of catching him are extremely low.

Myanmar’s authorities are not cooperating.

As one high-ranking Thai officer puts it: “Catching Yi Se? That’s about as easy as catching the perpetrators of 9/11.”

The invisible pillar

Myanmar — sucked dry for decades by its kleptocratic army — is starving for quality investment.

Washington, DC has depicted US corporations setting up shop in Myanmar as benevolent healers of a broken nation. Hillary Clinton has directly implored American firms to invest in Myanmar to “be an agent of positive change.”

But what the White House and other pro-investment cheerleaders seldom mention is that the economy here is warped by drugs.

On paper, Myanmar’s top exports are natural gas and jade, as well as beans and seeds. But the beans are a joke compared to meth and heroin, known to be among Myanmar’s most lucrative exports.

Trying to size up this invisible economic pillar is maddening. A US congressional study pegs Myanmar’s drug exports at $1 billion to $2 billion. That’s within range of the country’s natural gas exports, which are valued at $3.3 billion and, according to officials, bring in roughly 40 percent of the poor nation’s income.

But the drug export estimates are flimsy. No one can honestly claim to know how much meth is produced in Myanmar. Not the government. Not even the scattered drug syndicates.

Heroin production can be estimated by analyzing poppy fields from satellites. But meth is far less traceable. It is synthesized inside huts and hidden factories that look completely unremarkable from space.

DEA agents calculate meth output, Whalen says, by adding up regional seizures “and making a wild-ass guess that it represents between 1 and 10 percent of production.”

Since 2009, when the army brought dozens of new militias to life, meth seizures in Asia have increased by a factor of 10. Authorities seized a whopping 270 million meth pills across the region last year, up from 24 million in 2008. Feed the up-to-date figures on seizures into the DEA’s algorithm and you’re looking at a conservative estimate of 2.7 billion meth tablets produced in Asia.

Officials with the UN’s Office on Drugs and Crime assume that Myanmar alone is pumping out one to two billion of those pills.

The fortunes reaped from meth, Whalen says, are supplying seed capital to industries that flourish in Myanmar’s post-sanctions era. The former agent sees drug money behind the boom of shopping malls and hotels rising across Yangon, its largest city.

“They’ve got to do something with that money,” Whalen says. “They’ve got to turn their money from black to white.”

With all that drug money sloshing around, visitors to Myanmar find it almost impossible to avoid brushing up against the proceeds.

That even goes for the president of the United States, a nation that spent decades issuing sanctions to drain the fortunes of junta tyrants and drug lords.

On Obama’s latest Myanmar visit, he slept in the Kempinski Hotel, co-owned by the firm Jewellery Luck, which was caught six years ago trying to ship heroin bricks to Taiwan.

Return to the quagmire

The Myanmar government’s collusion with narco-militias should come as no surprise to the United States.

In 2008, before the two nations rekindled their friendship, US State Department documents called drug trafficking a “low-risk enterprise” in Myanmar. Their rationale: corrupt officials offer “the criminal underground immunity from law enforcement.”

But that accusatory rhetoric has softened. The latest US campaign is seeking influence over all arenas in the country, from the economy to parliament — and it includes expanding its global drug war into Myanmar.

The White House still states that Myanmar has “failed demonstrably” to combat the drug trade. But documents signed by Obama also contend that aiding Myanmar’s narc police is now “vital to the national interests of the United States.”

Narco-militias are indeed bad for America’s prime policy goal in Myanmar: free and fair elections. In some places run by drug lords, citizens weren’t allowed to vote in November’s historic polls.

This isn’t entirely the government’s fault. One of the world’s largest meth producers, the United Wa State Army, essentially runs an independent state within Myanmar. Armed with high-grade Chinese weapons, the group has enough firepower to tell the government to take its election and shove it.

*****

As America wades into this drug-infused political scene, it is treading old ground that is steeped in scandal.

Through most of the 1970s and 1980s, America was the No. 1 foreign financier of Myanmar’s counter-narcotics campaigns. Over 15 years, the United States provided $80 million along with dozens of helicopters and planes.

The aircraft were supposed to help survey and eradicate poppy fields.

