A history of the modern world as told by everyday throwaway ephemera

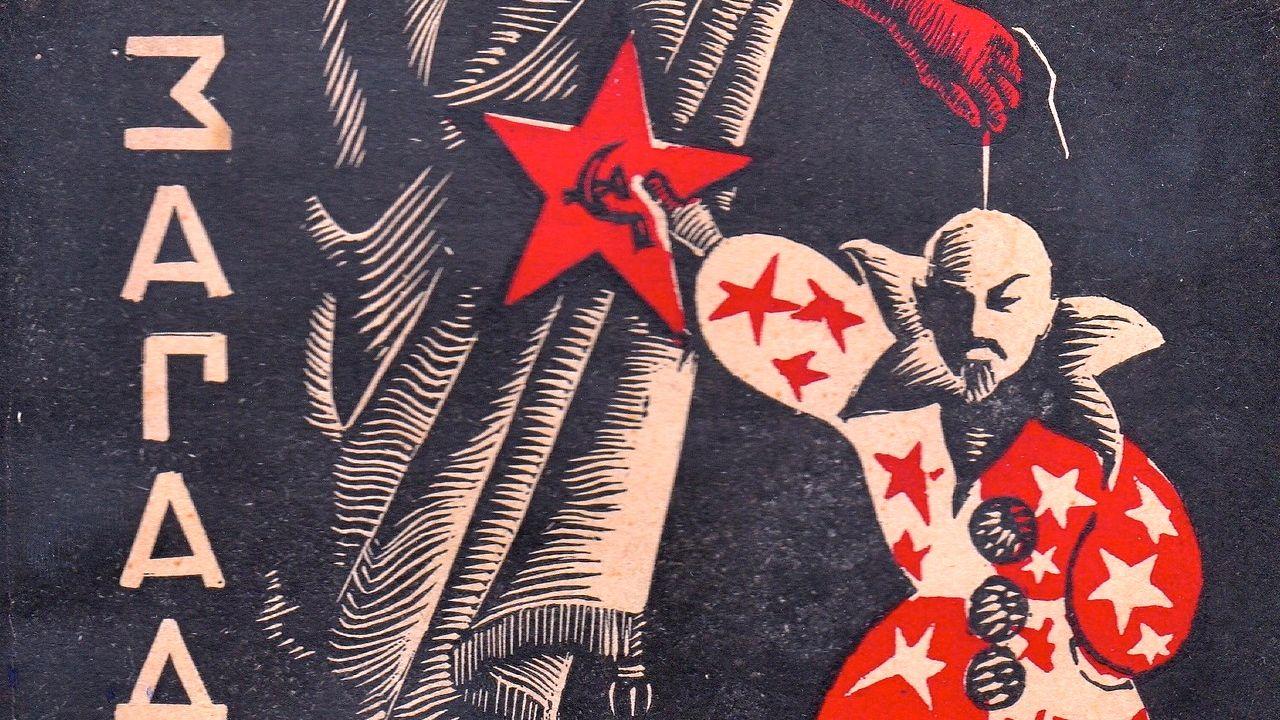

Detail of a Russian book jacket

A couple of months ago a weird flyer appeared all over lower Manhattan. “Connect With Another Human Being Naked Over Tea,” it said. A guy named Koji was looking for a more interesting way to cover rent and this is what he came up with. So I pried the flyer from a pole and took it home.

I’ve spent half my life saving things most people associate with the recycling bin — zines, playbills, ticket stubs — and it turns out I’m not alone. The collection of “ephemera” is on the rise, as are a new wave of rare book dealers punking up the definition of what it means to be a literary collectible.

