Helen Oyeyemi rewrites Snow White as a tale about race and identity in America

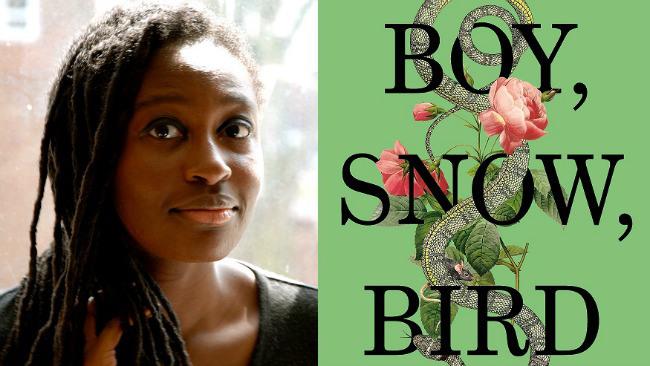

Helen Oyeyemi and her fifth novel, which explores race using the tale of Snow White.

When Helen Oyeyemi was ten years old, reading Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women caused her so much pain that she decided to fix the story herself — directly into the text of the book. She says she has been “fixing” stories ever since.

Born in Nigeria and raised in London, Oyeyemi excels at a particular kind of literary mashup — thoughtfully blending age-old folk tales and supernaturalism with more or less modern stories and characters. Her latest novel Boy, Snow, Bird, borrows from Snow White to tell the story of three young women living in a small American town.

Set in Massachusetts in the 1950s and ’60s, the story centers on a young woman, called Boy Novak, who has a difficult past. She tries to run away from it, but finds herself unexpectedly becoming a wicked stepmother.

“In a lot of ways,” Oyeyemi says, “it's a story about thinking that you’re not involved in something and then suddenly finding that you’re right in the middle of it.”

The Snow White idea of “skin as white as snow” becomes potent as we realize that there are black characters in the book who are “passing” as white. Oyeyemi chose to set the novel in America because she sees “passing as white” as a uniquely American thing.

“There aren’t many accounts of it happening in Europe," she explains. “But also it seems to say something about the very mixed-ness of America.”

Oyeyemi admits her reinterpretation of the Snow White tale stems from a somewhat biased reading of the story.

“Obviously you have reasons for taking a story apart,” she says, “Mine was to take it apart and to expose the mirror as the villain, because I feel that in the original story, the mirror just gets away with it. I had to point out that the mirror is not the arbiter of who’s the fairest of them all.”

Oyeyemi says she wanted to write about “how difficult it is to be yourself when other people won’t let you be, when they take your appearance and just hang any number of assumptions on that.” At one point in the book, Boy confronts the differences in complexion of her adopted child, Snow, and that of her own child, Bird:

"Everybody adored Snow and her daintiness. Snow’s beauty is all the more precious to Olivia and Agnes, because it’s a trick. When whites look at her, they don’t get whatever fleeting, ugly impressions so many of us get when we see a colored girl — we don’t see a colored girl standing there. The joke’s on us."

Though she is a black woman who grew up in London, Oyeyemi says her book does not draw upon personal experience. Her approach to writing, however, is heavily influenced by the enormous number of books she read as a young girl.

When she was a teenager, Oyeyemi suffered from clinical depression. She was suicidal, she says, “in a particularly reckless way.”

“I was just very ready to throw away my life. I don’t think I understood that there was anything to live for … Weirdly, that was a time at which I felt my most powerful. It was strange: my parents would tiptoe around me, teachers would tiptoe around me — because they knew that I could do it at any time. They just left me to find reasons to live, which I found in books — which sounds very cheesy, but all I wanted to do was read.”

By the age of fifteen, Oyeyemi was reading Kafka and Camus, and she fell in love with the books of Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

“The thing is,” Oyeyemi says, “I don’t tend to pay much attention to genre, which is why my writing is the way it is, with so many shifts in tone and register. I’m just as comfortable with Hard Realism as I am with fantasy stories where people fly away with the washing sheets.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?