History of Iraq part I: the British legacy

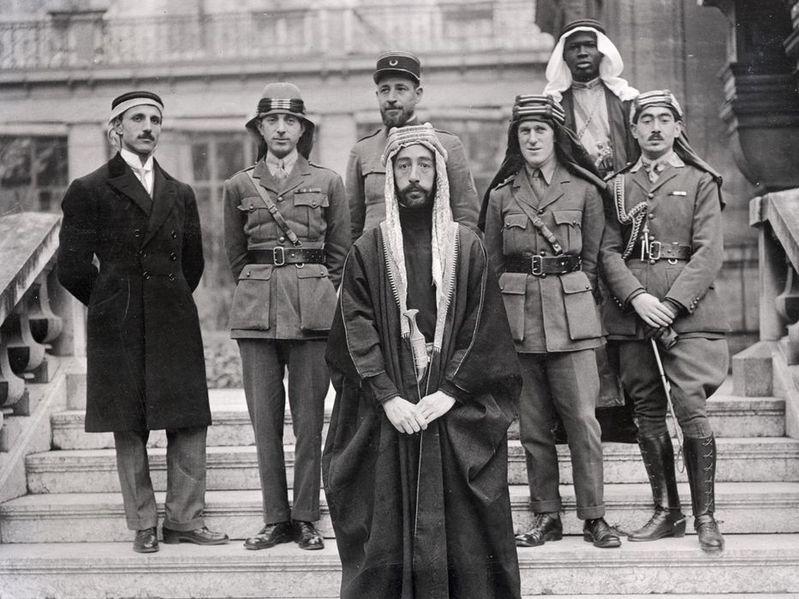

Left to right: Rustum Haidar, Nuri as-Said, Prince Faisal (front), Captain Pisani (rear), T. E. Lawrence, Faisal’s slave (name unknown), Captain Hassan Khadri.

The land now known as Iraq has an ancient history as Mesopotamia – the fertile valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers and the site of the Biblical Garden of Eden.

But as a country, Iraq did not exist before the 20th century.

At the beginning of World War One it was a collection of three provinces that were part of the sprawling Ottoman Empire run by the Turks. By then the empire was falling apart and other powers were coveting its territory. During the war, the British and the French held secret negotiations.

Historian Margaret MacMillan says they came to an understanding over the Ottoman lands of the Middle East.

"The agreement is roughly that the British would get what became Iraq and what became Palestine and then later on Palestine and Transjordan, and that the French would get what became Lebanon and Syria," she says.

Much of the subsequent horse-trading had to do with oil. Under the original agreement, the French were supposed to get the province of Mosul in the north of Iraq. But the British began to suspect there was oil there and backpedalled on that part of the deal. Reluctantly the French let Mosul go. But only on condition they would get a share of any future oil revenues.

"You had sort of pools, sort of muddy pools lying around which used to spontaneously burst into flames, so you could tell there was oil there," MacMillan says. "And although oil was not yet as enormously important as it was going to become—I mean coal was still the main fuel that countries used – but it was becoming important. The British Navy had converted to oil burning ships just before the First World War and so sources of oil were enormously important."

So important, that after the war a French official called oil "the blood of victory." Oil was not the only complication after the war. For years the British had been encouraging the rise of Arab nationalism in order to weaken the Ottoman Empire. Margaret MacMillan, who has written a new history of the Paris peace conference that followed the war, says the British now had to deal with the consequences.

"The British encouraged the Arabs to revolt with a rather vague set of promises that the Arabs believe literally and the British did not, that the Arabs would have their own independent kingdoms after the war was over. And so you have the Arabs thinking they've been promised independence, the British and the French busily carving up the Arab Middle East, and so you get by the time the peace conference opens a really complicated situation," she says.

The Arabs hoped their dream of ruling themselves would come true in Paris in 1919. They were represented there by the charismatic Prince Faisal. He was the son of Hussein, the Sharif of Mecca, guardian of the holy places. The Arabs also had the support of Faisal’s friend, the British colonel T.E. Lawrence – Lawrence of Arabia. But in the end, the Arab cause was shunted aside by the three big powers, Britain, France and the United States.

