As economic recession marches on in Spain ‘Robin Hood’ character galvanizes poor, unemployed

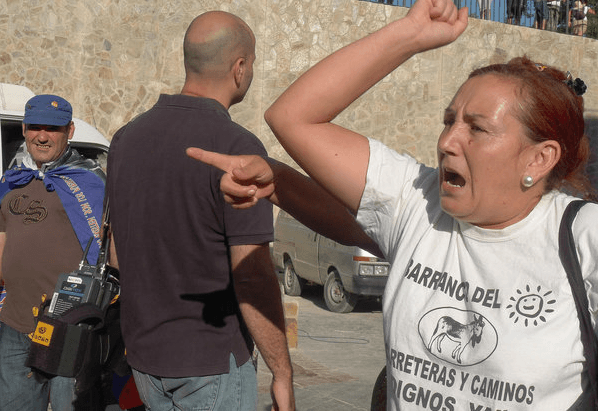

A protester in Casabermeja prepares for what will be a sometimes-tense march to Malaga, in protest of increased taxes and continued unemployment. (Photo by Gerry Hadden.)

Sparks from a farmer’s fire caused yet another massive blaze in Spain last week. Some 8,000 acres burned near the southern beach town of Malaga.

But Spanish authorities are just as worried about a different spark in the region. This one’s a politician. His name is Juan Manuel Sanchez Gordillo — or, as he’s been dubbed of late, Spain’s Robin Hood.

Gordillo has been leading marches across southern Spain to protest budget cuts and a giant bank bailout due from Brussels. Along the way he and his followers have been stealing food from supermarkets to give to the poor.

If Gordillo is Spain’s Robin Hood, his followers would be his merry men, and women.

See more photos from the Spanish protest march at TheWorld.org.

On an early morning this week, about 250 mostly out-of-work laborers gathered in a tiny whitewashed village called Casabermeja, 20 miles inland from Malaga. A stocky, former construction worker named Jose Maria Bozuna had just arrived, walking stick in hand.

He said he lost his job three years ago, and lives off about $600 a month in unemployment. He says he and his sons have taken to scavenging the countryside for olives and beans.

“They keep trying to squeeze money out of us,” he said, referring to a slew of government tax hikes meant to lower the deficit. “But there’s nothing left to squeeze. They’re going to have to shoot us to shut us up.”

This workers march is the fifth this summer. The protesters set off down a quiet interstate, past olive orchards and pine forests. They brandished Union flags and Soviet flags, even flags with Che Guevara’s face on them.

In terms of size, it’s not the most impressive march in Spain’s history.

But there were nearly as many police on hand as marchers. Three different forces patrolled the line, on motorcycles and in riot vans. A police helicopter even swooped past.

Authorities weren’t so worried about the marches themselves: it’s the deliberate acts of civil disobedience.

A workers march last month led to a raid on a supermarket. Some 50 activists filled shopping carts with food, left without paying, and distributed the items to poor families.

The stunt was designed to draw attention. It worked. The march’s leader, Gordillo, a communist mayor from a nearby village, was quickly dubbed Robin Hood in the press.

Since then Gordillo has gotten so much attention that he’s fallen ill from exhaustion. He made only a brief appearance during this leg of the Malaga march, to call on the government to save poor people before it saves banks, and to insist his protest movement is non violent.

“We’re hoping that social action is enough to change things,” he said. “That’s the ideal. It’s worked before, for example in India.”

Such rhetoric has led to further comparisons — this time to Gandhi — which only makes Gordillo’s movement more popular. Everywhere the marchers went, townsfolk came out to cheer them along.

Along one stretch of road, an unemployed mason named Antonio Jurado, holding his infant daughter in his arms, came out to encourage the marchers.

“I’m a lefty unto death,” he said. “The current government only helps the rich.”

With unemployment at 25 percent in Spain, many young are turning to Gordillo, at least in Andalucía. Gordillo’s ultimate goal is to see his modest marches spread nationwide. His demands seem to be resonating.

As the protestors made camp near a pass high above Malaga, a spokesman for the Andalusian Workers Union, Diego Cañamera, rattled off what the movement wants. The list is long. And revolutionary.

“A guaranteed minimum wage for everyone,” he said. “Public works to create jobs. The redistribution of public lands for farming.”

The movement, he says, is also against evictions of families who can’t pay their mortgages, and recent, drastic cuts in government spending on education and healthcare.

Cañamera admits these ideas are utopian. And achieving them herculean, despite the movement’s warm reception in the streets.

“To expose our politicians and bankers for what they are,” he said, “people need to be in the street with strength, and conviction, but peacefully.”

The hope, he said, is to influence Spain’s next elections.

When the march arrived in Malaga Tuesday, the moment everyone had been bracing for arrived. And it was anything but peaceful.

A group of protestors stormed in and took over a local savings bank.

Protestors outside the bank scuffled with police. One police officer was injured, a handful of marchers were arrested. It’s unclear who provoked whom, but the incident illustrates the difficulties in organizing non-violent protests.

Like the Occupy Movement in the United States, this Robin Hood rebellion has attracted all sorts of followers, from idealistic reformers to anarchists.

And Tuesday’s temporary bank takeover shows just how popular these marches have become. Tens of thousands of angry Malaga residents flooded streets in support of the workers, chanting “send the bankers to jail.”