Cajuns are fiercely proud of their culture, but they’re divided over the word ‘coonass’

The town of Eunice, Louisiana is one of those places that lets you know exactly where in America you are.

“I’m the owner of KBON 101.1 FM down in Cajun Country,” says Paul Marx, whose station began broadcasting music in 1997.

Much of life in so-called Cajun Country involves the French language, and Marx is fluent in what he calls Cajun French.

“We do speak different French here, a little different from Canada or France but it’s still our language — French,” he explains.

Cajun culture and the French language weren’t always so valued, though. In fact, French as a spoken language nearly disappeared, but the language and culture have made a comeback.

Artists like Jamie Bergeron & the Kickin’ Cajuns. People from around here either love or hate one of Bergeron’s songs, called “Registered Coonass.”

You can hear the song on Marx’s radio station because he likes it. Not all Cajuns do.

“I kind of got a threat by an attorney that if I continued playing the song, there’d be a lawsuit,” Marx says. “Well, that made me put the song on the playlist.”

The attorney was Warren Perrin, who threatened to file a complaint with the Federal Communications Commission if KBON kept playing the song. Since then, the station now only plays it if a listener requests it, and DJs announce it not as “Registered Coonass” but “RCA.”

Warren Perrin’s law office is 40 miles away from Eunice in Lafayette, on a street called Rue de La France. Perrin regularly sends letters to people asking them to stop using the word “coonass.”

“We ask that the person voluntarily do so and that is usually the end of it,” Perrin says. “We have not had to institute any type of formal suit or claim with the Human Rights Commission or anything like that.”

“That state agency is the only one in America existing, supported by the state of Louisiana, to promote the French language,” he says. “We have 30 French immersion schools — eminently successful. So we turned it around and we developed along the way pride in ourselves.”

Pride in your roots and the word “coonass” don’t go together, says Perrin, who’s part of a movement that has tried to stamp out the use of the word. The movement won a big victory back in 1981 when it got the Louisiana State Legislature to condemn the word as offensive. Legislators not only condemned it, they outlined the word’s etymology.

“In that concurrent resolution, the politicians in Baton Rouge wrote: The word coonass comes from the standard French word connasse, which means dirty whore or stupid person,” says local Cajun historian Shane Bernard, paraphrasing what’s in the 1981 resolution. “Cajun GIs were called this when they were in France during World War II. Anglo GIs were standing nearby, didn’t know what that meant, but said, ‘Sounds like coonass, so that’s what we’re gonna call you from now on.’”

That’s the official take on the origin of the word – a vulgar ethnic slur. But it’s not correct, Bernard says. He found a photo from the National Archives taken in April 1943 of a plane called the “Cajun Coonass.” The photo was taken before the allied invasion of France.

That’s the official take on the origin of the word – a vulgar ethnic slur. But it’s not correct, Bernard says. He found a photo from the National Archives taken in April 1943 of a plane called the “Cajun Coonass.” The photo was taken before the allied invasion of France.

“Because there were no Cajuns in France or any Americans in France until June 6, 1944, which is D-Day, that means that if the connasse theory were true, it had to have been created sometime after D-Day because you had to have Cajuns in France to be called connasses,” Bernard says. “Presumably you had to have some extended period of time for the word to morph into coonass.”

Bernard says he’s found other references to the word predating D-Day, as well. As far as he’s concerned, no one can be sure where the expression came from.

