Scientists are racing to perform human trials on a possible cure and vaccine for Ebola

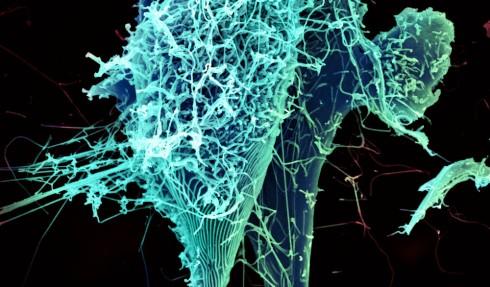

An electron microscope image of the string-like Ebola virus. Scientists at the NIH are working quickly on a drug and vaccine they hope will halt the spread of Ebola.

When two American aid workers stricken with Ebola were given an experimental treatment called ZMapp, both were seemingly cured. But a big question remained: Did the drug itself cure them or might they have recovered just the same without it?

Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, had this to say at a Congressional hearing this month:

You might have seen a lot of press converage about experimental treatment, and the plain fact is that we don’t know whether that treatment is helpful, harmful or doesn't have any impact. And we're unlikely to know from the experience of two or a handful of patients whether it works.

Prior to its use on the two Americans, ZMapp had only ever been tested in monkeys. But the results of those tests were remarkable: ZMapp apparently cured Ebola in all 18 monkeys, even when it was given to some of them five days after being infected with the disease.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases — part of the National Institutes of Heatlh (NIH) in Bethesda, Md. — says the results of the animal study are convincing. So convincing, in fact, that he thinks ZMapp is ready to go to a Phase I clinical trial in humans.

“Sometimes something looks good in animals, but it’s not particularly safe in the human,” Fauci says. “You can [test for] that pretty quickly."

But there's one significant obstacle standing in the way of a human clinical trial. There are no doses of ZMapp left. Producing the drug is a slow process, Fauci says, so it’s going to take another couple of months to create a modest number of doses.

“The company is trying right now to figure out a way to scale it up so that you could have many, many more doses much more efficienly,” Fauci says. “[Once] it is made, a clinical trial will have to be done as expeditiously as possible. Because if it does work in humans, you certainly want to get it to the people who need it as soon as possible — but you have to prove that it works, and that it’s safe.”

In addition to ZMapp, an Ebola vaccine has just started Phase I clinical trials in humans. Like ZMapp, Fauci says the vaccine looked very promising in a study using monkeys.

Researchers at the NIH have started testing the vaccine on 20 normal, healthy volunteers between the ages of 18 and 50. “Safety is the paramount issue that we're looking at,” Fauci says, “to make sure that we don’t have any unexpected reactions to this particular vaccine.”

Even when researchers feel they are in a race against time, testing a vaccine is a painstaking process. The testing protocol requires administering the drug to three people, then waiting to make sure everything is okay, and then moving on to the next three people — all while gradually raising the dosage.

“You've got to do it very carefully in a step-by-step fashion," Fauci explains, "to make sure that you don’t give it to twenty people all at once and then you find out all 20 of them have some sort of adverse reaction."

Fauci emphasizes that the vaccine has “absolutely no chance of giving Ebola to anyone — because it isn't the Ebola virus" that's in the shot. The vaccine contains only a very small segment of the virus' genetic material. That segment codes for an important protein researchers hope will produce an immune system response in humans. Further tests will be done in Britain, Mali and Gambia.

“When I say we're talking safety, we're talking about any adverse reaction to the vaccine, such as swelling, or a hypersensitivity reaction or any sort of unexpected reaction,” Facui says.

If the vaccine proves effective, doctors will first target the people who are at the highest risk, namely the first responders and health care providers who are caring for the sick.

Fauci says researchers are benefitting greatly from biomedical technologies developed in the past 15 to 20 years, especially the ability to do “extraordinarily rapid and sensitive and deep [genetic] sequencing.”

For example, he says, "a molecular virologist from the Broad Institute and other collaborators were able to sequence the species of Ebola from 78 individuals … and they were literally able to show a road map of how the virus evolved."

That work led scientists to "Patient Zero" of the current outbreak, he notes. “They proved that it came from a woman who had gone to a funeral and had touched the body of an individual, and that was the point source of the outbreak.”

That, Fauci says, is excellent news for the future. “We know so much more about how these viruses spread now than we knew 10 to 15 years ago.”

This story is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Science Friday with Ira Flatow.

(Editor's note: This story was updated to indicate that vaccine tests have already started in the US and are planned for the UK, Mali and Gambia.)

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?