Here’s why kids — and parents — in India love the country’s school lunch program

Cooks Beddo and Bimla, make rotis (a wheat flat bread) at a government school in Bawani Khera village, in south central Haryana. The menu for the day is roti and a vegetable dish.

On July 16, 2013, a horrific thing happened in India’s northern state of Bihar. A group of young children eating a government-provided school lunch were poisoned; 23 of them died.

The food was contaminated by pesticides, a case of negligence on the part of the school principal, who was tasked with overseeing the lunch program. The principal and her husband were later charged with murder.

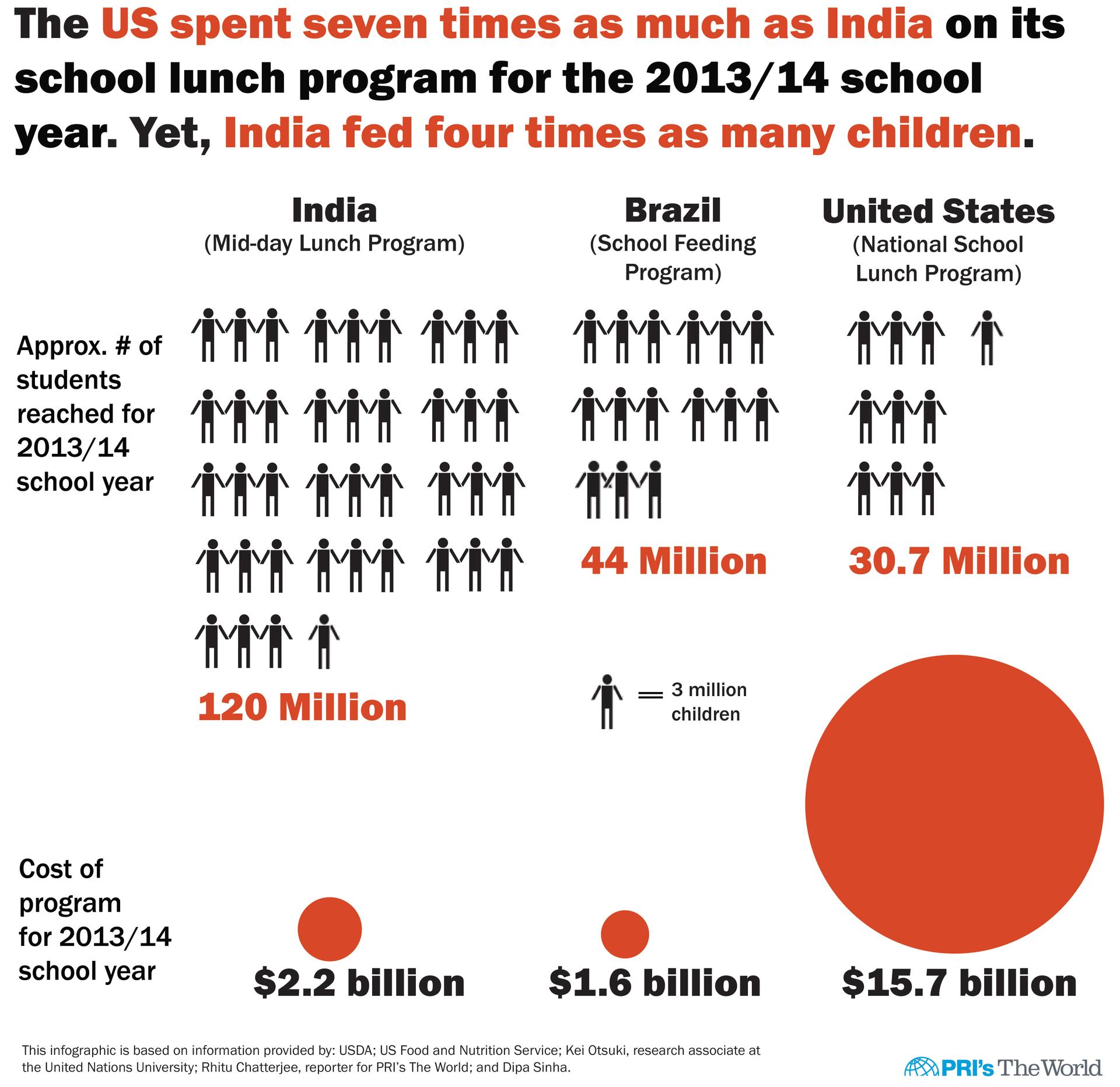

