Climate scientist links Arctic melting to U.S. weather fluctuations

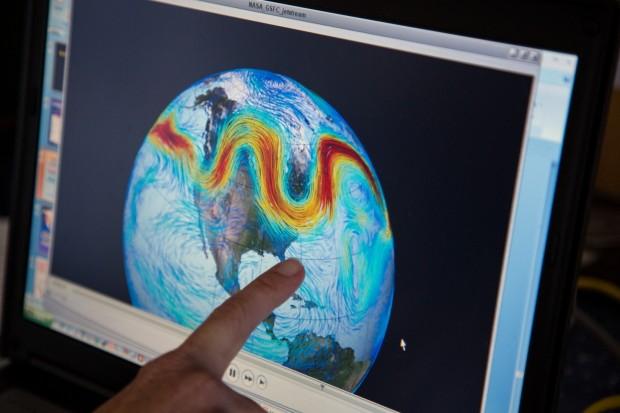

This image from a NASA time-lapse animation shows how, over time, the southward and northward waves of the jet stream have grown deeper and move more slowly across the mid latitudes as melting sea ice warms the Arctic. (Photo: Sam Eaton)

David Robinson knows just about everything there is to know about climate change.

But starting a borrowed chainsaw is another thing altogether.

“Ahh, this doesn’t look good,” Robinson said as he struggles with the cord. “This isn’t going to start.”

But it does finally start, and he and his son set to carving up a giant oak tree that fell in his son’s yard during Hurricane Sandy. He says chainsaws are one of the most common sounds around this part of New Jersey these days.

“I grew up in New Jersey, and my over 50 years in this state, nothing had come close to this in terms of tree damage,” he said.

View a slideshow from this story at TheWorld.org.

But Robinson says things could have been much worse, despite the scores of deaths across the region and a price tag running into the tens of billions of dollars. If Sandy’s winds had been just twenty miles per hour stronger, he says, parts of New Jersey would’ve been without power for months.

“Your entire electric grid would have to be rebuilt. And quite likely you’d see an exodus, at least a temporary exodus, of people from the state.”

Robinson’s concern is more than that of the average New Jersey resident. He’s the state climatologist. And he says increasingly extreme weather all across the world is testing the ability for even the richest nations to recover.

Here in New Jersey he says the weather isn’t just breaking records, it’s blowing right past them.

“We’ve had 21 straight months of above average temps in New Jersey and the mid-Atlantic region,” Robinson said. “And then we’ve seen major storms. It was a year to the day before Sandy made landfall that central and northern New Jersey up into southern New England had an unprecedented October snowstorm.”

Climate scientists avoid blaming any single weather event like Sandy on global warming. But many say that climate change may well have played an important role in Sandy’s destruction, as well as other recent extreme weather events.

It’s not just that global warming is contributing to rising sea levels and warmer ocean temperatures off the northeast. There’s also growing evidence that weather in places across the United States is being affected by rapid warming far to the north, in the Arctic.

Climatologist Jennifer Francis of New Jersey’s Rutgers University says that warming in the Arctic may be altering the jet stream, which impacts weather patterns across the northern hemisphere.

The jet stream is largely created by temperature differences between the Arctic and areas farther south, Francis says.

“So if you warm the Arctic more than areas farther south, which is what’s happening, there’s no doubt about that, then the jet stream should be weaker, because the temperature difference is smaller,” she said. “And that’s exactly what we see.”

Francis pulls up a time-lapse animation of the jet stream’s waves on her computer. It starts out showing waves of air moving quickly across North America.

“But then there’s this period where the waves get much bigger,” she said. “We’re moving toward an increased tendency for the jet stream to get into these big, wavy patterns that tend to move more slowly. … So the weather that’s associated with them on the surface, either the storms or the high pressure areas, whatever it is, are going to stick around longer at a given location.”

That means a greater chance of ordinary weather becoming extreme events like last summer’s drought and heat wave in the American Midwest or last winter’s cold snap that killed more than 800 people in Europe.

“You can look at almost any extreme event of the type that I described,” Francis said. “Look at the atmospheric pattern that was associated with it, and almost every single time it’s because there was one of these big swings in the jet stream.”

Hurricane Sandy was no different. Cold Arctic air coming from one of these large dips in the jet stream to the west strengthened the storm, while a huge high pressure system to the north blocked Sandy’s movement over the Atlantic and drove it directly toward the east coast.

Francis co-authored a study on these kinds of changes in a peer reviewed journal last spring, before this summer’s record Arctic meltdown and before Sandy. But the science hasn’t yet been widely accepted.

Gavin Schmidt, with NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, is among the climate scientists who aren’t yet convinced of the connection between a warming Arctic and extreme weather events.

Schmidt says global weather is a particularly complicated system.

“We can find patterns in rich systems all the time,” he said. “They lead us into lots of interesting pathways for research. But for every 20 patterns that we think we see in a very complicated noisy flow, only one of them is going to actually turn out to be something that is a robust thing that we can use for predictions.”

Schmidt says findings like Francis’s need to be plugged into climate models and compared to other results. He says it’s too early to know whether there’s really a cause and effect link between the warming Arctic and weird weather to the south.

But Schmidt says there is definitely “something funky” going on.

“We’re increasing the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere beyond what they’ve been naturally in 800,000 years, maybe millions of years,” he said. “That’s a huge perturbation to the system. Everything in the system (is) being affected by that.”

But figuring out exactly how these complex systems are reacting to that disturbance takes time.

It’s a challenge Francis is well aware of as she walks along a beach down the road from her home near Buzzards Bay, in Massachusetts.

The area was spared from the deadly tidal surge that wiped out so much of New York and New Jersey, but Sandy still left its mark here. Francis points out a spot where the storm’s water came right up to the edge of a building near the shore.

Today, though, the same jet stream that shot Sandy into the east coast is bringing clear skies and unseasonably warm temperatures from the northwest.

“It’s the good weather side of the waves in the jet stream,” she said.

Francis spends an awful lot of time crunching data in the lab, but she says she’s also starting to see the impacts of what she’s studying right here where she lives.

“There’s a lot of realism to what’s happening today and I think I’m not the only one that’s sensing that,” she said. “This is something that’s happening before our very eyes. It’s not something that we don’t have to worry about for another generation or two. And the fact that there’s this link to a place that’s so far away and so different from here — you know, the Arctic, people don’t think of it being relevant to them. But in fact it really is.”

The trick for scientists like Francis is teasing out just how powerful those changes in the Arctic are becoming, and how likely they are to contribute to more events like Sandy — or worse — in the years ahead.