The latest news on the ozone layer shows we can solve big environmental problems

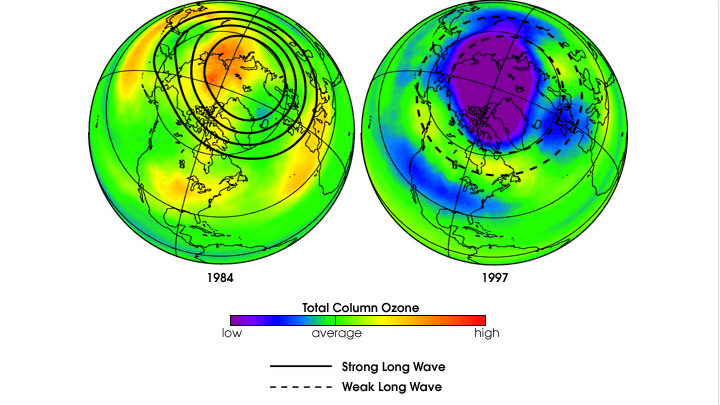

This NASA graphic shows relative average levels of atmospheric ozone over the northern hemisphere in 1984 and 1997. The lower concentrations, shown in darker colors, are due to the effects of ozone-destroying chemicals in the atmosphere.

Here’s a rare thing these day: Two pieces of good news on the environment in just one week.

A few days ago, we reported on how the population of blue whales in the eastern Pacific has bounced back to nearly where it was before whaling. Now there's news that the ozone layer is making a comeback of its own.

Remember ozone? You’re forgiven if you don't, since the issue has mostly been out of the public eye for years. That's because we actually figured out a solution to it 25 years ago. This latest news confirms that the solution is finally starting to pay off.

Here's a little history: Back in the 1970s, Mario Molina at MIT and Sherry Roland at the University of California-Irvine discovered that CFCs — common chemicals that were used in refrigeration and air-conditioning — were escaping into the atmosphere and destroying the earth's ozone layer.

Ozone is a special and very fragile kind of oxygen — O3. There's not much of it in the atmosphere, but the little bit that does exist helps make life on earth possible. It filters out some of the powerful ultraviolet rays from the sun that can otherwise harm DNA and cause maladies like skin cancer.

Things went from problem to solution with surprising speed — as far as these things go, anyway. The scientists realized CFCs could destroy the ozone layer — and were eventually rewarded with a Nobel Prize — and their findings were quickly followed by clear evidence of ozone depletion. Within a little more than a decade, nations signed a global agreement to phase those chemicals out.

That agreement, called the Montreal Protocol, went into effect in 1989. Now, 25 years later, the UN Environment Program and the World Meteorological Organization report that ozone levels have finally stopped falling. In some parts of the atmosphere, they've actually started increasing.

So how is this good news if it’s taken 25 years for the ozone layer to even begin to bounce back?

The reason for the lag is that it takes a long time for the ozone-destroying chemicals we put in the atmosphere to do their dirty work. That means it takes a similarly long time for the ozone — which is constantly being created by solar radiation — to build back up again. It’s a slow process, but the concentration of CFCs is going down and the concentration of ozone is going up, so by mid-century it’ll be roughly back to normal levels in much of the atmosphere.

This doesn’t mean we’re totally out of the woods on the ozone problem. It’ll still be several more decades before the protective shield is near normal again. There are also some new ozone-eating chemicals out there, as well as a complicated interplay between ozone levels and the pollution and processes involved in climate change.

But the bottom line is this: Ozone is a big, global, environmental success story, in a whole lot of ways. Scientists identified the problem; governments all over the world came together on a plan to fix it; industry figured out how to replace those chemicals; and now all that effort is paying off, which will make a big difference to the health of people, animals and plants around the world.

One of the big ironies in this, of course, is that early on in that process, industry protested that the science was uncertain and that it would cost too much to replace the chemicals. Sound familiar? It is the same fight playing out in today’s debate over climate change. Only the stakes with climate change are even higher, the consequences even more grave, and the economic and technological challenges vastly greater.

So the lesson of the ozone story is that we can tackle these problems. The Montreal protocol is the model of international cooperation on global environmental issues. And the new report makes clear it is working.

Often, the news on the environment is downright grim and that can take an emotional toll on just about all of us. It’s important to be reminded that when we really put our minds to it, we can actually fix a lot of the environmental problems we’ve created for ourselves.

The ozone story is a great example of that, and a moment to take heart about the future.