As fracking booms, waste spills rise — and so do arsenic levels in groundwater

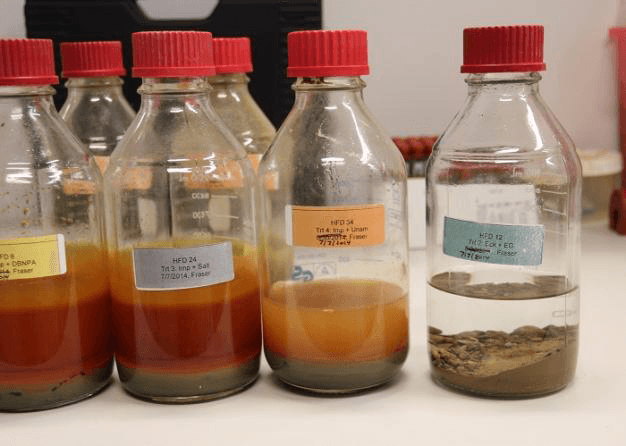

Sediment from a stream bed containing fracking wastewater (jars on the left) developed orange residues after 90 days; sediment from a clean stream bed (jar on the right) did not.

Janice Dumont loves her drinking water.

“Our well water is so good,” says the resident of Cecil Township, a Pennsylvania town just south of Pittsburgh. “I mean, it’s delicious, it’s cold, and there are no water bills.”

But she's worried it may not stay that way for long. Dumont lives near a potentially leaky "impoundment," a site where energy companies store the waste from hydraulic fracturing.

The process, commonly called "fracking," uses high-powered jets of water and chemicals to cut through soil. There are now 8,000 fracking wells in Pennsylvania, producing billions of gallons of "frackwater" — and an average of more than one wastewater spill per week so far this year.

And as the industry booms, scientists from the US Geological Survey, are trying determine the effects of this wastewater on local groundwater and the surrounding environment. "One of the main things we’re trying to do is identify what the important potential pathways to the environment are," says Isabelle Cozzarelli, a geochemist leading the team of USGS researchers.

Her team is looking closely at one question in particular: What happens when tiny organisms in the soil come in contact with frackwater? These bugs are like the Earth’s gut bacteria, Cozzarelli explains.

Some bacteria eat crude oil and the chemicals found in oil and gas waste. So if some crude spills on the ground, it’s like an all-you-can-eat buffet for bacteria. That seems like good news — the bugs can eat the contamination.

But there's a catch: These bugs also need to breathe.

They need to breathe even more when they’re given a large, new food source, like a frackwater spill. There's very little oxygen, but Cozzarelli’s group says the bacteria they study have evolved to thrive in this inhospitable environment.

“If you’re a human and you have no oxygen, you die,” she says. “But if you’re a cool microorganism, you can breathe the nitrate or the iron or the sulfate, because you’ve adapted to be able to do that.”

This is where researchers have found an unexpected problem: the more food the bacteria get from a spill, the more iron they breathe. Iron minerals found in soil are a frequent host for another element: arsenic, a known human carcinogen. When a bacteria breathes in that iron, the arsenic is released and becomes water-soluble. And suddenly unsafe levels of arsenic get released into the groundwater.

This seems to have happened at an oil spill site in Minnesota. Arsenic levels in the groundwater at the site are 20 times above the EPA limit for drinking water.

With so many wells in Pennsylvania, such problems could be huge. “I kind of feel like we’re just trying to catch up,” Cozzarelli says. “The industry’s just gone so quick."

But Pennsylvania's Department of Environmental Protection says it's on top of the wastewater issue. “Management of wastewater from oil and gas development is, in my opinion, the most critical environmental issue associated with the activity,” says the DEP's Scott Perry.

The department closed one impoundment this year after the company that owns it, Range Resources, discovered high salt levels in the soil beneath its liner. In September, the company agreed to pay a record $4.15 million fine for leaks at several of its wastewater ponds in southwest Pennsylvania.

The state is also beefing up its rules on impoundments, which could include mandating two liners below each waste pit. In Cecil Township, Range Resources says it will continue testing the groundwater and will remove the impoundment by next year. Janice Dumont says she won’t miss it.

This story is based on a report by Reid Frazier that aired on PRI's Living on Earth, in collaboration with the public radio program, the Allegheny Front.