New novel puts comedic spin on terrorist attack

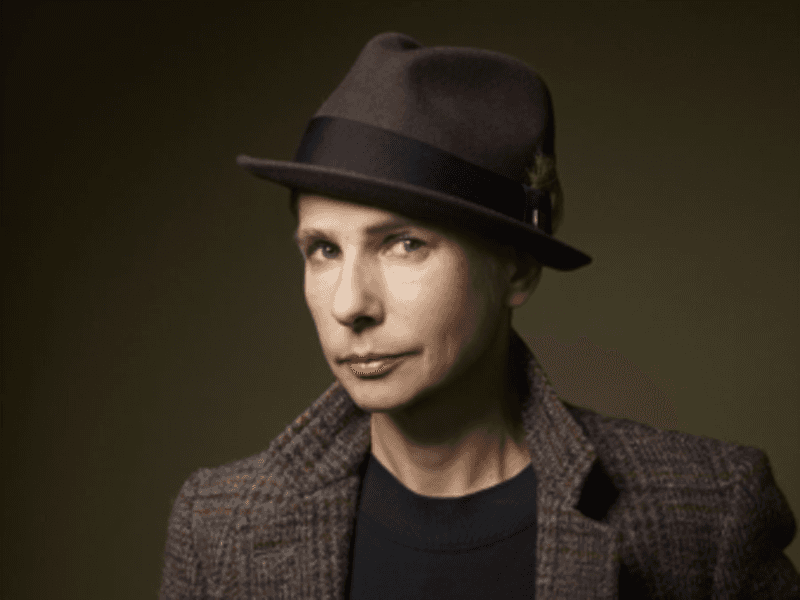

Lionel Shriver published The New Republic, a comedic look at modern-day terrorism. (Photo by Suki Dhanda/Reuters.)

Edgar, a successful corporate lawyer, rashly quits his job to become a journalist. He’s rescued from hack freelancing with a big break: a stringer assignment in a place called Barba, a (fictional) province of Portugal.

A shadowy anti-immigrant terrorist group wants Barba to secede from Portugal (to become a new republic) and has claimed responsibility for dozens of bombings all over Europe. Edgar joins a cluster of American reporters waiting, all too eagerly, for the next bombing to provide them with the stories they need to keep their jobs.

That’s the premise of Lionel Shriver’s new novel, The New Republic. It’s maybe in a genre by itself: a comedy about terrorism.

“When I finished the novel in 1998,” she said, “I did try to publish it, and I just couldn’t stir any interest. Publishing this book immediately after 9/11 would have seemed like jumping on the bandwagon … and furthermore it would have seemed tasteless. Because it’s funny. I really had to wait until now to publish this book.”

Violence and its causes are a preoccupation of Shriver’s, whose 2003 novel We Need to Talk About Kevin is about the mother of a Columbine-like killer. It became last year’s movie starring Tilda Swinton. And The New Republic, despite its dark humor, takes terror seriously.

Shriver, who was born in North Carolina, moved to Belfast during the last years of the violent Troubles that rocked Northern Ireland.

“One thing we don’t appreciate is that terrorism works. I saw it work close up,” she said. “The people who were bombing mainland Britain and assassinating political opponents are running the place now.”

The media, she said, plays a role in this process.

“When violence occurs it seems as if it’s worth covering. The trouble is that journalists act as magnifiers for terrorists. Without the press, terrorism doesn’t have the same effect. We’re really between a rock and a hard place on this one.”

Still, The New Republic is not ultimately about foreign policy, but about human nature. The protagonist, Edgar, carries a deep emotional wound as a “former fat kid” who has been mocked and bullied.

“I had buck teeth when I was a kid,” Shriver said. “I know what it’s like to be mocked, rather low down on the totem pole. People who are attractive don’t realize how nice people are to them because they look pretty. And they have no idea how other people are treated.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?