Burkina Faso’s protests broke 27 years of fear and silence

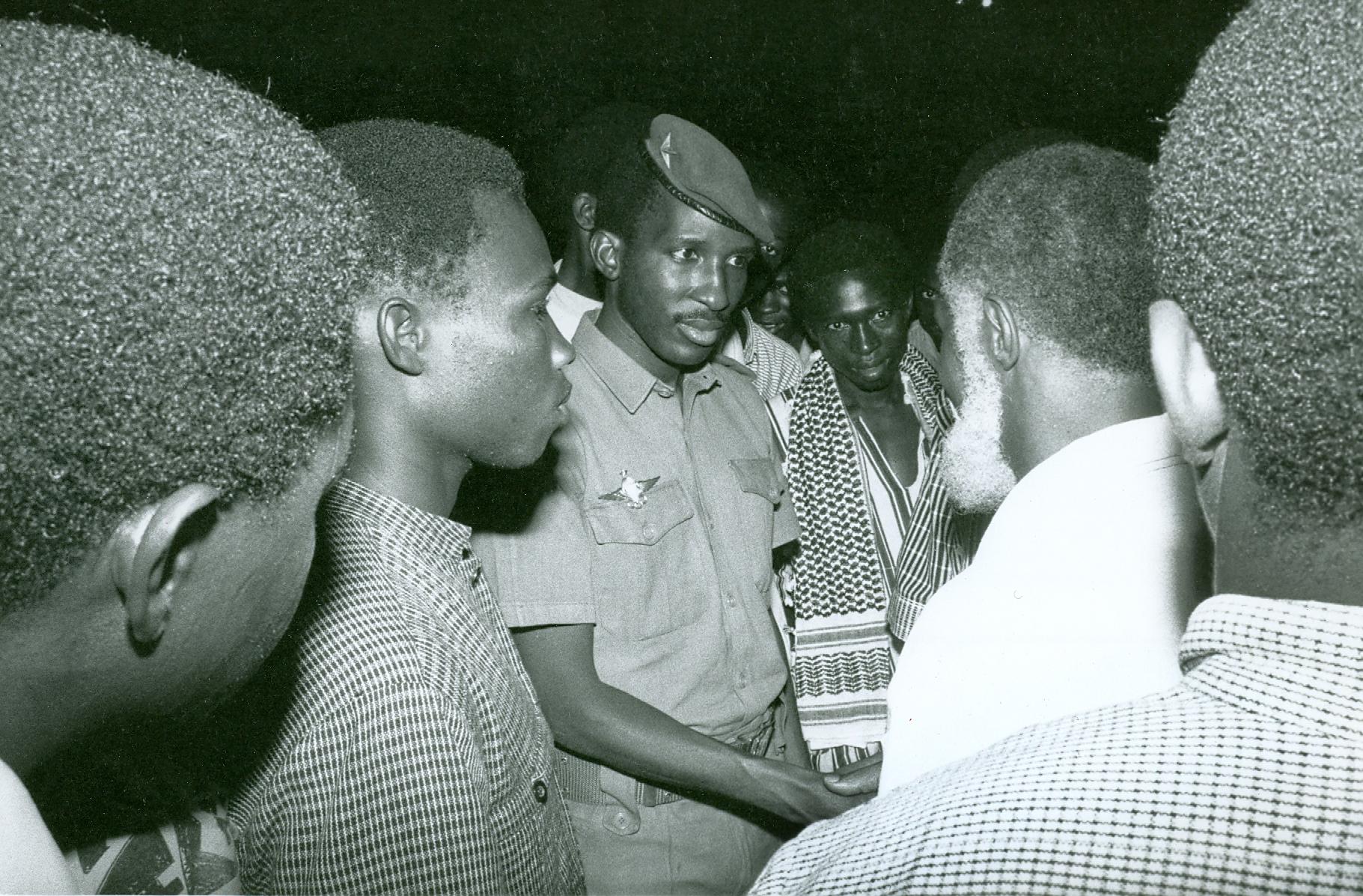

Thomas Sankara greeting attendees at Burkina Faso's Anti-Apartheid Conference in 1987, one of his last official functions before he was assassinated.

Big news unfolded in West Africa last week: Burkina Faso's president, Blaise Compaoré, resigned after 27 years in office.

Compaoré was one of Africa longest-serving heads of state, but his attempt to change the constitution and hold onto power for another three terms and 15 years sparked huge protests that turned violent last week. Now the military is in charge — they say temporarily — and protests have continued against their seizure of power, too.

And while "Ouagadougou" might be an answer to a $500 question on Jeopardy! for most people — "What is the capital of the former Republic of Upper Volta?" — this is a personal story to me.

Sankara was a feminist who appointed many women as government ministers; he played electric guitar; he was a lover of cinema; he was witty and charismatic. But more than anything, he wanted his people — and all Africans — to understand they were the masters of their own destiny, not pawns of outside countries or companies.

Some critics said his brand of neo-socialism was out of step with the desires of his people to be more like the west. Sankara would reply that if they wanted to eat Brie, there was great cheese in Burkina made by Fulani shepherds.

The same went for clothing: Burkinabe government employees used to wear suits to work, but Sankara insisted that if you worked for the government, you had to wear locally grown and woven cotton.

It was all summed up in a single phrase: Produce what we consume, and consume what we produce. Those words were on a billboard not far from my home in the center of Ouagadougou.

And while it was a radical agenda, Sankara's economic mission statement remains solid today as a blueprint for much of Africa. And of course, the buy-local movement has taken off in the West now.

But all of this didn't last long. A month after I arrived, Blaise Compaoré — then the second-in-command — organized a coup against Sankara, his friend and leader.

Burkina Faso had already lived through several coups since gaining independence in 1958. But the one that brought down Thomas Sankara in the middle of a presidential meeting in October of 1987 was bloody and violent: A grenade was tossed into the room, flushing its occupants outside — where they were mowed down by machine-gun fire.

Burkinabe were freaked out. They dared not speak out against this new menacing force, Blaise Compaoré, a man they thought they knew. I stayed in Ouagadougou for two years, waiting for people to rise up, or speak out publicly. It never happened.

But in the days after the coup in 1987, some brave soul at the national radio station strayed from the mandated playlist of military music, and spun this song:

oembed://http%3A//youtu.be/8VCuCm6XKeA

You don't expect to hear Dionne Warwick in the middle of a coup. The message: Compaoré, you killed Sankara and you broke our hearts.

Now, 27 years later, Burkinabe finally spoke out, and they didn't need a code to let Blaise Compaoré know how they felt.