Storm expert says climate change may have played a big role in Typhoon Haiyan after all

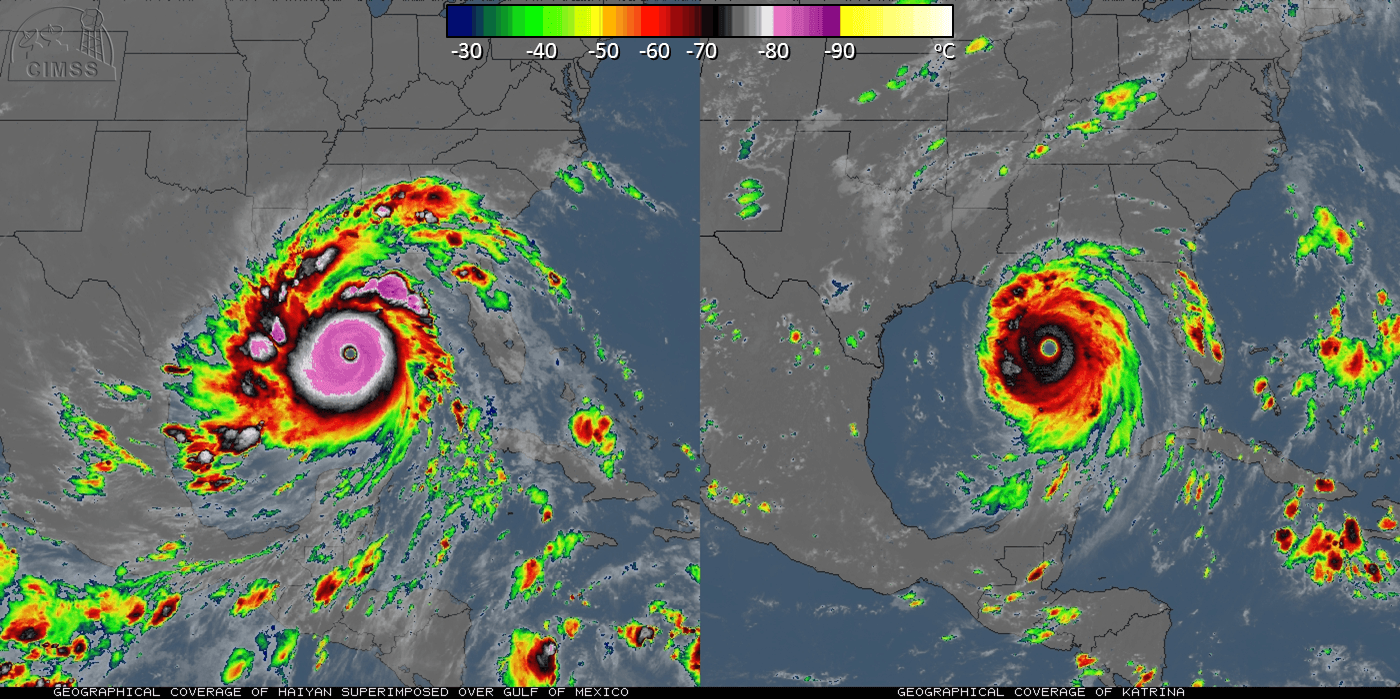

(L) Satellite image of Typhoon Haiyan, superimposed on the spot in the Gulf of Mexico where Hurricane Katrina reached its maximum strength in 2005, and (R) actual satellite image of Katrina. Colors correspond to temperatures in Celsius. Temperatures at the tops of tropical storms roughly correspond to storm intensity, with colder temperatures above generally indicating a more intense storm below.

We've heard that climate change likely played a very minor role in the havoc that typhoon Haiyan wrought on the Philippines.

And that’s what we reported in the days right after the massive storm blasted across the country in early November, killing thousands, leaving tens of thousands homeless and destroying huge swaths of the country's transportation and public services infrastructure.

But in the couple of weeks since then, our primary source for that story has taken a deeper look at the storm and has found that climate change may have played a much bigger role in its damage than he initially thought.