"Their main concerns were to deal with the German peace and also to set up the League of Nations to try and establish a new world order," MacMillan says. "I think you really got an attitude among the big powers in Paris, which even the Americans shared, that the Arabs were basically a people at a lower stage of development, that they wouldn't be ready to rule themselves, that they would basically accept what they were told by the powers and behave in a nice quiet way."

How wrong that turned out to be. In April 1920, the brand new League of Nations awarded the Iraq mandate to Britain. The borders of Iraq were set. But by June the population was in full revolt. The British crushed the rebellion, but it took months, and thousands of lives. They had no idea how they were going to rule their new territory.

John Bagot Glubb was a British officer in Iraq during this period. He told his story to the BBC.

"While I was there, 1921, Winston Churchill went out to Cairo and held a conference to settle what we were going to do with all this Middle East business which we'd got on our hands as a result of having driven the Turks out. The whole place was out of control. It was all armed tribes whom even the Turks had never subjugated in their time," he said.

The decision in Cairo was to install a British-friendly Arab leader as King of Iraq. The conference marked the end of a significant policy debate among British officials. The man running Iraq for Britain at the time was Arnold Wilson. He favored British rule for the new country. His deputy, Gertrude Bell, favored Arab rule. Bell was extraordinary for her time. She had travelled all over the Middle East. She had slept out in the desert. She had worked for British intelligence during the war. And she was friendly with Prince Faisal and other Arab leaders.

MacMillan says in the end, Bell won out over her boss Arnold Wilson.

"At the end of the war she was in Baghdad and she began to realize that simply handing over the Arab parts of the Middle East to rule by Britain and France was probably going to be a mistake," she says. "She began to realize that Arab nationalism was becoming a force to be reckoned with. So she and Arnold Wilson really fell out. With Arnold Wilson looking for some old form of either direct or indirect rule by Britain and Gertrude Bell arguing we actually have to move on, we have to find some sort of Arab ruler."

The obvious choice was Bell’s friend Prince Faisal, who had represented the Arabs in Paris. He had already had a brief stint as the ruler of Syria in 1920. But the French kicked him out shortly after they took over the mandate there. The British now thought he could serve their purposes in Iraq.

"And so very hastily Faisal was made King of Iraq and Gertrude Bell designed a very nice coronation for him," MacMillan says.

The king's first task was to create a sense of nationhood where there had been none—out of a population of different peoples, languages and religions, with very little in common except the territory they now shared.

Charles Tripp, the author of “A History of Iraq,” says King Faisal faced a huge challenge.

"He was confronted with a country in which large numbers of the population didn't know they were Iraqi, and didn't actually particularly want to be Iraqi, if that meant the central government or the British breathing down their necks, says Tripp. "And so he had to win the trust of large numbers of Iraqis to make the experiment work. And I think he was very well aware of the fact that people would regard him as a British puppet, and yet at the same time he was well aware of the fact that if he defied the British he would lose the throne. So he had to play this balancing act."

But even Faisal chafed under British rule. An Anglo-Iraqi treaty signed in 1922 could not mask the fact that his country was effectively under military occupation. An oil deal signed in 1925 only underlined its subjugation. The agreement granted Iraq token royalties from any future oil revenues, but denied it a share in the British-dominated Turkish Petroleum Company. Said Aburish is a writer on Arab affairs and a former consultant to the Iraqi government.

“The agreement between the British and Iraq regarding the rights to the oil of the country is one of the most criminal documents I have ever read in my life,” Aburish says. “It is aimed at keeping Iraq in the dark ages.”

That agreement suddenly began to matter when oil finally gushed from a discovery well in northern Iraq in 1927. But for all Britain's power it was unable to prevent King Faisal from shepherding Iraq toward greater autonomy. The British agreed to end their rule earlier than planned and grant Iraq independence in 1932. In exchange Iraq negotiated a new treaty with Britain. Iraq would be responsible for its own defense, but Britain would retain air bases and the right to move troops through Iraq in the event of war. Britain would also train the Iraqi military and supply it with equipment.

It was independence after a fashion, but it didn’t solve Iraq’s problems. Internal tensions were chronic. In his writings, King Faisal lamented his failure to forge a common Iraqi identity for his subjects. He never achieved that goal. He died while seeking medical treatment in Switzerland in 1933. Muriel Lucie-Smith was a governess at the palace in Baghdad at the time. She shared her recollections with the BBC.