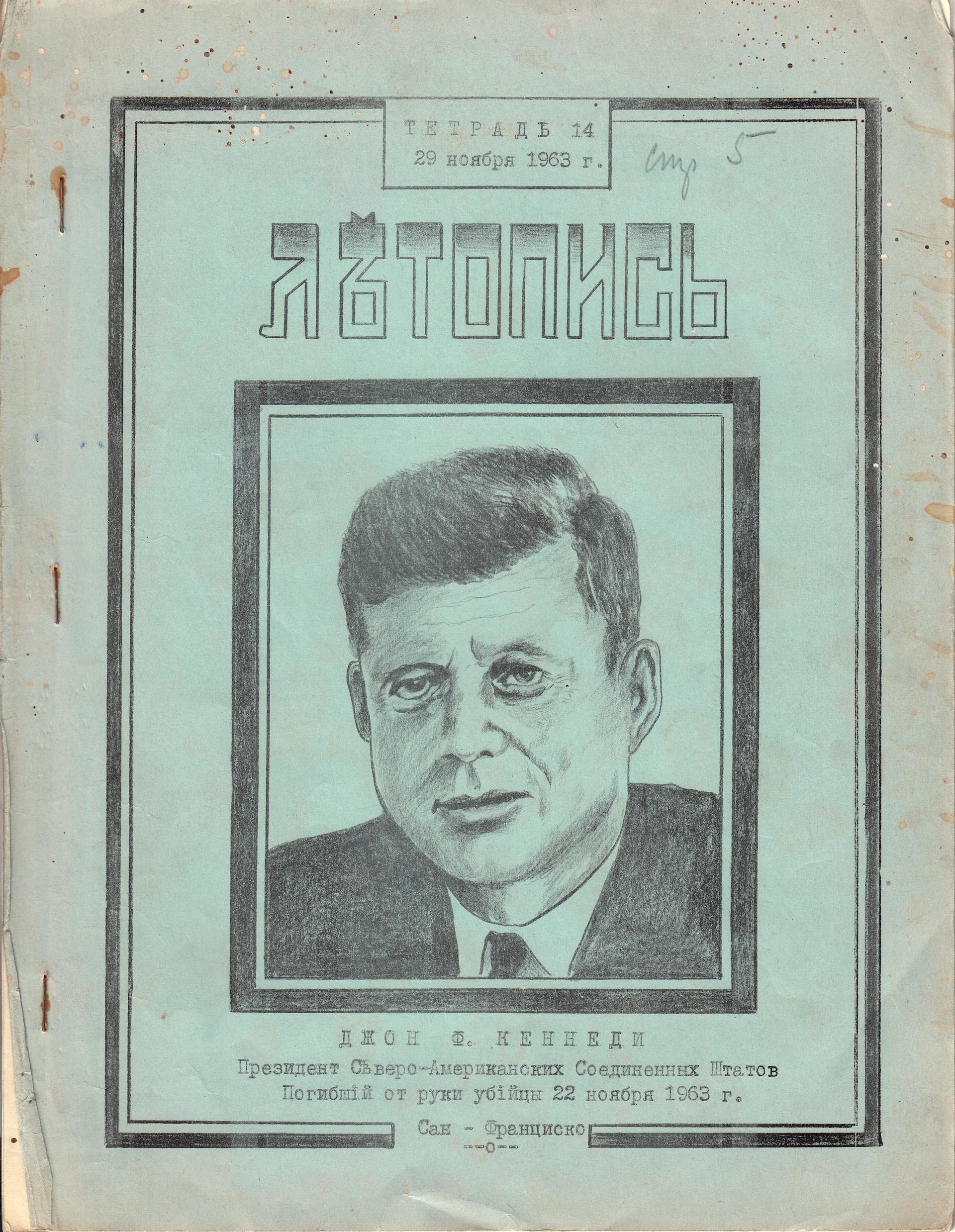

Philipp Penka is a Berlin-based dealer with a special focus on Eastern European samizdat — illegal, self-published material that circulated during the Soviet era.

Philipp Penka is a Berlin-based dealer with a special focus on Eastern European samizdat — illegal, self-published material that circulated during the Soviet era.

“Often you would only have a night to read it,” Philipp says. “You’d have to squint really hard to make out the text, and then you’d pass it on. So they weren’t made to be…kept or to put on your shelf or to look pretty, right?

Ten pieces of rice paper stuffed into a typewriter — you’d be lucky if you got a copy made from the top sheet. That’s how my Dad, who grew up in the Soviet Union, described the samizdat he read. He laughed when I asked him whether he took any with him when he left for the US. This was the analog equivalent of Snapchat. You read it; it vanished.

“I had a wonderful copy of Mikhail Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita,” Philipp told me, “that as it turned out was actually published on one of the first computers that they had in the Soviet Union. So this was printed from a mainframe computer and then later bound for circulation.”

