Carlos Rafael runs a shop in downtown Guatemala City that sells pop culture mugs, stickers and keychains. He said he’s been feeling hopeful ever since Guatemala’s new president, Bernardo Arévalo, was sworn in over a month ago.

“We all believe that changes will come,” he said. “Because the country is so tired from the same traditional political class. We aren’t a poor country. We have money. The problem is that it’s stolen.”

Arévalo has promised to fix problems like corruption under his watch.

Arévalo is the son of the country’s first democratic president, Juan José Arévalo, who ushered in what’s known as the country’s “Guatemalan Spring,” which included new reforms and rights to benefit the country’s poor, working class and Indigenous communities.

During Bernardo Arévalo’s presidential campaign, he promised a renewal of his father’s Guatemalan Spring.

Tackling corruption is first on the agenda.

On Wednesday, he presented the team that will make up the National Anti-Corruption Commission. The 12-person group is composed half of government officials and half of representatives of civil society, the private sector and Indigenous groups.

“We want to eradicate corruption from the institutional and collective culture in the country … to generate systemic and sustainable change.”

“We want to eradicate corruption from the institutional and collective culture in the country,” Arévalo said, “to generate systemic and sustainable change.”

Arévalo’s anti-corruption team is charged with supervising the use of public money and identifying and dismantling the patterns of corruption in the country.

But they have their work cut out for them.

“You have very high expectations for this government. But I’m not convinced that they have all the necessary tools for this government to succeed.”

“You have very high expectations for this government. But I’m not convinced that they have all the necessary tools for this government to succeed,” said Pamela Ruiz, a Guatemala-based analyst for the nongovernmental organization International Crisis Group.

“How are you going to tackle corruption when you don’t have someone in the attorney general’s office to prosecute corruption cases, or that will slow down cases, at best?”

That attorney general is Consuelo Porras — the president’s leading adversary. She led the fight to block Arévalo from the presidency last year through numerous lawsuits and legal measures.