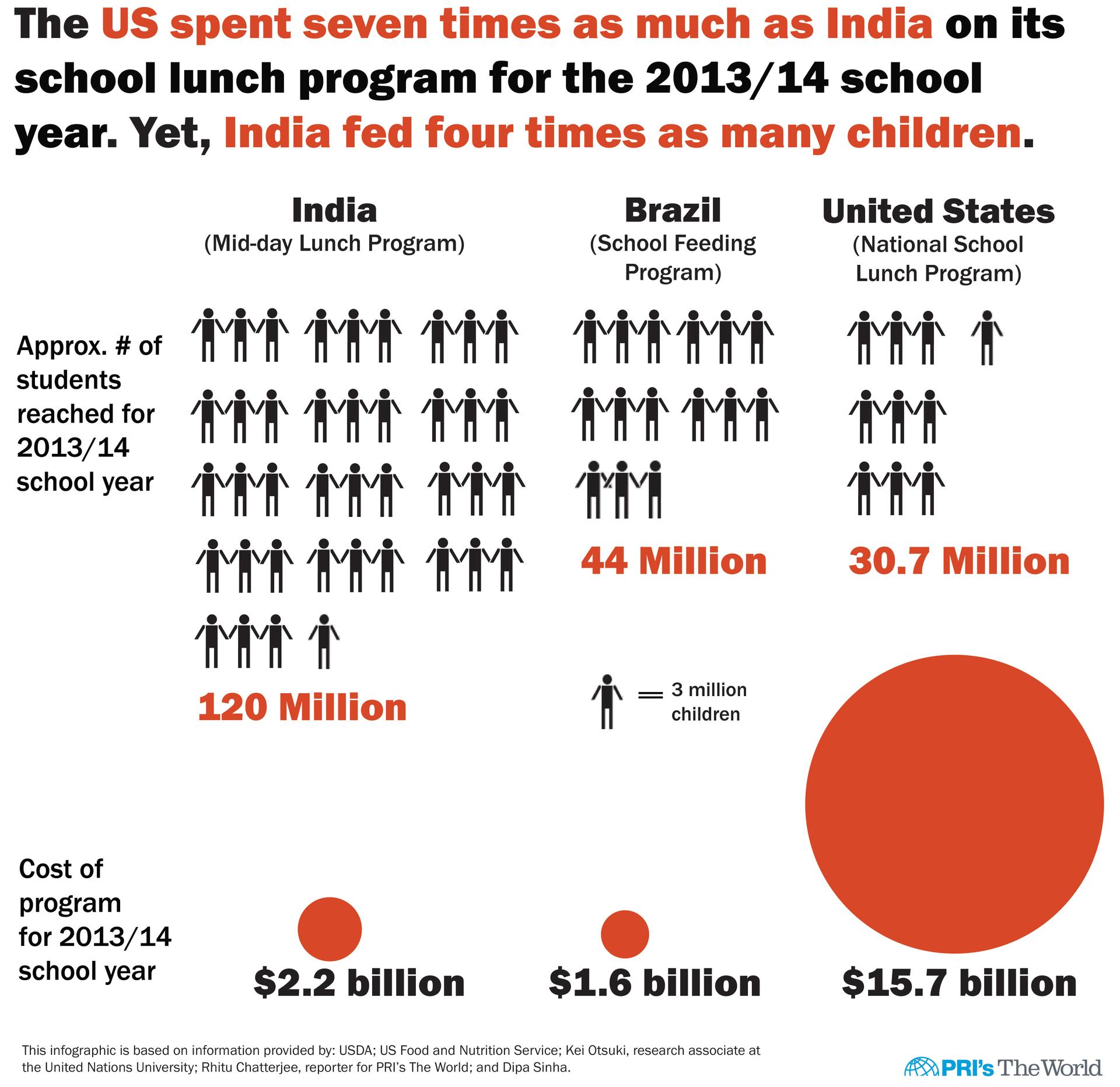

The case horrified the country. And it put a spotlight on India’s mid-day meal program, perhaps the largest free lunch program in the world. First launched in 1995, it now feeds 120 million school children across India. But it’s been criticized for corruption, inefficiency and a lack of monitoring and enforcement of standards.

The program came with lofty goals: feed hungry children and boost school enrollment. So I set off to find out if it has been successful.

I arrive around lunchtime at a local village school in Bawani Khera, in the northern state of Haryana. Students have gathered in a clearing behind one of the low-slung concrete buildings that serve as classrooms.