I wish I could play some kind of audio for you here, to illustrate how samizdat was made and shared. Instead you’re hearing the musical equivalent — a song by Russian dissident Alexander Galich recorded in the 60s, that circulated illegally on cassette tape. But today in the age of the over-share, the distributors of this mysterious medium — whether musical or print — remain anonymous. That’s part of what makes collecting it so exciting, as Philipp explains.

“There’s a sense now for many people that everything has already been collected, everything’s been digitized, it can be found on Google Books, and people are realizing this just isn’t true. That’s, I think, where some of the thrill comes from in collecting ephemera, that you are able to find these things and in many cases sort of document historical phenomena that aren’t recorded, that aren’t in libraries.”

I was surprised when Phillip Penka told me that most of the samizdat he sells goes right back to the former Soviet bloc, to native collectors eager to reconstruct the Communist era’s hidden history. Not all ephemera was published by dissident freedom fighters though — mass-produced government propaganda is just as sought after.

Alex Akin became the house expert on Asian ephemera at Bolerium Books in San Francisco, when he discovered one of the earliest gay travel guides to Taiwan buried in their storage room. He told me a story about a family yard sale where he tried selling some extra copies of Mao’s ‘Little Red Book’ and was confronted by an elderly Chinese man.

“He pointed to his mouth and said, ‘You know why my teeth are like this?’ Because red guards who were waving these books around kicked me in the face until my teeth were gone. And it really drives home the fact that these are things that had consequences in their time, these are not just playthings.”

I have to admit, I’m one of those people who finds Communist propaganda mysterious appealing — even beautiful. And a lot of kids decorating their dorm-rooms apparently agree. I have a closet full of Stalin-centric Soviet magazines flea-marketed during my last trip to Russia. As the daughter of political refugees, I’m not sure what accounts for my attraction to dictator kitsch, but according to Alex, it doesn’t make me a Stalinist:

“I think one mistake a lot of people make is they assume that someone’s collection reflects their own values,” say Alex, “but in fact you often see, for example, the most serious collectors of anti-Semitic propaganda in the US, almost all of them are Jewish. The biggest collectors of anti-Chinese material, say from the 1880s, some of them are Chinese-American lawyers.”

The most ephemeral ephemera, however, wasn’t published by groups, but handmade by a single individual. To Adam Davis, whose shop, Division Leap in Portland, Oregon deals in post WWII ephemera, it’s all about democracy.

“When you look at a photocopied punk zine, or a flyer for a show somebody made themselves in the middle of the night at Kinkos, it has this aura of a participatory culture. The message seems to be, ‘You could do this yourself.’ Like, you should go out and do this, you should start a zine, you should make a flyer. It’s amazing because in a way it’s also local too. Like a flyer on a pole in a major city is a way of exposing your work to somebody who wouldn’t see it otherwise because they’d never think to type your name into a search engine.”

Ok, but given this stuff is so easy to make, how does the collector who paid Adam $2500 for the original flyer advertising the first New York performance of John Cage’s ‘Silence’ know he’s getting the real deal, not a copy made at Kinkos yesterday? It’s not easy — authenticating ephemera requires getting scientific about stuff like vintage staples and the thickness of Xerox machine ink.

Ok, but given this stuff is so easy to make, how does the collector who paid Adam $2500 for the original flyer advertising the first New York performance of John Cage’s ‘Silence’ know he’s getting the real deal, not a copy made at Kinkos yesterday? It’s not easy — authenticating ephemera requires getting scientific about stuff like vintage staples and the thickness of Xerox machine ink.

But the ephemera of today is more likely to involve jpegs and text grabbed from tumblrs:

“Ok, so we’ve heard ‘lasercut,’ we’ve heard ‘pop-up,’ some stuff about sowing…Should we try to sow the binding…?”

That’s Garnet Hertz, leading a zinemaking workshop at NYC Resistor, a hacker collective based in Brooklyn. Hertz has led workshops like this all over the world, often at hacker spaces, from Chile to Canada, with China up next. I just assumed people who spend a lot time with micro-controllers and blinky tape wouldn’t geek out over something so… primitive? I was wrong.

The collective uses a mash-up of high and low technology to document their story. A laser cutter, computers, an etching press, scissors, glue, and Kinkos, all play a role in bringing Resistor’s zine to life.As a snapshot of Resistor’s history, it’s probably ephemeral, but as an artifact, it might just be an illuminated manuscript of the 21st century. In any case — I won’t be throwing it away.

See a slideshow of ephemera from The World's newsroom.