Russia’s moves in Ukraine are giving China a headache

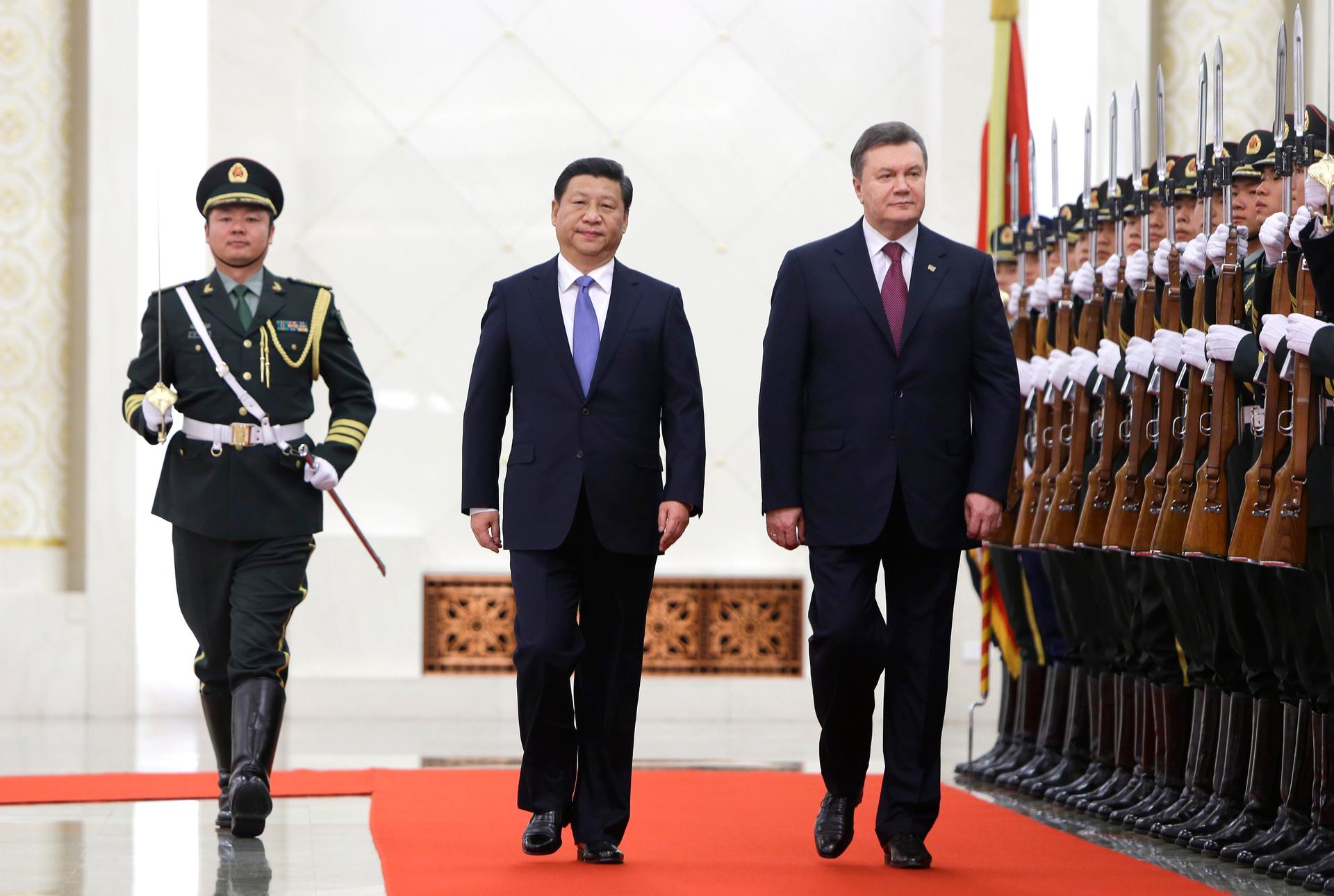

China’s President Xi Jinping hosted his Ukrainian counterpart, Viktor Yanukovich, at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, back in December 2013.

