Rigo Tovar: an Appreciation of a Mexican Pop Star

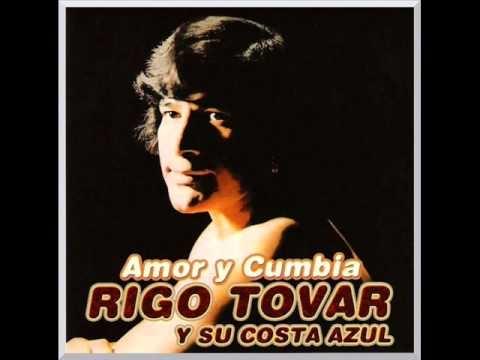

Rigo Tovar CD Cover

Rigo Tovar was born in Matamoros, the Mexican border city on the other side of Brownsville, Texas. His father was Mexican and his mother Tejana. In his early twenties, Rigo and his older brothers moved to Houston in search of a better life. In Houston, he founded the group Costa Azul.

In 1971, an executive from a local record label offered to pay for his first studio recording, Mi Matamoros Querido, an homage to his hometown.

This was one of the first songs by Rigo Tovar I heard on the radio. I was twelve.

In the mid-70s, Rigo Tovar released what I consider his best album, Amor y Cumbia.

The record helped propel him to rock star status. And he played it to the hilt, complete with long hair, leather pants, and dark sunglasses–modeled after his beloved Black Sabbath and Queen.

One of his classic cumbias from that album is “El Testamento.”

Rigo Tovar had a gift for quirky, over-the-top lyrics. I mean, who else could think of leaving a will with verses such as these:

To Asunción, I’m leaving my heart,

To María, all my happiness

A million hugs to Concepción

To Theresa, all my sadness

To faithful Leticia, all my caresses

And to the cruel Amparo, nothing for being unfaithful…

With this song and dozens of others played on the radio, Rigo Tovar became Mexico’s biggest tropical music artist. At one point, radio stations across the country even had the “Rigo Tovar Radio Hour” so they could attract a big audience.

And according to some estimates, more than 400,000 people attended his concert in Monterrey in 1979. Just imagine that crowd dancing–and singing–along to one of his biggest hits, a hilarious cumbia titled “La Sirenita” (the Little Mermaid).

I have to mention that my brother, Quintín, was a huge Rigo fan. He would buy all his records. And of course, we learned how to dance to Rigo’s cumbias at weddings, Quince Años and baptisms.

But I have to say, Rigo wasn’t liked by everyone. Some people in our circle of friends considered him in bad taste. They felt his music and songs were cheesy and his persona too campy.

His appeal was biggest among the working class. Because he was one of them. He talked like them and looked like them.

The middle class was smitten with the disco craze–and every other type of American music. Rigo was not cool to them. But he was to us.

Today, looking back at Rigo Tovar’s career, I think his most important contribution to Mexican music was something I call “Cumbia del desamor” or “Cumbia of unrequited love.” You see, before Rigo Tovar, Mexicans could only sing the blues with rancheras, sung by a mariachi band, next to a bottle of tequila.

But what better therapy could there be to cure the wounds of love but a cumbia dance?

Imagine you’re depressed and broken-hearted and a radio DJ puts on this very cool tune by Rigo Tovar called “I’m still waiting for her.”

It’s time to dance the blues away.