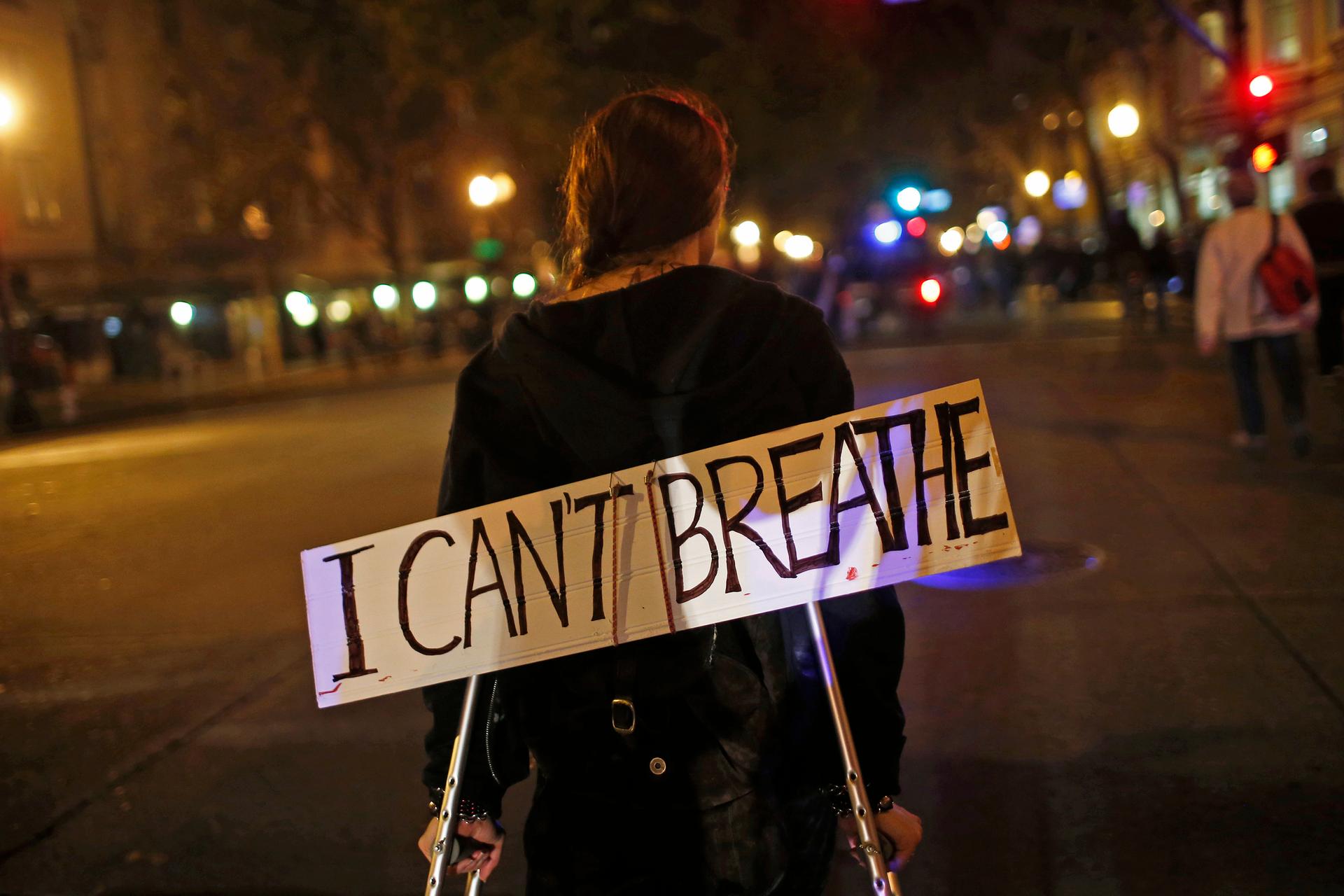

A protester in Oakland, California, on December 3, 2014, wears a sign during a demonstration against the decision by a New York City grand jury not to indict a police officer in the death of Eric Garner.

The police officers who killed Michael Brown and Eric Garner both had their cases brought before a grand jury. In each case, a group of our fellow citizens made the decision not to indict. But most of us aren't especially familiar with how a grand jury works.

The concept comes from our colonial parent, England. "It goes back centuries here," explains London-based legal writer Joshua Rozenberg. "In medieval times, it was drawn from the local neighborhood. And these were men who were expected to look around and report criminal behavior within the community. They're people who actually knew the offenders, as we'd call them today, and could perhaps bring them to justice."

By the 16th century, that morphed into the system we'd now recognize as a grand jury: A group of people listening to a prosecutor's evidence and deciding whether to indict.

But the United Kingdom actually abolished its grand jury system in 1933. "We now send cases that are serious enough straight to jury trial," Rozenberg says. That way, both sides are able to present evidence and make their arguments, which is definitely not the case with a grand jury.

In fact, the UK exported grand juries to most of their former colonies — Canada, Australia, New Zealand — and virtually all of them have stopped using them.

"They are said to be 'putty in the hands of the prosecutor.' In other words, the prosecutor really tells them what he or she wants and they will go along with it," he says. "Or that's what we are told, because we don't really know. We can't watch grand juries at work."

That's why former New York judge Sol Wachtler once famously said that a district attorney could get a grand jury to "indict a ham sandwich." But, Rozenberg points out, "it must be even easier to get the sandwich acquitted if that is what the district attorney may actually want."

The quote, while flippant, actually says a lot about what happened in Ferguson. Robert McCulloch, the St. Louis County attorney, cited the problem of "conflicting evidence" as a reason why Darren Wilson wasn't indicted for Michael Brown's death. But the prosecutor is the one who offers evidence to the grand jury. If the evidence he gives is inconsistent, Rozenberg says that leaves the grand jury in a pickle of sorts.

"You might get some witnesses who say they saw Darren Wilson, the police officer, shoot Michael Brown and he wasn't resisting arrest. Then, of course, you heard Darren Wilson himself and you hear what he says," Rozenberg says. "So this was really what we would regard as a trial, but a trial behind closed doors."

And that's what happened with the Ferguson grand jury. So if this is the case, why do we still have a grand jury system? What's the purpose of a secret procedure in a country that that televises court proceedings?

Rozenberg isn't actually sure. "Why not have everything out in the open and let both sides say, openly, in a public forum, to an ordinary jury what their arguments are — and then let an ordinary jury decide?" he asks.

A lot of people here are asking the same question.