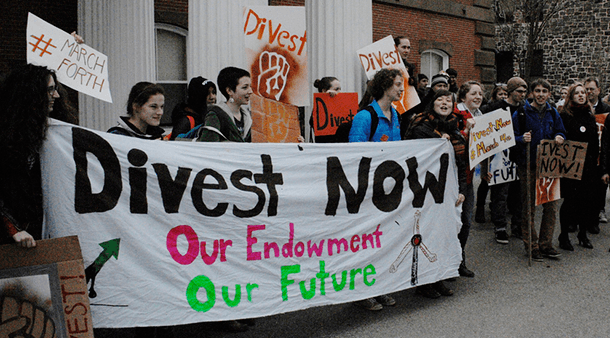

Harvard students increase the pressure on their administration to divest from fossil fuels

Students and faculty from more than 500 universities around the globe are pushing their administrations to divest endowments from holdings in fossil fuel companies. But so far, only a handful have committed to divestment.

Students at Harvard, frustrated by the university’s refusal to divest its endowment from fossil fuels, are taking the Harvard University Corporation to court.

The complaint charges “mismanagement of charitable funds” and “intentional investment in abnormally dangerous activities.” It was filed in state court on behalf of seven students and “future generations.”

The legal claim is unusual and it is not clear whether a judge would even agree the students have standing to bring the suit. Nevertheless, divestment proponents are hoping it will put additional pressure on Harvard and other universities to take the issue more seriously.

Globally, there are almost 500 university movements to divest, notes legal scholar and commentator Evan Mandery, yet the movement has gained no traction with university presidents and trustees. “There’s really a gross disconnect between what these boards of trustees are saying and what the actual university communities are saying,” Mandery says.

Mandery, a law professor at City University of New York, is a graduate of Harvard Law School. He recently wrote a long opinion piece in The New York Times about the resistance to divestment of Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust and hundreds of other college trustees.

“I read the president's letter, in which she says that the school has no ethical obligation, that it should maximize its return on endowment resources and use those to support the academic mission,” Mandery says. “In President Faust’s words, endowment assets are ‘not an instrument to propel social change’ — and I'm just shocked by that.”

In fact, Mandery thinks Gilpin and other university presidents don’t really buy their own argument. “We can all easily envision investments that universities [might] make that no one would tolerate,” he says. “If Harvard had money invested in a company that profited by using child labor, there isn't a single person who would think that was defensible, just because Harvard was generating a greater return on its endowment or using that money to support financial aid.”

Mandery believes the resistance to divestment “has to do with the fact that trustees are making the decision as opposed to it being a university community-wide decision.”

“The trustees aren't exactly a representative cross-section of the university,” he says, noting that trustees are disproportionately from financial industries. He suggests that divestment “feels like a repudiation of what the trustees have done with their lives.”

In his New York Times piece, Mandery acknowledges “divestment is a slippery slope.” “Where do universities draw the line?” he writes. “Columbia’s president, Lee C. Bollinger, says, ‘The bar has to be very high, and the reason is there are lots of things that people don’t like about the world.’”

But this doesn't free them from the responsibility of “listening to the distinction students and faculty have drawn between driving corporations out of business and changing their behavior," Mandery insists.

None of the university presidents doubt the science on climate change, Mandery believes. “Many of them, in their letters refusing to divest, say they accept the science … and view [investment in fossil fuels] as ethically problematic. They just don't see divestment as a way to address it,” he says.

But universities “grossly underestimate the symbolic importance [they] play in setting the tone for moral debate,” Mandery contends. And he believes divestment is inevitable.

“The only question,” he says, “is whether they'll divest at a point when it'll actually lead to some good happening more quickly than it otherwise would have, or whether it'll just be a purely symbolic statement — just because it would be a public relations nightmare if they fail to do so.”

This story is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.