Soon after Haiyan hit, Kerry Emanuel, an atmospheric scientist at MIT and one of the world’s leading experts on tropical storms, told The World that the influence of climate change was probably small.

“Certainly it played a role in one obvious respect,” Emanuel said at the time, “in that sea levels are elevated, and so the storm surge, which is a big killer… was higher than it would’ve been. Beyond that, it’s difficult, and perhaps impossible, to attribute one particular event to any kind of climate signal, whether it’s global warming or el Niño or some other phenomenon.”

Since then, though, Emanuel has been taking a deeper look at the storm and has updated his analysis.

While his basic conclusion remains — that we can’t blame the formation of any particular weather event on climate change — he’s put a much finer point on it.

Emanuel and his colleagues took a computer model they use to forecast the wind speeds in a storm like Haiyan and ran it with the thermodynamic conditions that were present 30 years ago, in the 1980s, before the warming of the last few decades. They compared it to the model using current conditions.

“And when we do that,” Emanuel tells The World, “we find that the wind speeds are about ten pecent larger now.”

That’s because warmer surface temperatures essentially provide more fuel for tropical storms.

Emanuel says the destructive potential of a windstorm goes up quickly with wind speed, “so that really corresponds to something like 30 to 40% more damage than the same exact event might've done had it occurred in the thermal environment of the 1980s.”

So does that mean climate change was responsible for this much greater damage?

Not necessarily, Emanuel says, but it’s suspect #1.

“The next step in that is to say, why was the thermal environment more favourable?” Emanuel says. “We haven't really done that, but the first culprit we look for is the global warming phenomenon.”

With the benefit of a couple of weeks of analysis, Emanuel has also reached another striking conclusion: As awful as the impact of Haiyan was on the Philippines, if it had hit the United States instead, “it would've been perhaps a worse disaster.”

Emanuel says that’s because the U.S. is much less well-prepared than the Philippines, when it comes to extraordinary storms.

“The Philippines gets hit by five, six, seven, eight typhoons year, and [occasionally] a category five storm [like Haiyan]… They’re used to it,” Emanuel told The World. “We get hurricanes, and sometimes very strong hurricanes, but not as regularly and not quite at the magnitude that we see in the Pacific… So if we had a Haiyan go into the United States, it would be mayhem.”

Part of the reason, Emanuel says, is that for years the U.S. has subsidized and encouraged people to live and build in flood zones and other risky places. He says the Philippines, on the other hand, understands the risks better. They’re “hardened for typhoons.”

The tragedy in the Philippines, he says, is that the government actually did a reasonable job evacuating people. “A lot of the people killed were in evacuation shelters,” Emanuel says. “They just weren't strong enough” to stand up to a massive storm like Haiyan.

One of the tools Emanuel and his colleagues used to evaluate the likely impact of Haiyan had it hit the U.S. was a simple visual experiment. They took a satellite image of Haiyan, color-coded for temperatures at the top of the storm, and superimposed it on the Gulf of Mexico, in the position where Hurricane Katrina was when it was at its peak in 2005.

The comparison shows how much larger Haiyan was than Katrina.

That's important, Emanuel says, because a larger storm creates a bigger storm surge, “which is what really kills people. It’s like a tsunami in the middle of a hurricane.”

The temperatures of the storm's cloud tops also show that Haiyan was stronger than Katrina at its peak magnitude.

As awful as the storm’s impact was on the Philippines, Emanuel says the U.S. and the entire world can learn valuable lessons from Haiyan.

“Whenever there's a disaster," he says, “however horrible it is, it's an opportunity for us to learn from it … about climate change or about resiliency, how to build buildings, how to prevent people from moving into risky places, if possible.”

As for his own lessons from Haiyan? Emanuel says it is that, when you have a truly exceptional event, “almost nothing you might've done in preparation for it is going to work, it's just too far out of human experience."

“It's going to be a tragedy,” Emanuel says. “And how we avoid that is something we all need to put our heads together and think about.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!