Many immigrants in the US know this particularly dangerous train ride very well

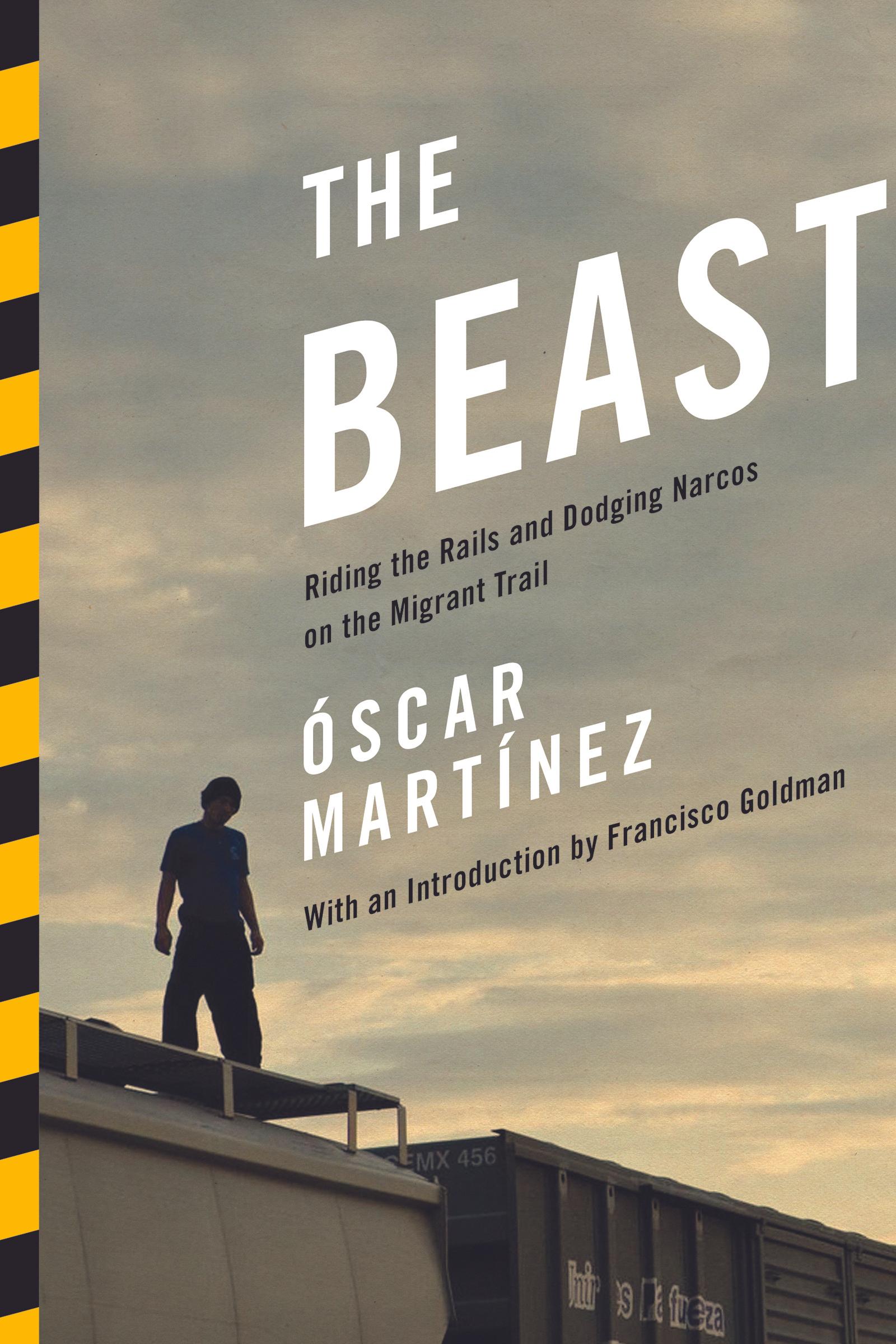

Migrants, mostly from Central America, take trains nicknamed “The Beast” through Mexico to the US border.

There's nothing hopeful about a trip on "The Beast."

That what migrants, mostly from Central America, call the trains that carry them through Mexico to the US border. And it's also the name of Óscar Martínez's latest non-fiction book.

Martínez, a journalist from El Salvador with the digital news publication El Faro, writes about his experiences riding on the roof of La Bestia.

"The Beast is called 'La Bestia' because it is this kind of savage, animalistic journey through a forgotten part of Mexico — a lawless part of Mexico, away from big cities, in these rural areas — places where there is no control," says Daniel Alarcón, executive producer and co-founder of Radio Ambulante, which tells Latin American stories in both English and Spanish.

Earlier this year,US Customs and Border Protection reported a 55 percent increase in the number of Central Americans attempting to cross the US-Mexico border, in part because of increasing drug-related violence back home. And Martínez's book is a brutally honest and dark portrait of the harrowing trip Central Americans take to escape the violence and extreme poverty.

Martínez says when he talks about his book, people are often surprised to hear that such a horrible trek happens so close to the US. "When you see the reactions here, it's like you are talking about Mars — something so far away, and it's not so far," Martínez says. "Half of my country lives here — in Los Angeles. It's shocking. A lot of people cross hell before they've been here [in the US.]"

"You're putting your life in god's hands when you step on that train," Alarcón adds.

Migrants are known to run alongside the train and jump onto it, which results in many injuries and deaths.

"The Beast, in a way, is like a chess game — if you make a bad move, then the consequences can be very rough," Martínez says. "For example, there is a lot of people who lose legs, arms, life on the train."

Alarcón says the book's frankness is actually refreshing, amidst the hopeful immigrant stories out there.

"That's one of the things I really loved about the book," says Alarcón. "There's none of that romanticism of immigrants journeying forward, full of hope, towards a better life. There's just a real harsh realism — a sense that people are taking on this journey because they have to, because they don't have another choice. I really respect that about the book, there's none of this nostalgic gloss of 'Oh, we're going to find something better out there!' They just have to do it."