A group of boys distribute empty steel plates to the other students, as two women stand near two giant vats — one filled with white rice, the other with kadhi, a yellow curry made with fritters of chick pea flour.

The food is hot, cooked in the school’s own kitchen by the women serving it. The kids line up with plates in hand, and return with their food to mats laid out on the ground. The chatter dies down almost instantly as they dig into their freshly cooked food.

Most of the children I talk to say they really like the food here at school.

“The school food is cooked really well,” says Mohit, a 12-year-old girl. “I like everything we eat here, especially the kadhi with rice.”

The Indian government requires the school to serve a different meal each day of the week, and Mohit says she likes the variety.

But it’s only when I visit Mohit’s home one night that I truly understand her love for the school meal. When I arrive, her mother and aunt are preparing dinner in the open courtyard, which serves as the family’s kitchen. Her mother, Savitri, pours some chili powder on a grinding stone, adds a few cloves of garlic, and starts grinding.

She’s making a “chilli and garlic chutney,” she says. The family will eat it with roti, a wheat flatbread that’s a staple of diets in this part of the country.

Once the chutney is ready, Savitri starts kneading the dough for the rotis. This is what the family eats every night — roti and chutney, and not much else.

“We might cook vegetables once or twice a week, but only if I can find something cheap,” says Savitri. “Vegetables are too expensive these days.”

That’s why she’s so grateful for the free lunch her kids eat at school.

“They seem to cook everything there,” she says. “Sometimes it’s rice pudding, other times it’s something else. At home, it’s just this chutney and roti.”

On most days, her kids have only leftover roti with tea before heading to school, she says.

That’s a common story in this and nearby villages, says Wazir Singh, the school’s principal, who has taught in schools in this region for 30 years.

“Most kids don’t get a fresh-cooked breakfast,” he says. “For at least 90 percent of the children, their first full meal is the mid-day meal.”

It’s not very different in other parts of India, especially in some of the country’s poorest regions.

“In terms of hunger, it is very clear from what we see when we travel and from studies, that the mid-day meal makes a big contribution,” says Dipa Sinha, an economist and researcher at the Center for Equity Studies in New Delhi. She was part of a team appointed by the government to investigate implementation of the mid-day meal program across the country.

“It also has a great impact in terms of the quality of food that children are getting.”

It’s not yet possible to know if this translates into significantly better health for the children, says Sinha, because India doesn’t have a “robust school health program” that regularly monitors students’ health.

But the first rigorous study to investigate this over a period of time suggests that the program’s impact could be profound.

The study, part of an ongoing project called Young Lives, is tracking 2,000 children over 15 years.

“It’s usually believed that once a child becomes malnourished, it’s almost impossible to catch up,” Sinha says. “But this Young Lives study shows that catch-up growth is also made possible by the mid-day meal scheme.”

There is also some evidence that the meals make students do better at school, she adds.

But long before the health impact of the free lunches became apparent, it became clear the program was having another impact.

“The first dramatic effect of the program was a big increase in school enrollment and school attendance,” says Jean Dreze, an economist and food rights activist who’s also advised the Indian government on this and other social programs.

“If you look at school registers at the time, you can see that there was a big jump in class one (first grade) around the time of the introduction of the mid-day meal program.”

Studies have shown that the increase in enrollment and attendance is more pronounced among girls, and among children from the poorest communities. These are children who might have been kept out of school to help their parents with housework or earning a livelihood.

The free lunch program seems to help the poorest families send their kids to school, says Dreze, and it makes the children want to go to school.

“The mid-day meal helps to self-motivate the children. They go to school on their own, because they feel like going there,” Dreze adds.

That's why many educators all over the country support the program — despite its shortcomings.

“Given my 30 years of teaching experience in this region, I believe there’s a huge need for the mid-day meal,” says Singh, the principal of the village school in Bawani Khera.

“And being a teacher, I say that we should also serve breakfast in school.”

Rhitu Chatterjee’s Mid-Day Meal reports were produced with help from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

On July 16, 2013, a horrific thing happened in India’s northern state of Bihar. A group of young children eating a government-provided school lunch were poisoned; 23 of them died.

The food was contaminated by pesticides, a case of negligence on the part of the school principal, who was tasked with overseeing the lunch program. The principal and her husband were later charged with murder.

