How the US is trying to deter migrants from Central America — with music

There’s a push by Washington to send one clear message to Central American families wanting to migrate here: Don’t come.

Or, at least, don’t believe what all the smugglers promise.

“You will not get papers to allow you to stay, and you are putting yourself and your children in grave danger,” Gil Kerlikowske, head of US Customs and Border Protection, said during a press conference earlier this month.

He announced a million-dollar US government ad campaign to convince people — especially families with children — from entering the US illegally. There are radio ads, TV spots and billboards that will inundate Central America.

One jingle is about “La Bestia” — that’s the nickname for the freight train Central American migrants ride up through Mexico to the US.

The music’s upbeat, but the message isn’t. At one point the ad says, “La Bestia del sur le llama, maldito tren de la muerte,” which translates to, “They call it The Beast, damn train of death.”

It’s a song you’ll hear on the radio in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador — and it was produced in New York, for US Customs and Border Protection.

In another TV ad, a teenage boy is kissing his mother goodbye — and his uncle reads a handwritten letter from the boy, thanking him for funding his trip to the border.

“The next thing you see is the kid dead in the middle of the desert,” says Pablo Izquierdo, who runs the advertising agency in Washington that produced the ads. Izquierdo says most of the people who worked on the commercials are immigrants themselves, who know the dangers are real.

“The photographer himself was a victim of human trafficking when he first arrived in the US. So we all know someone.”

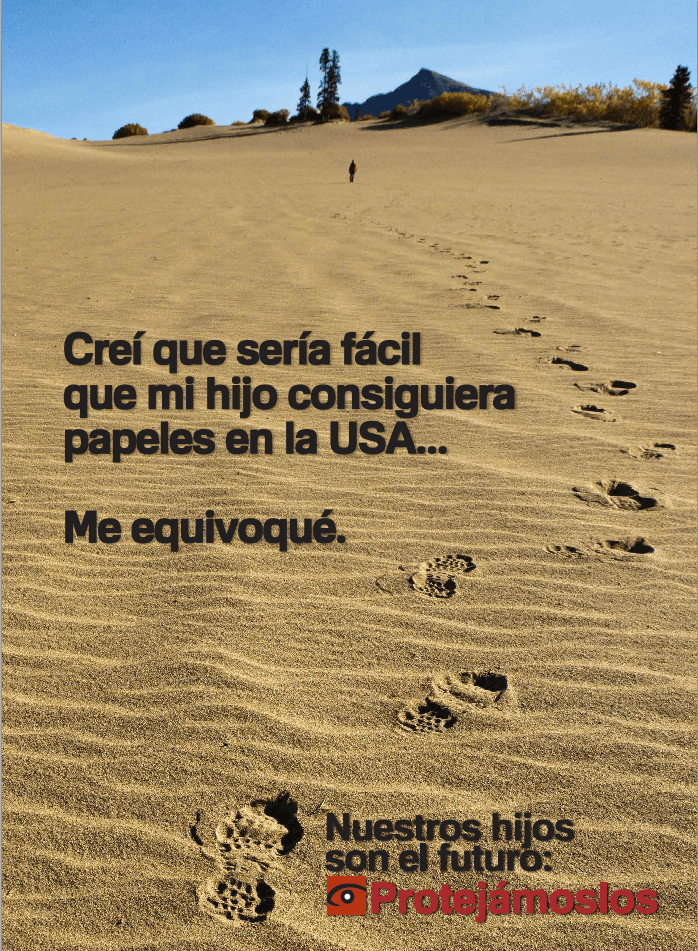

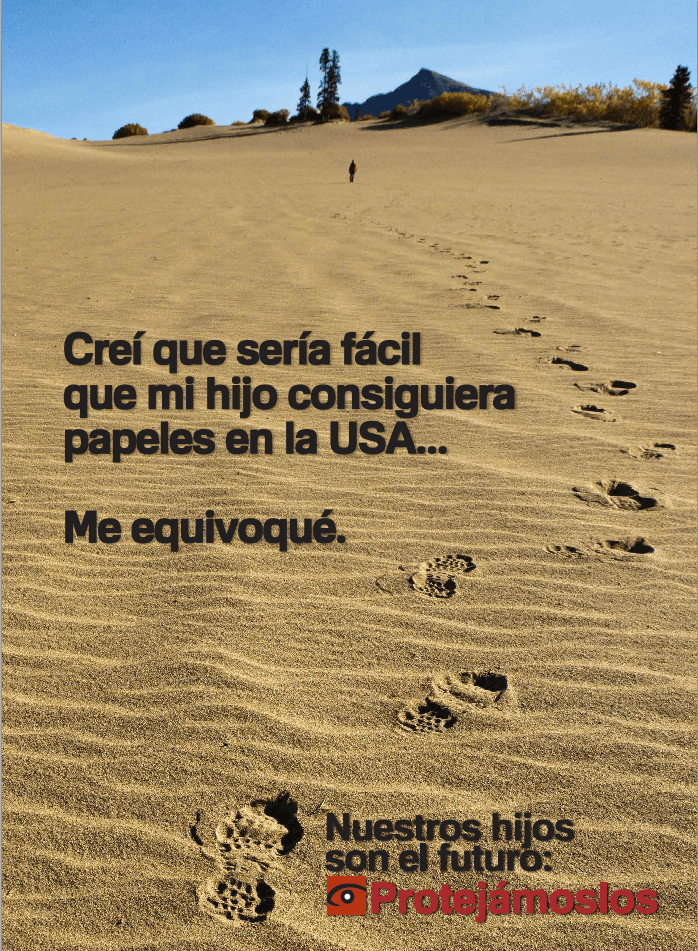

All of the ads end with a woman saying, “Que hoy sea mas facil conseguir papeles es falso,” or “It not true that getting papers is easier today.”