The state of the Sino-Russian relationship is strong. As China's president likes to say, the People's Republic of China has no better friend than Russia. But Beijing has also developed close cooperation with Ukraine in recent years. And the crisis in the former Soviet Republic puts all that, and more, at risk.

China is a big importer of grain, and Ukraine's agricultural system is one of the strongest in Europe. Beyond their trade in grain, Beijing and Kiev have built up military ties. China has purchased large amounts of weaponry from Ukraine, including an aircraft carrier.

All that cooperation was on display as recently as December. Protests raged in the streets of Kiev, but then-president Viktor Yanukovych took time for a state visit to China. He shook hands in front of the cameras with Chinese President Xi Jinping, who reportedly ponied up investments for Ukraine worth $8 billion.

“It just showed that the Chinese government was not anticipating that Yanukovych would be gone so soon,” says Dali Yang, a political scientist at the University of Chicago.

With a new US-backed government in Kiev, the leadership in Beijing now has to wonder if the flow of Ukrainian grain and weaponry is going to dry up. “The developments certainly represent a setback for relations between China and Ukraine,” Yang says.

It's safe to say that the Chinese government was less than sanguine about the mass demonstrations in Ukraine that eventually brought down Yanukovych. This coming summer will be the 25th anniversary of China's bloody crackdown on protestors in Tiananmen Square.

Yang says China's leaders felt the same way about the 'Orange Revolution' in Ukraine a decade ago, all the other so-called 'Color Revolutions', along with the more recent Arab uprisings.

“Every time something like that happens, it just makes the Chinese much more alert to the potential for instability within China,” he says.

Events in Ukraine have touched a nerve for Chinese nationalists. Take, for example, an editorial that ran in the Global Times this week. It laid the blame for the unrest squarely on “pressure from the West,” and said the Chinese public should throw its support behind Moscow.

“Russia has been resisting the eastward trend of western forces in Ukraine, which is important not only to its own fate but also to China's strategic interests,” the editorial said. “Russia and China are strategic buffer zones for each other. If Russia led by Putin is defeated by the west, it will deal a heavy blow to China's geopolitical interests.”

Chinese leaders may or may not agree with this assessment, but they're being far more careful in their public statements. That's because Beijing is uneasy about Russia's latest actions in the Crimea region.

“This is probably the biggest dilemma in Chinese foreign policy since the end of the Cold War,” says Bruce Gilley at Portland State University. Gilley is an expert on Chinese politics.

Russian moves in Crimea, and the downfall of Yanukovych, means that President Xi and his government are forced to juggle conflicting interests.

“Their natural reaction is to side with Russia in this crisis,” Gilley says. “This is consistent with their grand strategy to weaken US and western global leadership.

“On the other hand, they have national interests at stake here, which involve their relationship with Ukraine and wanting to not support any violation of [another] country's territorial boundaries,” he adds.

For the Chinese government, the principle of non-interference is sacrosanct. Think Tibet, Xinjiang and Taiwan. If any of these potential trouble spots ever erupts, Beijing would not welcome outside “meddling.”

It is difficult to spin Russia's aggressive stance in Crimea as something other than outside intervention. And that presents problems for Beijing.

“China doesn't want to tie itself to a global troublemaker,” Gilley says. That would undermine the reputation China's government is trying to cultivate for itself as a force for global peace and stability.

Secondly, Gilley says, “this crisis has the potential to create a slowdown in the global economic recovery, just at the time when the Chinese currency has been taking a hit on currency markets.”

China's leaders must be concerned about unrest in Ukraine becoming a drag on their own economy. And that is something President Xi might have brought up when he spoke with Russian President Vladimir Putin on Tuesday.

In a statement issued Thursday by China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a top official stressed that the rights of all ethnic groups in Ukraine should be accommodated. He also called for all parties to exercise restraint.

The carefully worded message probably fell short of the kind of endorsement that Moscow was hoping to hear from its friends in Beijing.

