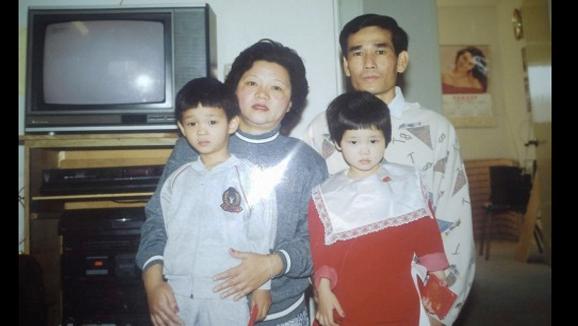

A photo of Tam Duong's family during Lunar New Year in the early 1990s. Tam, on the right in the red dress, is from Los Angeles and now lives in Boston. Her parents are from Vietnam and Duong says she was confused as to why Santa never came to their home.

Every year the same question crops up to a growing handful of us who are the children of non-Judeo-Christian immigrants: "Do you celebrate Christmas?"

It's a tricky question. Christmas is unavoidable and usually less about Jesus's birthday than the fact that many of us have days off and a hankering for hot cocoa and Bing Crosby.

Yet co-workers, friends and teachers tread lightly around us, hesitant to send us Christmas cards or hand us a candy cane. They safely wish us a "Happy Holiday" rather than the usual "Merry Christmas."

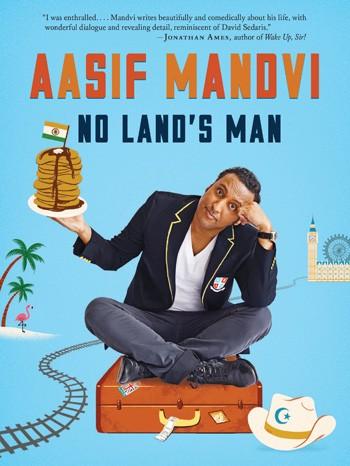

In his new book, "No Land's Man: A Perilous Journey through Romance, Islam, and Brunch," comedian Aasif Mandvi talks about his fish-out-of-water experiences with the holiday. He grew up in an Indian Muslim household in the UK and then moved to Florida as a teenager.

And Christmas celebrations on two different continents brought their own surprises for The Daily Show correspondent.

"I don’t think my parents really knew how to celebrate Christmas when we first got to the UK," he says. The holiday was mostly about giving each other gifts, but there was a logistical problem. "We didn’t have a Christmas tree for like the first ten years … my parents would just hide gifts behind the sofa."

As for the religious angle, the birth of Jesus Christ, "[My parents] kind of rationalized this … like, 'Jesus is in the Koran, so probably it's okay to celebrate his birth'"

After the family relocated to Florida, Mandvi says he realized Christmas was "on steroids" in the US. But his family still kept with tradition, even when wallets were thin.

"When we first came to America, my parents didn’t have a lot of money and they were sort of struggling for a while," he says. "That first Christmas they couldn’t really buy us a lot of gifts. This sounds very sort of Dickensian, but my dad got us each one gift. And then, in order to pad it out, he wrapped other things in Christmas wrapping."

One of the randomly wrapped items was a bottle of Planter's peanuts. "It was a little bit of a joke, but … also because they didn’t really have a lot," Mandvi says, "So now, in our home, every year one of the gifts is a wrapped up bottle of Planter’s peanuts."

At the other end of the spectrum, Tam Duong's family simply didn't do Christmas at all.

The 27-year-old attended elementary school in Los Angles and lived in a mostly Latino neighborhood. She learned about Santa, Rudolph and the Three Wise Men at school and came home to consult her Vietnamese Buddhist parents.

"When I came home and tried to talk to my family about [Christmas] they had no idea what I was talking about," she says. "They said it was just a holiday for Americans and we’re a Vietnamese family and Vietnamese people don’t usually celebrate Christmas."

But Duong, who now lives in Boston, says she was persistent. "I did write letters to Santa, I just never got a response," she remembers. "When I was little, I used to put out cookies and milk thinking that Santa would come and that [gesture] would bring me presents, but Santa never came and my mom would get angry because she said leaving out cookies like that will attract ants."

Growing up in a country that celebrates Christmas rather than the lunar New Year, Eid or Diwali means that immigrants families adjust their rhythms. If nothing else, major non-Christian holidays don't mesh well with the standard US federal calendar. And while there's a push to get public schools to recognize Eid in some states, it's still rare.

Manvi says when he wasn't with his family during the Muslim holiday of Eid, he didn't really celebrate much. "Eid is something that, for many years, my parents would call and be like, ‘Hey, it’s Eid tomorrow,'" he says. "I would celebrate just by virtually a phone call."

And Duong says that while some teachers allowed her to take time off to celebrate the lunar New Year, the make up work was a hassle. "I think schools could do a better job of acknowledging that their student population is diverse and not to assume that everyone celebrates Christmas," she says,.

The good news is that Christmas can be a learning experience. My own family embraced — and embellishes — the holiday, even after my sister and I came home from school with stories about a jolly, obese man who breaks into your home with good intentions. One Christmas, my father even dusted the bottom of his shoes with baby powder and marched around our living room carpet, leaving us all bewildered by the odd-smelling evidence.

"I think [my parents] want to celebrate Christmas, but they don’t know how," Duong says, "So they wait for [me and my fiancé] to come home and do something with them. We just cook a big dinner, and we’ll buy them little gifts and try to bring Christmas to them in a way."

In a way, our immigrant parents learn more about the US when we inundate them with candy canes and carols. So, at least until we get a week off for fireworks on Diwali, we'll make the most of our time off on Christmas.

A previous version of this story misspelled Tam Duong's name.

What about you? What traditions have you created with your immigrant family? Tell us in the comments below!

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?