"He went away on a Friday. He had been ill. The following Friday, early in the morning, half past six, I was getting dressed and a eunuch came in and said the prime minister wants you. I thought I couldn't understand him. But he wouldn't go away and he beckoned me to come. So I went down. There was the prime minister. He told me the King was dead," she said.

The throne went to Faisal's son Ghazi. The new king was more anti-British than his father but also less politically astute. In the end, his reign was short; he was killed in a car crash in 1939. His son, Faisal the Second, was only three years old, so a regent was appointed to rule in his stead.

It was a tense time. World War II had started and the British wanted assurances Iraq would remain loyal. The regent was reasonably pro-British but he was threatened by a group of powerful army officers who were not. In 1941, the officers rallied round their leader Rashid Ali. They formed their own government, chased the regent out of the country, and announced their allegiance to Germany. Britain wouldn’t stand for it and sent forces to stamp out the rebellion.

BBC Reporter Richard Dimbleby accompanied the soldiers.

"While the British troops inside the Royal Air Force Baghdad station at Habbaniyya are pushing back the rebel Iraqis who surrounded them, farther west in the Iraqi desert another British force is moving forward, clearing up the frontier zone and removing Iraqi resistance from certain points on the Kirkuk pipeline," Dimbleby reported at the time.

The British secured the pipeline and reoccupied Iraq. Soon it was business as usual again. British-friendly politicians returned to power. The Regent kept the throne warm for Faisal the Second. And British attitudes were as colonial as ever, as in this excerpt of a newsreel from the time:

"From the towering mosque in Baghdad comes the Regent of Iraq after Friday prayers. He is Regent for the 7-year-old King Faisal the Second, the grandson of Faisal, the first king. They take great care of this little monarch when he visits the camp of Britain’s Empire Army and he's a lucky young man because he's getting a first hand view of all sorts of thrilling things like real guns and a field wireless set. Even a boy king gets an ordinary boy's thrill out of that."

Beneath the cinematic gloss, Iraq was still roiling with discontent. Oil profits had been flowing out of the country for years. Inside the country, landowners held peasants in virtual serfdom on huge estates, according to Tripp.

"For many people, the social misery that that produced, and the inequalities, was a very radical spur to recreating Iraqi society. It’s what gave the Iraqi Communist Party enormous social basis," he says.

Arab nationalism and anti-Western sentiment were also on the rise. But the Iraqi monarchy clung to the past. In 1956, Iraq joined the Baghdad Pact, joining it with Britain, Turkey, Pakistan and Iran. It was an anti-communist alliance backed by the United States, a new player in the region. The same year, King Faisal the Second, now old enough for the throne, reaffirmed his friendship with Britain.

"The long and happy years of association between our two countries has recently been even more strengthened through the Baghdad Pact," the King said in a speech. "I know we shall go into the future in peace and amity, each helping the other, as true friends."

But two years later, King Faisal met his end. A group of army officers bent on ending the monarchy and establishing a republic had launched a successful coup. Faisal's relative, King Hussein of Jordan, broke the news to the world.

"The murderers and rebels have assassinated my brother and childhood friend, his majesty King Faisal, together with his Royal Highness the Crown Prince and all members of the royal family," he announced.

This time the break with the British was permanent. But the British legacy in Iraq endured. Remnants of colonial rule persist even now, according to Tripp.

"Strong central power exercised from Baghdad, an intolerance of provincial autonomy, a contempt in many ways for popular forms of rule, and the huge and continuing importance of the armed forces in Iraq’s politics," says Tripp.

It was a legacy set in motion during and after the First World War. Historian Margaret Macmillan says the Western statesmen making decisions about the Middle East then were typical for their era. They had little regard for the inhabitants of the places they were carving up on the map.

"They made what were often casual, and in many ways offhand decisions, and as often happens, your casual and offhand decisions are sometimes the ones that come back to haunt you. And so the British created Iraq. I don't think they ever thought that it would turn into the problem it later turned into," MacMillan says.

The revolution of 1958 ended the monarchy but it did not bring stability. Ten years of coups and countercoups followed—paving the way for the rise of the Arab Socialist Baath Party —and the rule of Saddam Hussein.