The case horrified the country. And it put a spotlight on India’s mid-day meal program, perhaps the largest free lunch program in the world. First launched in 1995, it now feeds 120 million school children across India. But it’s been criticized for corruption, inefficiency and a lack of monitoring and enforcement of standards.

The program came with lofty goals: feed hungry children and boost school enrollment. So I set off to find out if it has been successful.

I arrive around lunchtime at a local village school in Bawani Khera, in the northern state of Haryana. Students have gathered in a clearing behind one of the low-slung concrete buildings that serve as classrooms.

A group of boys distribute empty steel plates to the other students, as two women stand near two giant vats — one filled with white rice, the other with kadhi, a yellow curry made with fritters of chick pea flour.

The food is hot, cooked in the school’s own kitchen by the women serving it. The kids line up with plates in hand, and return with their food to mats laid out on the ground. The chatter dies down almost instantly as they dig into their freshly cooked food.

Most of the children I talk to say they really like the food here at school.

“The school food is cooked really well,” says Mohit, a 12-year-old girl. “I like everything we eat here, especially the kadhi with rice.”

The Indian government requires the school to serve a different meal each day of the week, and Mohit says she likes the variety.

But it’s only when I visit Mohit’s home one night that I truly understand her love for the school meal. When I arrive, her mother and aunt are preparing dinner in the open courtyard, which serves as the family’s kitchen. Her mother, Savitri, pours some chili powder on a grinding stone, adds a few cloves of garlic, and starts grinding.

She’s making a “chilli and garlic chutney,” she says. The family will eat it with roti, a wheat flatbread that’s a staple of diets in this part of the country.

Once the chutney is ready, Savitri starts kneading the dough for the rotis. This is what the family eats every night — roti and chutney, and not much else.

“We might cook vegetables once or twice a week, but only if I can find something cheap,” says Savitri. “Vegetables are too expensive these days.”

That’s why she’s so grateful for the free lunch her kids eat at school.

“They seem to cook everything there,” she says. “Sometimes it’s rice pudding, other times it’s something else. At home, it’s just this chutney and roti.”

On most days, her kids have only leftover roti with tea before heading to school, she says.

That’s a common story in this and nearby villages, says Wazir Singh, the school’s principal, who has taught in schools in this region for 30 years.

“Most kids don’t get a fresh-cooked breakfast,” he says. “For at least 90 percent of the children, their first full meal is the mid-day meal.”

It’s not very different in other parts of India, especially in some of the country’s poorest regions.

“In terms of hunger, it is very clear from what we see when we travel and from studies, that the mid-day meal makes a big contribution,” says Dipa Sinha, an economist and researcher at the Center for Equity Studies in New Delhi. She was part of a team appointed by the government to investigate implementation of the mid-day meal program across the country.

“It also has a great impact in terms of the quality of food that children are getting.”

It’s not yet possible to know if this translates into significantly better health for the children, says Sinha, because India doesn’t have a “robust school health program” that regularly monitors students’ health.

But the first rigorous study to investigate this over a period of time suggests that the program’s impact could be profound.

The study, part of an ongoing project called Young Lives, is tracking 2,000 children over 15 years.

“It’s usually believed that once a child becomes malnourished, it’s almost impossible to catch up,” Sinha says. “But this Young Lives study shows that catch-up growth is also made possible by the mid-day meal scheme.”

There is also some evidence that the meals make students do better at school, she adds.

But long before the health impact of the free lunches became apparent, it became clear the program was having another impact.

“The first dramatic effect of the program was a big increase in school enrollment and school attendance,” says Jean Dreze, an economist and food rights activist who’s also advised the Indian government on this and other social programs.

“If you look at school registers at the time, you can see that there was a big jump in class one (first grade) around the time of the introduction of the mid-day meal program.”

Studies have shown that the increase in enrollment and attendance is more pronounced among girls, and among children from the poorest communities. These are children who might have been kept out of school to help their parents with housework or earning a livelihood.

The free lunch program seems to help the poorest families send their kids to school, says Dreze, and it makes the children want to go to school.

“The mid-day meal helps to self-motivate the children. They go to school on their own, because they feel like going there,” Dreze adds.

That's why many educators all over the country support the program — despite its shortcomings.

“Given my 30 years of teaching experience in this region, I believe there’s a huge need for the mid-day meal,” says Singh, the principal of the village school in Bawani Khera.

“And being a teacher, I say that we should also serve breakfast in school.”

Rhitu Chatterjee’s Mid-Day Meal reports were produced with help from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!