Division developing between main Islamist parties in Egypt

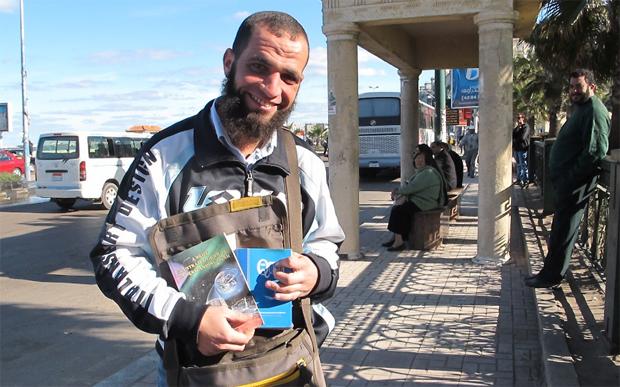

Ahmed Aadli tries to hand out religious books to tourists in downtown Alexandria. (Photo by Ben Gilbert.)

Egyptian Ahmed Aadli, 30, was at a crossroads recently.

He had a steady job working as a dive instructor with a German tour company at Egypt’s Sharm El Sheikh resort. But he wasn’t satisfied.

“I was looking for inner peace, and I thought it would be by book, or girlfriend, or wife, or good work,” Aadli said. “But actually I found inner peace, in the creator. Direct connection.”

Aadli found peace and happiness in religion. And he hopes to spread the message. He now sports a long, scraggly beard and volunteers with the Conveying the Islamic Message Society.

Every morning from 8 to 10 he cheerfully distributes Islamic literature to tourists in front of Alexandria’s main hotel.

He’s not especially political, but he voted in Egypt’s elections. And he chose the Islamic parties: the Muslim Brotherhood, and their main competitors, the Salafis, because he said they “are like two faces of one coin.”

Many Egyptians likely felt the same way at the beginning of elections here, candidates for the Salafis and the Muslim Brotherhood were devout Muslims who want to implement Sharia-based law in Egypt. And for most, that’s a good thing.

But Muslim Brotherhood officials don’t want to be lumped in with Salafis as “Islamists”.

“There are the Muslim Brotherhood, and there are Salafists. This is the point which we don’t like. Don’t take us with their mistakes,” said Mohamed Soudan, the foreign relations secretary for the Brotherhood in Alexandria.

Soudan said the Salafis’ mistakes are narrowly interpreting Islam, and expecting that all Egyptian Muslims should share their beliefs. And he calls them political amateurs. That’s definitely not an accusation leveled against the Muslim Brotherhood: it was founded in Egypt in 1928, under the banner: “Islam is the answer.”

They have been accused of violent acts in the past, like the attempted assassination of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser in the 1950’s. There was a massive crackdown and the group was banned. It took years to recover. They renounced the use of violence long ago.

Despite the ban, the Muslim Brotherhood has become a hugely powerful force in Egypt, in large part because of the social programs they’ve run — geared toward both rich and poor.

The Muslim Brotherhood was finally permitted to register as a political organization — the Freedom and Justice party — last year. Soudan said the party is moderate, and advocates one key thing.

“We believe in democracy, 100 percent. And we are hungry for a democracy in Egypt,” he said.

And that is one of the biggest differences between the people who the west calls simply “Islamists.”

Many Salafis say God’s law, not man’s, should rule, calling into question their belief in democracy. And the Salafis are more strict and dogmatic, while the Muslim Brotherhood is more diverse, and in general more inclusive, open to compromise and politically pragmatic.

Soudan criticized the Salafis’ focus on things like booze and bikinis at tourist resorts.

“These are small things. And this country’s run likes this for 60 years. You can’t change this in one second. You need to teach the people. You need to feed the 40 percent of the Egyptian people who are suffering from poverty. And then fix the streets, fix the economy, we have a problem with the economy. Start with this,” he said.

But it’s not like the Brotherhood is liberal. They do want an Islamic state, just in a slower and more moderate way. With alcohol, for instance, Soudan said he’d rather it not be sold, but he recognizes that it’s big business — for producers as well as the tourist industry.

The Brotherhood is more moderate when it comes to women’s rights — their education, and role in society. The group has accepted in theory that a woman or a Coptic Christian should legally be allowed to be president in Egypt, although neither is likely to happen. Women and Copts also ran on the Brotherhood’s ticket in Parliamentary elections, and won.

Mahmoud Hegazi, is one of those who voted in Alexandria for some of the Brotherhood’s candidates. He’s a devout Muslim, and Egyptian-American. He lived part of his life in New Jersey. He now lives here and works with the “Conveying the Islamic Message Society.” Hegazi said he voted for the Brotherhood’s candidates because he thinks that their brand of Islam — moderate but devout — will make Egypt a better place.

“These people, actually, they seek refuge in the religion because they know through implementing the religion of Islam in this country people actually will be fairly treated,” he said. “They will be treated with justice. They will be given equal opportunities in jobs, in political positions and so on.”

Still, some secular Egyptians fear their moderate message is a smokescreen, and that the brotherhood will aim to make society more conservative by bringing the Islamic message to Egyptians through domination of education and religious foundations.

Hossam Baghat, the director of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights in Cairo, is not happy about the success of the Brotherhood, but felt it was a long time coming.

“It’s a painful but necessary part of the process,” Baghat said. “It could prove beneficial in the long run, in our transition toward democracy. It’s a battle we’ve put off for 70 years — the role of religion in politics. The place of the religious parties in a future polity. And now is the time to have it. Because with power there will come accountability and responsibility. And it’s time that the Islamist activists start answering tough questions they’ve been relieved from answering over the past few decades of persecution.”

The biggest test comes now on two fronts for the Muslim Brotherhood. The first is how far they will go in challenging the current military rulers’ attempts to hold onto power.

The other question revolves around their main competitor for constituents, the Salafis: Will the Brotherhood be pulled to the right by the hardline Salafis, or might the Brotherhood help moderate the Salafis’ hardline ideas?