Instead, they were deployed to the front lines of grisly jungle wars.

According to a former US defense attache in Myanmar, the junta used American choppers and planes in the brutal suppression of ethnic-minority guerrilla factions — some of which had no ties to the drug trade.

This relationship finally imploded in 1988, when the junta brazenly slaughtered pro-democracy protesters led by Aung San Suu Kyi.

Though inured to Myanmar’s dysfunction, Whalen, the ex-DEA agent, still believes the United States should buoy Myanmar’s small strain of uncorrupted officers. Many narc police, he says, are sincere cops who enjoy the prestige of working cases alongside US agents.

“You can slowly effect change,” he says. “It might take 30 years. But if you have no engagement, you have no hope of that at all.”

Vigilante bravado

The earnings forecast for state-backed militias looks fantastic. Their top product, meth, is a hit among Asia’s hard laborers and party kids alike.

In the clubs of Bangkok and Phnom Penh, the drug destroys inhibition and offers a night of oversexed, jaw-grinding bliss. In Yunan and Ho Chi Minh City, it alleviates drudgery for factory workers assembling cheap goods for America’s superstores.

There is just one threat, however dim, emerging on the horizon.

That would be Patjasan.

Early victories, such as chasing dealers out of drug-plagued neighborhoods, are inspiring a reckless confidence. Some bolder vigilante crews are now ready to confront the government’s narco-brigades directly.

Late last year, the group deployed hundreds of stick-wielding villagers into poppy fields controlled by a state-backed militia in Kachin State. As they began to hack down the stalks, bullets whizzed over their heads. The group scattered into the hills.

“If we’d proceeded,” says Tu Raw, the stony faced and bespectacled Patajasan leader, “we would’ve been shot down by the militia.”

“They have guns and we do not,” he says. “But we are determined to continue infiltrating their area.”

Compared to its early days in 2013, the organization has evolved. Enforcers no longer simply whip suspected users and turn them loose. Patjasan now guides addicts to jungle rehab camps run by churches.

By Western standards, the camps are rough. Users often show up with bruises dealt out by Patjasan. Most are locked in room-sized cages during withdrawal to prevent escapes.

But those who cooperate, agreeing to a regimen of chores and gospel sing-alongs, are treated kindly and nourished back to health.

Better still, this treatment is free of charge. Most camps are run on the cheap by altruistic evangelists who rely on community donations. The price of one week’s stay at a deluxe Los Angeles rehab could likely support one of these jungle rehabs for a year.

La Seng, the jobless man snatched from his shack, was not placed into a rehab cell. He spent three days inside a church’s wooden outbuilding, a discreet place hidden down a gravel road a mile or so from the chapel.

Though fed well by churchgoing aunties, he was forced to sleep with his feet in stocks. Each night, he lay awake wondering why he was careless enough to toss that meth bong where Patjasan’s raiders could find it.

Wobbly on his feet after days in detention, he is finally set free. Patjasan’s verdict: La Seng’s drug habit is too mild for the rehab camps. “But they have their eye on me,” he says. “They told me that next time my punishment will be much more severe.”

*****

Unsatisfied with merely chasing down addicts — and unable to take down militias — the Patjasan vigilantes are ramping up another dangerous tactic. They’ve started raiding dealers’ stash houses and seizing bundles of meth and heroin.

So far, Tu Raw claims they’ve confiscated more than 100,000 meth pills. All drugs, he says, are turned over to police — a move to humiliate the government for its inaction.

Tu Raw comes off as a serious man, a stern uncle who relishes his vigilantes’ no-nonsense image. But he turns giddily proud as he fishes a mobile phone from his plaid sarong and dials up a video clip.

Shaky smartphone footage shows a uniformed cop, looking sheepish, surrounded by hostile men. In the background, there are leafy plants and shacks made of tin sheeting: telltale features of a downtrodden village.

“We caught this cop dealing drugs,” Tu Raw says. Then comes the clip’s climax: a guy in a red tank top emerging to — thwack! — slap the cop across the face.

Tu Raw cracks a grin. “Our next steps hinge on the government. They can start suppressing the drug trade if they want,” he says. “But if not, we will fight this genocide by any means necessary.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!