They say there’s no blanket US policy that lets children stay here indefinitely.

This isn’t the first time the US government has taken to the airwaves with warnings to would-be immigrants. In 2009, Izquierdo’s team produced several Migracorridos, or “immigration ballads.” They used popular, polka-style Mexican music. One ad is about two cousins walking north, across the desert.

Again, it doesn’t have a happy ending.

But while the songs were a hit on Mexican radio, they didn’t seem to do what they were meant to do: keep people from coming to the border.

“The research that we do know about is that people are very aware of the dangers, but they make the decision to try,” says Doris Meissner, former commissioner for Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) during the Clinton administration.

Now a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute in Washington, DC, Meissner says there’s no evidence that scary PR tactics, like this, change people’s minds.

“The word-of-mouth coming back from the United States is that certainly people have died along the way, but that is overridden by the very, very large numbers who make it,” Meissner says.

At Radio La Chevere in San Salvador, they’ve been running the new ad campaign for about a week.

Station manager Manuel Martínez says “The people from El Salvador have been traveling in an illegal way for about 40 years!” But he didn’t know, until now, that the US government funded the ads.

“It’s a surprise for me,” he says.

Still, Martínez says he’s fine running the ads. In fact, his station has been playing the La Bestia jingle about 10 times a day. But he doesn’t really think it’s telling Salvadorans anything new.

His station already has its own call-in show about US immigration laws, and there’s plenty of talk about how risky the journey can be. He says, in El Salvador, the danger is a matter of perspective.

“They take their chances and they make decisions and go for it. That’s what they do, because they’re in a desperate situation. The people are in danger here too. So for them it’s do or die, in many cases.”

A commercial from El Salvador:

There’s a push by Washington to send one clear message to Central American families wanting to migrate here: Don’t come.

Or, at least, don’t believe what all the smugglers promise.

“You will not get papers to allow you to stay, and you are putting yourself and your children in grave danger,” Gil Kerlikowske, head of US Customs and Border Protection, said during a press conference earlier this month.

He announced a million-dollar US government ad campaign to convince people — especially families with children — from entering the US illegally. There are radio ads, TV spots and billboards that will inundate Central America.

One jingle is about “La Bestia” — that’s the nickname for the freight train Central American migrants ride up through Mexico to the US.

The music’s upbeat, but the message isn’t. At one point the ad says, “La Bestia del sur le llama, maldito tren de la muerte,” which translates to, “They call it The Beast, damn train of death.”

It’s a song you’ll hear on the radio in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador — and it was produced in New York, for US Customs and Border Protection.

In another TV ad, a teenage boy is kissing his mother goodbye — and his uncle reads a handwritten letter from the boy, thanking him for funding his trip to the border.

“The next thing you see is the kid dead in the middle of the desert,” says Pablo Izquierdo, who runs the advertising agency in Washington that produced the ads. Izquierdo says most of the people who worked on the commercials are immigrants themselves, who know the dangers are real.

“The photographer himself was a victim of human trafficking when he first arrived in the US. So we all know someone.”

All of the ads end with a woman saying, “Que hoy sea mas facil conseguir papeles es falso,” or “It not true that getting papers is easier today.”

They say there’s no blanket US policy that lets children stay here indefinitely.

This isn’t the first time the US government has taken to the airwaves with warnings to would-be immigrants. In 2009, Izquierdo’s team produced several Migracorridos, or “immigration ballads.” They used popular, polka-style Mexican music. One ad is about two cousins walking north, across the desert.

Again, it doesn’t have a happy ending.

But while the songs were a hit on Mexican radio, they didn’t seem to do what they were meant to do: keep people from coming to the border.

“The research that we do know about is that people are very aware of the dangers, but they make the decision to try,” says Doris Meissner, former commissioner for Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) during the Clinton administration.

Now a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute in Washington, DC, Meissner says there’s no evidence that scary PR tactics, like this, change people’s minds.

“The word-of-mouth coming back from the United States is that certainly people have died along the way, but that is overridden by the very, very large numbers who make it,” Meissner says.

At Radio La Chevere in San Salvador, they’ve been running the new ad campaign for about a week.

Station manager Manuel Martínez says “The people from El Salvador have been traveling in an illegal way for about 40 years!” But he didn’t know, until now, that the US government funded the ads.

“It’s a surprise for me,” he says.

Still, Martínez says he’s fine running the ads. In fact, his station has been playing the La Bestia jingle about 10 times a day. But he doesn’t really think it’s telling Salvadorans anything new.

His station already has its own call-in show about US immigration laws, and there’s plenty of talk about how risky the journey can be. He says, in El Salvador, the danger is a matter of perspective.

“They take their chances and they make decisions and go for it. That’s what they do, because they’re in a desperate situation. The people are in danger here too. So for them it’s do or die, in many cases.”

A commercial from El Salvador:

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!