The US and Iran part III – the hostage crisis

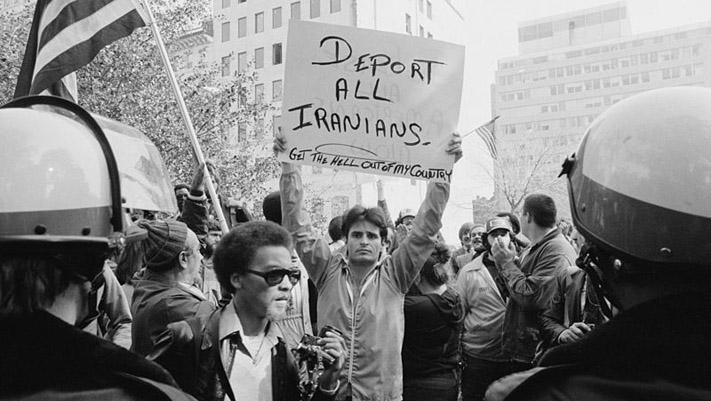

A man holding a sign during a protest of the crisis in Washington, D.C., in 1979.

The upheaval following the overthrow of the Shah of Iran was profound.

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned from exile in February 1979. The old regime collapsed a couple of weeks later, but it was not clear what sort of government would replace it.

Shaul Bakhash, who teaches Middle East history at George Mason University, was still in his native Iran during the revolution. He says the joy on the streets there quickly gave way to fear.

"Within days of the collapse of the old regime, the executions of members of the former regime began and each morning we woke up to grisly pictures in the newspapers of cadavers of former ministers, army generals, intelligence officers, who had been executed the night before," he says.

The United States watched with trepidation. The Shah had been considered a crucial ally. Khomeini, with his fierce anti-American rhetoric, was just the opposite.

But US officials were relieved when Khomeini picked a relative moderate, Medhi Bazargan, to be the new prime minister.

"In hindsight you could say we were very naive, or we were very stupid, but the idea was to give the relationship a chance," says John Limbert, who was a political officer at the US Embassy in Tehran at the time.

At first the signals were good. Bazargan wanted to normalize relations with the United States. The two sides started to communicate. They even shared some intelligence.

Meanwhile the exiled Shah of Iran was looking for a home. Powerful friends argued he should be allowed into the United States. But Carter Administration officials feared a backlash in Iran. The initial decision was to keep him out. But in the fall of 1979 it became clear that the Shah was dying of cancer. He wanted to come to New York for treatment.

President Carter decided to let him in.

Bruce Laingen, the charge d'affaires at the American Embassy in Tehran, received an urgent message from Washington.

"I was instructed to seek out the prime minister immediately, tell him the Shah was being admitted to the United States for medical treatment. That it was a purely humanitarian gesture, that it did not suggest in any way that we regarded him as a political figure of leadership in Tehran," Laingen says.

But that's not how it looked to Iranians who supported the revolution. Their greatest fear was that the United States and the Shah would get together to overthrow the new regime.

Political scientist Mark Gasiorowski says Iranians of a certain age all knew the CIA had conspired with the Shah 25 years earlier to overthrow Mohammed Mossadegh, an elected and immensely popular prime minister.

"They came of age believing that the United States had done this fundamentally evil thing and had changed the course of Iranian history-and they're basically right about that-but they blew this up into a great, you know myth, and this myth was largely responsible for the anti-Americanism of the Iranian revolution," Gasiorowski says.

US officials knew Khomeini and his followers hated the United States, but they were clueless about the depth of that hatred.

Bakhash remembers an American diplomat he knew calling him in Tehran during this period.

"He had just come in from the United States and said can you come over and see me at the embassy. I said I can't come near the embassy. And he says well well I'll come over and see you. I said don't come near my house. Don't telephone. But I was astonished that he didn't sense how much hostility there was in Iran towards the US and how risky it would be for any Iranian to show up at the embassy or to have an embassy car drive up to an Iranian's house," he says.

On November 1, Carter's national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski met Prime Minister Bazargan at an event in Algiers. Militant students back in Tehran feared their government was again cozying up to the United States, and that Washington was plotting to reinstall the Shah.

On November 4th 1979, a mob of students overran the US embassy in Tehran. They took 66 American diplomats and marines hostage.

"I was in Iran when the embassy was seized. Had I not been there I would never have imagined how electric the seizure of the embassy was for society as a whole. I mean within hours of the seizure of the street and the whole area outside the embassy was full of tens of thousands of people and those crowds remained around the embassy for days, maybe even weeks, afterwards. It really was a galvanizing moment in the history of the revolution, and helped consolidate the revolution and push it in a more radical direction," Bakhash says.

The hostages assumed the crisis would blow over within 24 hours. A similar attack nine months earlier had been resolved rapidly. But this time Khomeini backed the students. One day turned into two, and then days into weeks and weeks into months.

John Limbert, the political officer, was one of the hostages. He says he quickly learned what all prisoners learn.

"Your thoughts get very focused and you essentially have one, one goal, which is get me out of here. Other things really don't matter very much," he says.

The students demanded the United States turn the Shah over for trial. Then they threatened to put the hostages on trial. They went through the embassy's documents, even reconstituting some the embassy staff had managed to shred. They used notes of meetings between embassy officials and moderates in the new government to taint those moderates.

Limbert says one aim of the hostage takers was to sabotage relations between Tehran and Washington.

"I mean the idea of friendship or a correct relationship in some ways was more threatening to them than outright hostility," he says.

