Jason Torres and Daniel Fienco, "I Was There" participants, line up a shot for their film "What's Really Important"

Imagine growing up as the son of a famous general, the grandson of an even more famous one, with seven generations of West Point graduates on both sides of your family. The answer to "What should I do with my life?" seems like a foregone conclusion.

“I initially interpreted it as my father being disappointed if I didn’t go in the military,” says Benjamin Patton. Yes, that Patton. His father was George S. Patton IV, a decorated Vietnam War general. His grandfather you know from World War II and movie fame.

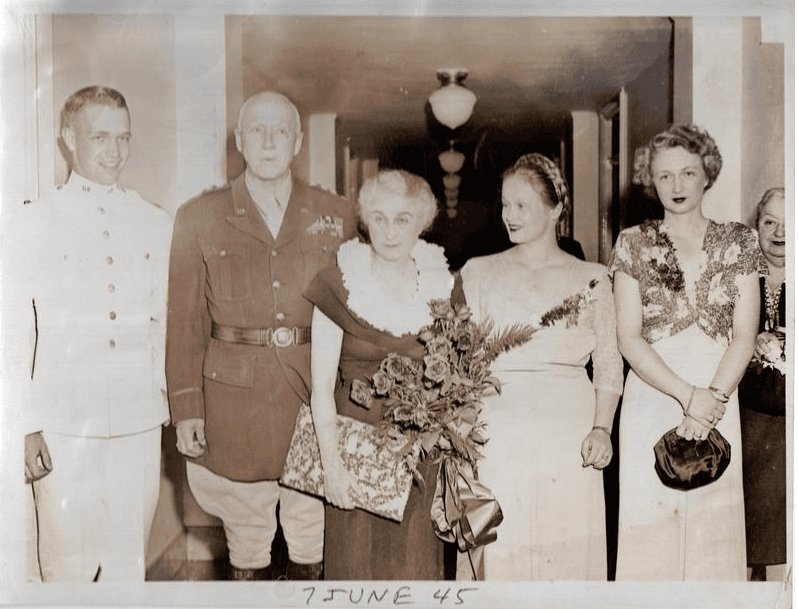

_1.png&w=1920&q=75)

“But I think it was more that history was pressuring me," he says. "I ultimately chose a different path.”

That path involved spending a year working as a blacksmith and farmer at a Benedictine abbey and working as producer for public television. He also taught teenagers how to make their own films, an experience that unexpectedly led him back to the military world three years ago.

That's when Patton founded “I Was There,” a non-profit that teaches veterans how to make films — together. “You have a lot of veterans that feel very isolated — from their families, from their battle buddies, from their therapists — from anyone they interact with, and that sort of feeds on itself,” he says.

Some are struggling with post-traumatic stress after seeing combat in Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam or Korea; others are dealing with the normal anxieties of re-entering civilian life, whether professional, financial, marital or otherwise; but all of them are figuring out how to tell their own stories, and Patton figured filmmaking could serve as a form of therapy — without calling it that.

“[The veterans] just think it’s not cool," he says. "It’s not macho, it’s not tough to go and cry in front of your therapist or talk about something that happened to you."

Filmmaking gives them the opportunity to approach their experience from a different angle by, say, using GI Joe dolls as stand-ins for themselves, or by making smart use of satire. That's what Alex Brandt and Jamie Brown did in their comedy “Red Tape,” which takes place at Virginia's Fort Belvoir.

"Basically, it was a film about all the different things they have to file in triplicate to even get a pencil," Patton says. "By the end of the film, [the soldier] has gone back again and again and again to the duty officer asking how to get this pencil and file this form and that. And every time he goes back, he has more and more red masking tape around his body. … At the end of the film he’s absolutely wrapped up and can’t actually move.”

Other students have made films about suicide prevention and PTSD or created moving personal accounts about coping with trauma. So does Ben think the members of his own family suffered from PTSD? After all, the term wasn't even used until the 1970s.

“I think they themselves would not say that they had post-traumatic stress,” Ben says of his father and grandfather. "But I’ve met enough veterans that when I ask them about it they say, 'Look, Ben, it’s just a matter of degrees and we all have it to some extent. And if you’re not willing to admit it, you’re a fool.'"

It's a particularly interesting case for Patton's grandfather, nicknamed "Old Blood and Guts," who considered what was then thought of as "battle fatigue" as mere cowardice. Patton, Jr. famously struck a couple of mentally wounded soldiers in the summer of 1943 during the invasion of Sicily, an act that nearly ended his career.

"That cost him his job, and frankly cost him the command of the Normandy invasion — and almost took him out of the war entirely," Patton says.

On the surface, it doesn’t seem like Ben has much in common with his grandfather. But the more Patton talks about his family — he's written a book about them, called "Growing Up Patton" — the more parallels I see. For one, his father and grandfather were both great raconteurs and filmmakers; both logged hundreds of hours of home-movie footage. But there’s also something attitudinal — this feeling of duty, almost devotion, Patton has for veterans.

“They appreciate that you’re paying attention because they kind of expect that you’re not," he says. "So it’s a nice surprise when you say, 'I saw you in that film and I thought you acted really well.'" And after each "I Was There" workshop, he makes a personal phone call to every participant. That’s 500 veterans so far.

He may have never enlisted, but he's proved there are more ways than one to uphold a legacy.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?