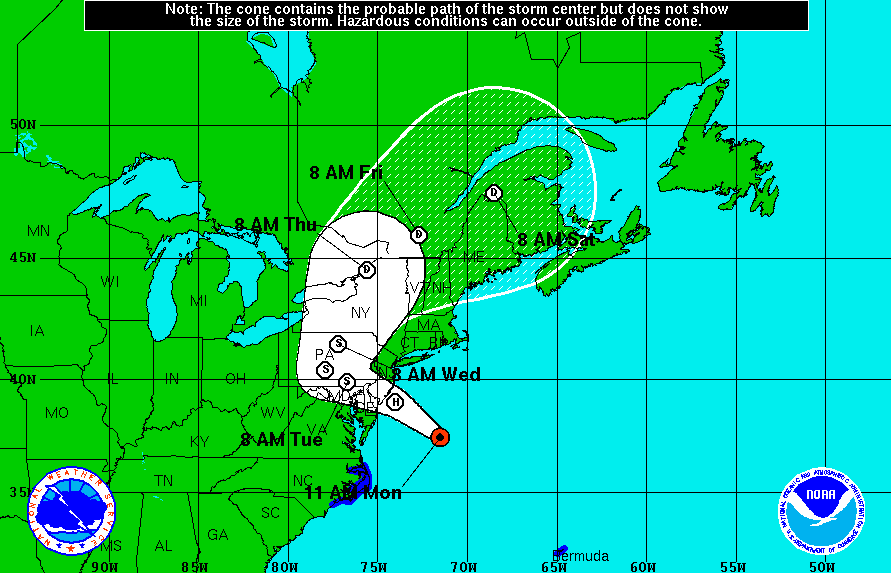

MAP: Officials urge caution, warn of danger as Hurricane Sandy becomes ‘Frankenstorm’

Hurricane Sandy is expected to make landfall in New Jersey Monday night or Tuesday morning.

Schools are closed, offices are shuttered and flood waters are rising along much of the eastern seaboard as Hurricane Sandy bears down on the American northeast.

“Do things indoors. It doesn’t mean you can’t go out to eat, doesn’t mean you can’t go out, it’s just more dangerous to do so,” New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg implored in a press conference Monday afternoon.

President Barack Obama praised state and local officials for their preparations and urged citizens to listen to local leaders when they called for evacuations, and when they told them to stay indoors. And for anyone who wasn’t listening, he had a particular message.

“You’re putting first responders in danger,” he said.

The circumstances that combined to create what has been dubbed Frankenstorm are rare, if not downright unique. Hurricane Sandy has continued to strengthen as it moved northeast because of a rare confluence of events: a low pressure trough surging east, a high pressure ridge lodged over Greenland and Canada, driving the hurricane to take an extremely unusual westward turn and a pulse of Arctic cold air moving south from Canada.

All that has combined to create a storm that could batter New York City, New Jersey, Delaware and Washington, D.C., with winds of almost 100 mph, dropping upwards of six inches of rain across the Mid-Atlantic and, perhaps, leaving more than a foot of snow in West Virginia and other areas.

And that doesn’t even account for the storm surge, which is already pushing water into Red Hook in Brooklyn, and inundated Atlantic City. It’s the largest storm surge, predicted to be as more than 9 feet and perhaps as much as 13 feet, in 100 years of weather history along the New Jersey and New York coasts, said Jeff Masters, the meteorology director and co-founder of the forecasting service Weather Underground.

He says just once in recorded history, some 150 years, has a hurricane ever hit New Jersey.

Masters, a former hurricane hunter with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, called this a 1-in-500 year event.

“We know that climate change is affecting our weather patterns,” he said, “but whether it’s affecting this particular one, we can’t tell at this point.”

But these seemingly weird weather events are becoming sufficiently common over the past few years that, Masters says, there has to be some relationship with the weird weather in general — if not any one particular event.