The long-extinct passenger pigeon might get the Jurassic Park treatment

Passenger pigeons went extinct decades ago, now scientists are on the verge of bringing them back.

Everybody loves a comeback, right? Well, science might have the craziest comeback story yet. Scientists are working on a way to make the once-abundant passenger pigeon de-extinct.

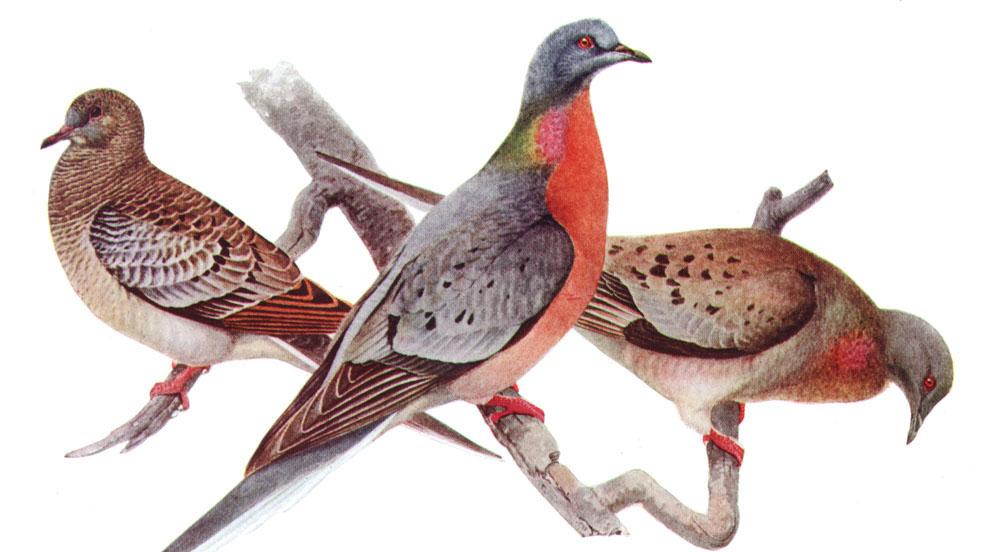

Passenger pigeons were once the most common verterbrates in North America. The bird died out 100 years ago, but collectors and scientists left behind lots of specimens, tissue samples and extensive records.

Thanks to those leftover samples, the passenger pigeon is ripe for for de-extinction. That's a process of editing and replacing genomes that scientists are trying to develop.

"'Combining' is the best way to say it," says Ben Novak, lead scientist for The Great Passenger Pigeon Comeback. It's a program of Revive & Restore, a non-profit that supports biodiversity. "We take a tiny bit of tissue and extract the DNA fragments from it — which can be very small, old and degraded over time — and we decipher what the genetic code once was."

That may sound farfetched, but Novak says he and his team "are actually able to sequence nearly the entire genome of a passenger pigeon and really finitely engineer code." For readers who may be having unwelcome Jurassic Park flashbacks, that means there's no need to take DNA from other species to fill in the code.

But once that code is complete, the scientists still need a way to hatch the pigeon. "The limitation is the cloning step," Novak admits.

For that, they're using a process called germline transmission. Germlines "are a type of cell that will become the sperm and egg," Novak explains. "They can take those from one bird and pass them through a separate host bird" — in other words, reprogram the sperm and eggs inside of one species to produce a different species.

It's been done before — Novak points out a case where transmission was performed with a duck: "So this duck, this living male duck, has the sperm of a chicken and breeds chickens." And that's the plan for the passenger pigeons: Novak's team hopes to put passenger pigeon sperm and eggs inside band-tailed pigeons, the passenger's closest extant relatives.

Then, voila! Passenger pigeons for the first time in a century. Novak admits it's a cool technological tale — his group is based in Silicon Valley — but says, "the essence of this project is the conversation, the idea that the wood pigeon of the east has been missing for 100 years and we'd like to restore that ecological role."

And then there's the real issue: What to call the first new pigeon that pops out. Novak says people have been calling the hypothetical chick Passenger Pigeon 2.0, but he admits that's awful. "The first one really needs kind of a great name," he says. "I think maybe we should have a national … vote for ideas."

This story first aired as an interview on PRI's The Takeaway, a public radio program that invites you to be part of the American conversation.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?