Swaziland Chief Fought With Allied Forces in WWII

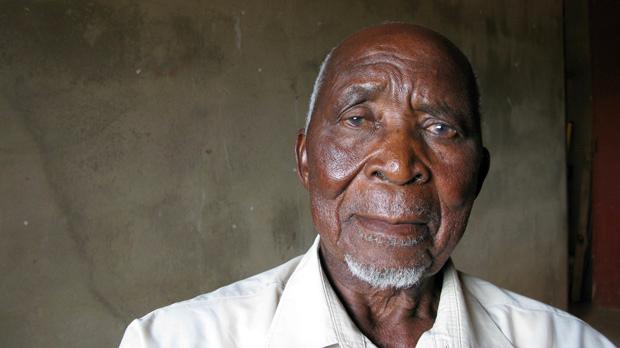

Chief Mnikwa Dlamini of Hhelehhele, in the Hhohho region of northern Swaziland. Now 88-years-old, Chief Mnikwa fought alongside Allied forces in Europe and north Africa during the Second World War. (Photo: Alex Gallafent)

The stock characters of the second world war have become ingrained in our culture down the decades. But there’s always room for a surprise.

Mnikwa Dlamini, for example, is the current chief of Hhelehhele, a rural area in the north of the country. He’s also an 88-year-old veteran of the war in Europe.

Swaziland is a small country in southern Africa. It gained its independence in 1968.

Before that it was ruled by the British, and before them the Boers. When war came to Europe, the British came knocking.

“All our life here in Swaziland was under British control,” remembers Chief Mnikwa. “It was mostly okay because the British and us had a good relationship. They at least treated us better than the Boers did.”

“We first heard in 1939 that the Germans were fighting with the British. They only said that they used to be friends with the Germans, and then after a while the Germans had started fighting them.”

As the war drew on, the then-King of Swaziland, Sobhuza, agreed to gather volunteers to fight as part of the Allied forces. In exchange, he extracted promises from the British of greater autonomy for his country in the future. But the young Mnikwa, not yet a chief, had his own reasons for signing up.

“The reason why I was eager to go to war was because there were rumors in my home that I might become the next chief,” he recalls.

“I said it’s better that I go to die. It was never in me. I said it’s better that I should go there because the way to heaven I would definitely find there.”

He didn’t want to be the chief because there would be ‘too much noise’.

So Mnikwa and a few thousand other young Swazis registered with the British authorities. They were given boots, khaki uniforms, the works.

In late 1941 Mnikwa was shipped off for training near the Suez Canal. He was soon fighting in the deserts of Libya, and then in Italy.

“[Benito] Mussolini, who was a politician, was friendly with Hitler. We then had to fight the Italians as well.”

“There were lots of bombs around. And they used to have bombs planted around in the ground, and you would touch some of them and they would go off, and people would die.”

Along the way, Mnikwa met soldiers from all parts of the world, including the United States. He remembers that they were “not people who liked to talk to other people very much. They would talk every now and then, but most of the time they kept to themselves.”

The war ended, and Mnikwa traveled back to southern Africa. He spent some time in Johannesburg, trying to avoid the inevitable. But eventually he returned to Hhelehhele to take up his responsibilities.

“I then realized that I can’t just do my own will. Clearly it was God’s wish that I should live.”

There are people who go to war out of a moral obligation, but perhaps not that many. Most sign up to pay their bills, or to pay for college. Others go because they’re told to.

Mnikwa Dlamini, the chief of Hhelehhele, a rural area in the north of Swaziland went because he didn’t want to be a chief.

This story was produced with assistance from the International Reporting Project. Thanks to Vusumnotfo, Bob Forrester and Mlungisi Dlamini.