Scientists urge CDC to revise lead exposure level deemed safe in children

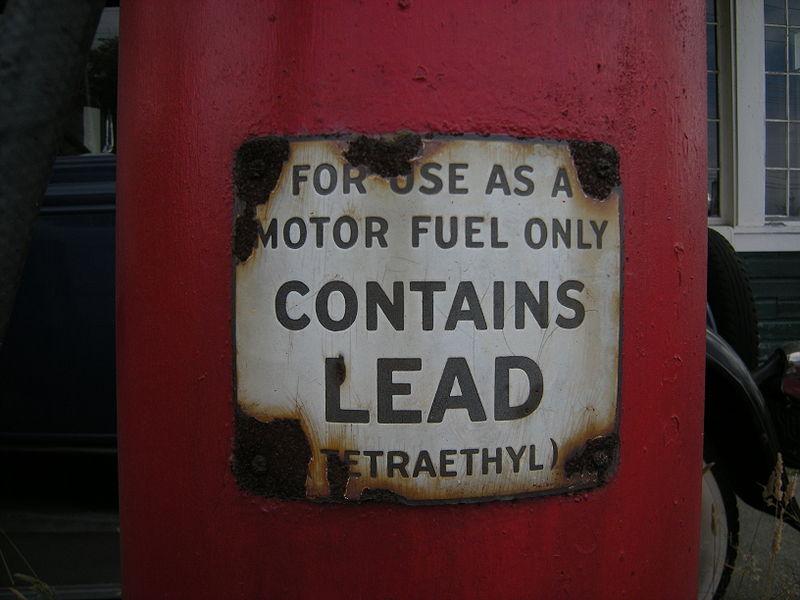

Automobile fuel used to be a major source of lead, until federal standards banned its use. Still, lead levels that were once thought safe seem to cause neurological damage, so a panel has urged the safe level be lowered. (Photo by Joe Mabel via Wikimedia

A group of scientists say the federal standard on lead exposure in children is too high and must be lowered.

Kim Dietrich, director of epidemiology at the University of Cincinnati Department of Environmental Health, is on the panel of scientific advisors who are urging the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to act quickly to decrease lead exposure for children.

“There have been studies, epidemiological studies that show there are effects well below the previous level of concern of 10-15 micrograms per deciliter,” he said.

Rather, Dietrich says, the standard should be as low as 5 micrograms per deciliter. When he first started researching lead poisoning, he said few American children had levels below 10 micrograms per deciliter. Now, 31 years later, most children do have exposure levels lower than that. But they’re still seeing averse effects for those at the high end of currently allowable levels.

“My studies generally involve children that have blood lead concentrations above ten,” he said. “They have lower volumes of cortical gray matter in the frontal lobes which are associated with judgment, reasoning, anticipation of consequences — what we call the executive functions.”

Those same kids have been linked to higher rates of juvenile delinquency and adult criminality.

Dietrich said the only totally safe level of lead exposure would be zero, but that’s unrealistic, given the centuries of lead exposure in the environment. For example, even today, most lead exposure can be traced back to lead paint, which was banned in the 1970s. Because lead makes paint durable, a lot of lead paint persists on buildings and in the soil around buildings, Dietrich said.

“It’s the lead dust in these homes that’s the real problem because it sloughs off the wall over time, gets into the dust, and even if you clean it up, it will appear again several weeks later because it continues to come off the walls,” he explained.

If the CDC agrees with the panels recommendations, some 500,000 American children would have lead levels higher than the level considered safe. It would essentially double the number who are currently viewed to exceed safe levels.

“One of the things that the committee tried to do was to put the emphasis on the environment rather than the child as a barometer of the environment – that we need to eliminate lead hazards in the first place,” Dietrich said.