The students certainly helped sabotage the Bazargan government. The prime minister resigned two days after the embassy takeover. In the 25 years since, some of the hostage takers have written memoirs, granted interviews, given their side of the story. They've made it clear they wanted to avert another 1953-style coup. That's the year the CIA organized the overthrow of Mossadegh's government.

Hadi Semati, a professor of political science at Tehran University, was studying in the United States at the time of the hostage crisis, but says he identified with the revolutionaries back home.

"To a lot of us it was understandable in the sense that the students were perceiving another 1953 coup in the making," he says.

Now Semati is amazed when he looks back. He says he and other young Iranians had no idea what it meant to take on a superpower. And they were terribly naive about how the world would see them.

"When I look back myself I think gosh, we didn't understand either what the world was thinking. So it was really a double misperception if you will; we wanted the world to understand us, but at the same time we weren't understanding the world either, how they would perceive all of these things," he says.

The Carter Administration scrambled to come up with a response. First Carter banned oil imports from Iran. Then he froze Iran's assets.

"I must emphasize the gravity of the situation," he warned. "It's vital to the United States and to every other nation, that the lives of diplomatic personnel and other citizens abroad must be protected. And that we refuse to permit the use of terrorism and the seizure of hostages to impose political demands. No one should underestimate the resolve of the American goverment and the American people in this matter."

Carter appealed to the UN Security Council and the International Court of Justice. Both condemned the action and demanded the release of the hostages. But the appeals had no effect. The Carter Administration debated its options.

Former White House official Gary Sick recalls those deliberations in his memoir, "All Fall Down: America's Tragic Encounter with Iran."

"Carter made a really enormous personal and governmental investment in trying to find ways out of this crisis short of military action," he says.

But the Iranians weren't in a mood to negotiate.

Carter's national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski longed to take military action.

"I suppose it's no secret that I was much less optimistic about the negotiations and much more inclined to move toward some use of force. In regards to a conduct which is utterly inacceptable by any international standard," Brzezinski says.

The American public began to mobilize. They rang church bells, they hung yellow ribbons around trees. They demonstrated.

Meanwhile the hostages struggled. Laingen was the most senior American official taken captive. He'd been at a meeting at the Iranian foreign ministry the day the embassy was seized. He and two colleagues were detained there, separate from the rest of the embassy staff. Laingen kept a diary on scraps of hidden paper, jotting down a wide range of emotion.

"Hatred to anger to frustration to hope, a lot of hope, disappointment. I was in charge! I was in charge of that mission. My colleagues, my staff on the other side of town, were being held against their will. That was my pain through the whole time. The captain of the ship syndrome. I couldn't do anything to help my crew," Laingen says.

In April 1980, five months after the embassy was seized, President Carter broke off diplomatic relations with Iran. Later the same month, the United States attempted a rescue mission. It failed almost before it began. Three US military helicopters experienced mechanical difficulties in the Iranian desert. A fourth collided with a transport plane. Eight American crewmen were killed.

Brzezinski says it was a critical moment in the saga.

"Even though we always considered the possibility of a failure, nonetheless the failure itself was a very difficult and painful moment. And gave you a sense that the situation really is becoming increasingly stalemated and mutually destructive. Destructive for American interests and destructive for Iranian interests," he says.

Three months later, in July 1980, the Shah succumbed to his cancer. He died in Egypt, where he'd taken refuge after being pressured to leave the United States following his cancer treatment. Former President Nixon lamented the way the Shah had been treated.

"The Shah has been one of the most loyal friends and allies of the United States," Nixon said. "I think his passing under these circumstances was a great tragedy. I think the handling of this situation by our own administration will be recorded as one of the black pages in the history of American foreign policy."

As time went by, the crisis began to cripple the Carter presidency.

Republican presidential candidate Ronald Reagan exploited the growing perception that Carter was ineffective and weak.

"Let it be our purpose to become so respected throughout the world, that never again will a foreign dictator dare invade an American embassy and take our people," Reagan said.

And, in one of the rituals that grew out of the hostage episode, American news organizations found ways to remind people daily just how long their fellow citizens had been detained.

"And that's the way it is, Monday, November 3, 1980, the 366th day of captivity for the American hostages in Iran. This is Walter Cronkite, CBS News. Good night."

Finally, as 1980 drew to a close, the Iranians were willing to enter serious negotiations to free the hostages.

Deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher and an Iranian counterpart negotiated a settlement in Algiers. President Carter announced the news at the very end of his term in January 1981. In a final humiliation to Carter, the Iranians waited until Ronald Reagan was inaugurated before allowing the planes carrying the hostages to lift off from Tehran. The Americans had been in captivity 444 days.

"It's a beautiful feeling to feel again what freedom is," Laingen says. "I often said when I was held hostage I look forward to the day when I can walk down the road in the rain and have that sense of freedom. You can't sense unless you go to prison yourself that physical freedom itself is terribly important and then all of the other freedoms that flow from that."

The Iranian students and their government succeeded in wounding the United States. They got their revenge for the 1953 coup. But they also hurt themselves and their country in the process, according to Gary Sick.

"They became a pariah state. They became a complete outlaw state. People still remember Iran as this mob of fanatics marching in the street, waving their fists, shouting Death to America, and that's as much as they remember about Iran. That's all they need to know. And for Iran to overcome that image is taking a very very long time. And it's undoubtedly the reason why the United States and Iran don't have relations," he says.

After the hostage crisis, America wanted nothing more to do with Iran.

But as Ronald Reagan soon discovered, Iran would stay near the top of the US foreign policy agenda for a long time to come.