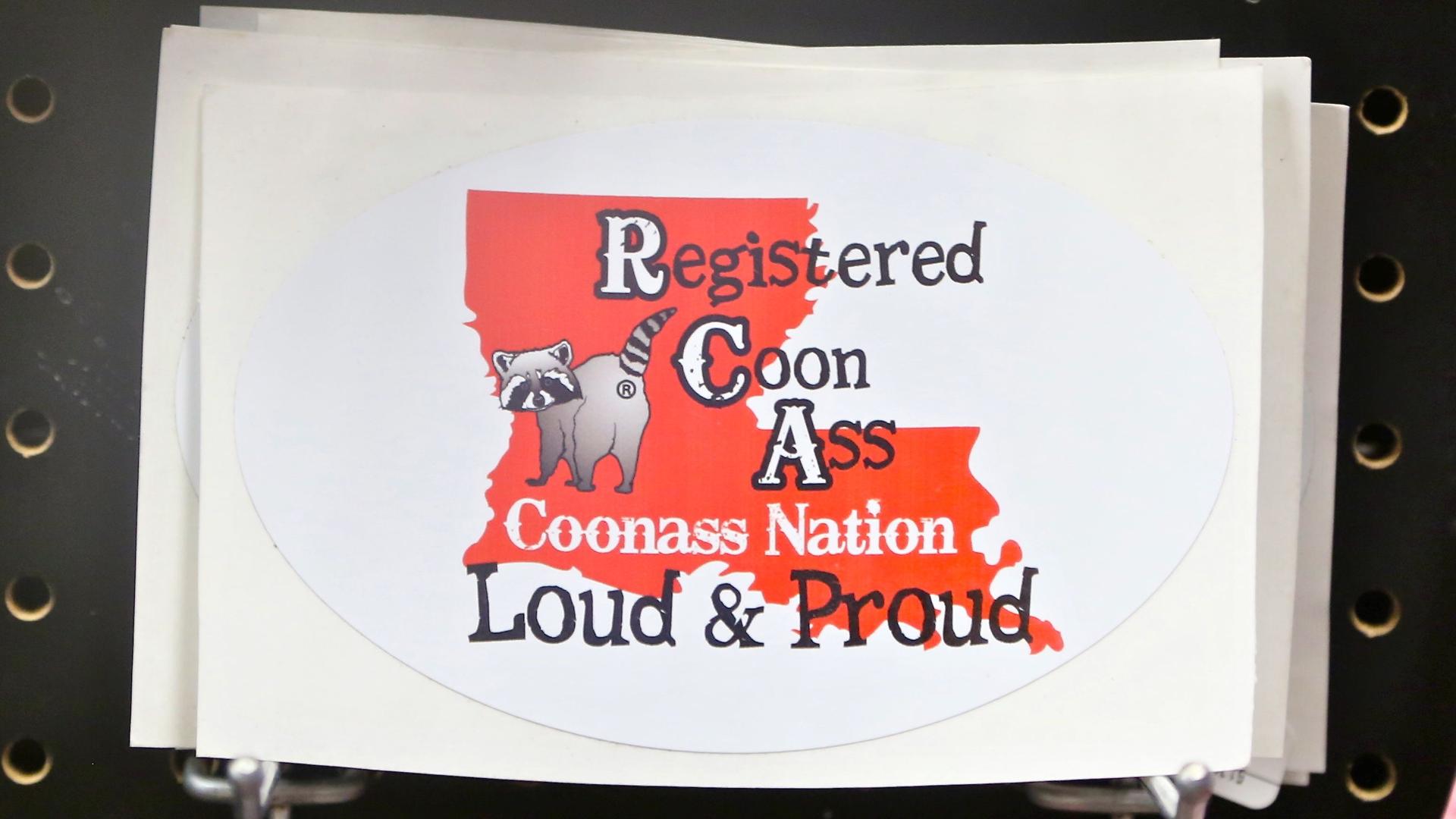

Whatever its origins, coonass isn’t a slur these days to people like Angie Sonnier. I found Sonnier on a rainy afternoon taking shelter beneath a roof of a Shop Rite store in Duson, Louisiana. The store sells bumper stickers and T-shirts with a “Registered Coonass” logo on them. Sonnier doesn’t care about tracing the history of the term “coonass.”

“If it was meant being ugly when it first came out, it’s not ugly now,” Sonnier says. “Not unless you look at it that way, and some people may. I just don’t.”

Instead, “coonass” is shorthand for her rural Cajun identity.

“I was raised, you know, running crawfish traps with my dad, and working on a farm with my dad, and doing different other things — going fishing with my family and, you know, generally doing all this type of stuff that is around here,” Sonnier says. “It’s in your blood.”

At his radio station, Marx echoes that sentiment. He remembers when speaking French at school was really frowned upon.

“‘You tried to shame us but now you know what? There are a lot of people who want to be coonasses,’” Marx says. “It’s kind of our way of slapping them in the face and saying, ‘You didn’t accomplish anything. We’re still here. You’re just an American. We’re Cajun, baby! We’re coonasses!”

It seems that, for better or for worse, the expression will be sticking around for a while.