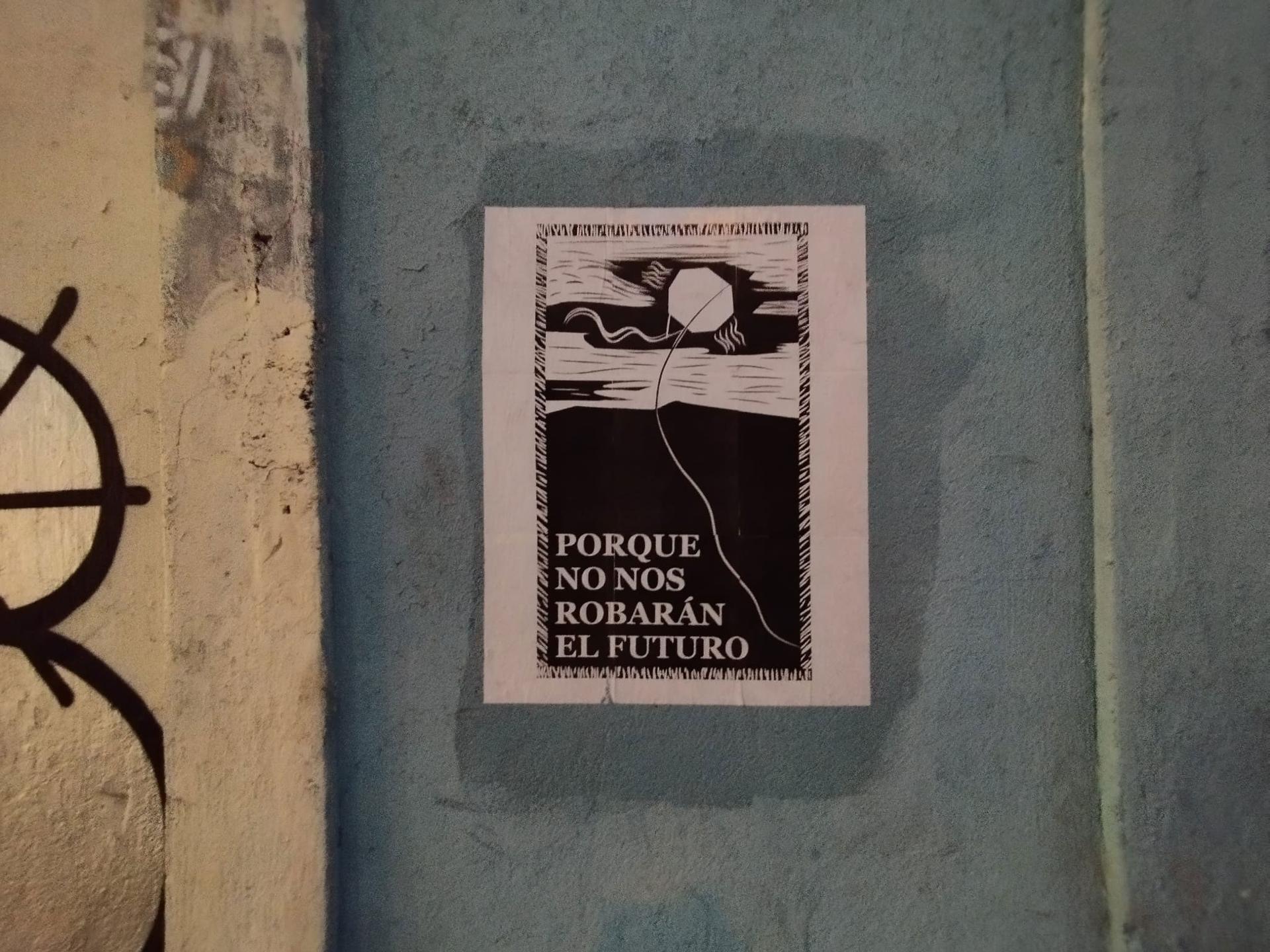

Last October, Indigenous peoples led a nationwide strike in response, launching a 106-day protest camp in front of the public prosecutor’s office. There, they defended Arévalo and called for Attorney General Porras to resign. They accused her of attempting a coup d’etat and fighting for the interests of the corrupt elites trying to hold onto power.

Porras has since been sanctioned by the European Union and the United States for undermining the country’s democracy. But, she says she is not going anywhere.

“I will not resign,” she said in January, in an official declaration posted online after Arévalo was inaugurated.

Her term lasts until 2026. She has continued to be antagonistic toward the Arévalo government.

Most of the protest signs and graffiti on the walls in front of Porras’ office have been cleared. But one vibrant mural remains, across the street, that depicts people in Indigenous dress, raising their arms in defiance. The words in Spanish above it read: “Guatemala, you will flourish.”

On Thursday, the Arévalo government filed a complaint in the Guatemalan courts asking for Porras’ immunity as attorney general to be withdrawn, so she can be criminally charged for an alleged “breach of duties.”

But she is not the only opposition.

In Congress this week, lawmakers with the country’s largest conservative party Vamos announced legal actions against President Arévelo’s party, Semilla, which holds about 15% of congressional seats.

The former president of Guatemala’s National Congress, Allan Rodríguez, says Congress doesn’t even recognize the Semilla party. “They are cheaters, they are fraudulent,” he said, “and it’s been proven once again.”

“It’s unfortunate that these corrupt elites still have so much power.”

“It’s unfortunate that these corrupt elites still have so much power,” said George Mason University political scientist Jo-Marie Burt. And I am afraid that they are going to distract the new government’s attention by forcing them to just fight for survival so they won’t be able to get any actual important policies put in place.”

But Arévalo’s government is taking positive steps forward. The president has put more police on the streets to fight crime. Government watchdogs say the Arévalo administration has taken measures to make the government more transparent.

“We value that the government has good intentions and an open-door practice that allows us to do our work better,” said Zuleth Muñoz, the country’s environmental ombudsman at Guatemala’s Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office. “The attention to our interviews. Access to information. Participation in meetings.”

But for some of those on the streets, change is taking too long.

“We hoped change would be faster.”

“It’s really slow,” said Areli Ramirez, an employee at a children’s store at a mall in an upscale Guatemala City neighborhood. “I feel that not too many things have been done yet. It’s been two months. We hoped change would be faster.”

Analyst Pamela Ruiz said people need to understand that the new administration is starting off at ground zero.

“Some of the ministers are coming out saying that we’ve received institutions that are barely functioning, if functioning at all,” she said. “So, to expect this administration to achieve many things, will be to set people up for failure and disillusionment.”

That is clearly something Arévalo and his team hope to avoid.