The state of the Sino-Russian relationship is strong. As China's president likes to say, the People's Republic of China has no better friend than Russia. But Beijing has also developed close cooperation with Ukraine in recent years. And the crisis in the former Soviet Republic puts all that, and more, at risk.

China is a big importer of grain, and Ukraine's agricultural system is one of the strongest in Europe. Beyond their trade in grain, Beijing and Kiev have built up military ties. China has purchased large amounts of weaponry from Ukraine, including an aircraft carrier.

All that cooperation was on display as recently as December. Protests raged in the streets of Kiev, but then-president Viktor Yanukovych took time for a state visit to China. He shook hands in front of the cameras with Chinese President Xi Jinping, who reportedly ponied up investments for Ukraine worth $8 billion.

“It just showed that the Chinese government was not anticipating that Yanukovych would be gone so soon,” says Dali Yang, a political scientist at the University of Chicago.

With a new US-backed government in Kiev, the leadership in Beijing now has to wonder if the flow of Ukrainian grain and weaponry is going to dry up. “The developments certainly represent a setback for relations between China and Ukraine,” Yang says.

It's safe to say that the Chinese government was less than sanguine about the mass demonstrations in Ukraine that eventually brought down Yanukovych. This coming summer will be the 25th anniversary of China's bloody crackdown on protestors in Tiananmen Square.

Yang says China's leaders felt the same way about the 'Orange Revolution' in Ukraine a decade ago, all the other so-called 'Color Revolutions', along with the more recent Arab uprisings.

“Every time something like that happens, it just makes the Chinese much more alert to the potential for instability within China,” he says.

Events in Ukraine have touched a nerve for Chinese nationalists. Take, for example, an editorial that ran in the Global Times this week. It laid the blame for the unrest squarely on “pressure from the West,” and said the Chinese public should throw its support behind Moscow.

“Russia has been resisting the eastward trend of western forces in Ukraine, which is important not only to its own fate but also to China's strategic interests,” the editorial said. “Russia and China are strategic buffer zones for each other. If Russia led by Putin is defeated by the west, it will deal a heavy blow to China's geopolitical interests.”

Chinese leaders may or may not agree with this assessment, but they're being far more careful in their public statements. That's because Beijing is uneasy about Russia's latest actions in the Crimea region.

“This is probably the biggest dilemma in Chinese foreign policy since the end of the Cold War,” says Bruce Gilley at Portland State University. Gilley is an expert on Chinese politics.

Russian moves in Crimea, and the downfall of Yanukovych, means that President Xi and his government are forced to juggle conflicting interests.

“Their natural reaction is to side with Russia in this crisis,” Gilley says. “This is consistent with their grand strategy to weaken US and western global leadership.

“On the other hand, they have national interests at stake here, which involve their relationship with Ukraine and wanting to not support any violation of [another] country's territorial boundaries,” he adds.

For the Chinese government, the principle of non-interference is sacrosanct. Think Tibet, Xinjiang and Taiwan. If any of these potential trouble spots ever erupts, Beijing would not welcome outside “meddling.”

It is difficult to spin Russia's aggressive stance in Crimea as something other than outside intervention. And that presents problems for Beijing.

“China doesn't want to tie itself to a global troublemaker,” Gilley says. That would undermine the reputation China's government is trying to cultivate for itself as a force for global peace and stability.

Secondly, Gilley says, “this crisis has the potential to create a slowdown in the global economic recovery, just at the time when the Chinese currency has been taking a hit on currency markets.”

China's leaders must be concerned about unrest in Ukraine becoming a drag on their own economy. And that is something President Xi might have brought up when he spoke with Russian President Vladimir Putin on Tuesday.

In a statement issued Thursday by China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a top official stressed that the rights of all ethnic groups in Ukraine should be accommodated. He also called for all parties to exercise restraint.

The carefully worded message probably fell short of the kind of endorsement that Moscow was hoping to hear from its friends in Beijing.