Adherents of Sarnaism try to preserve their identity and culture by pushing for more recognition of their faith in India

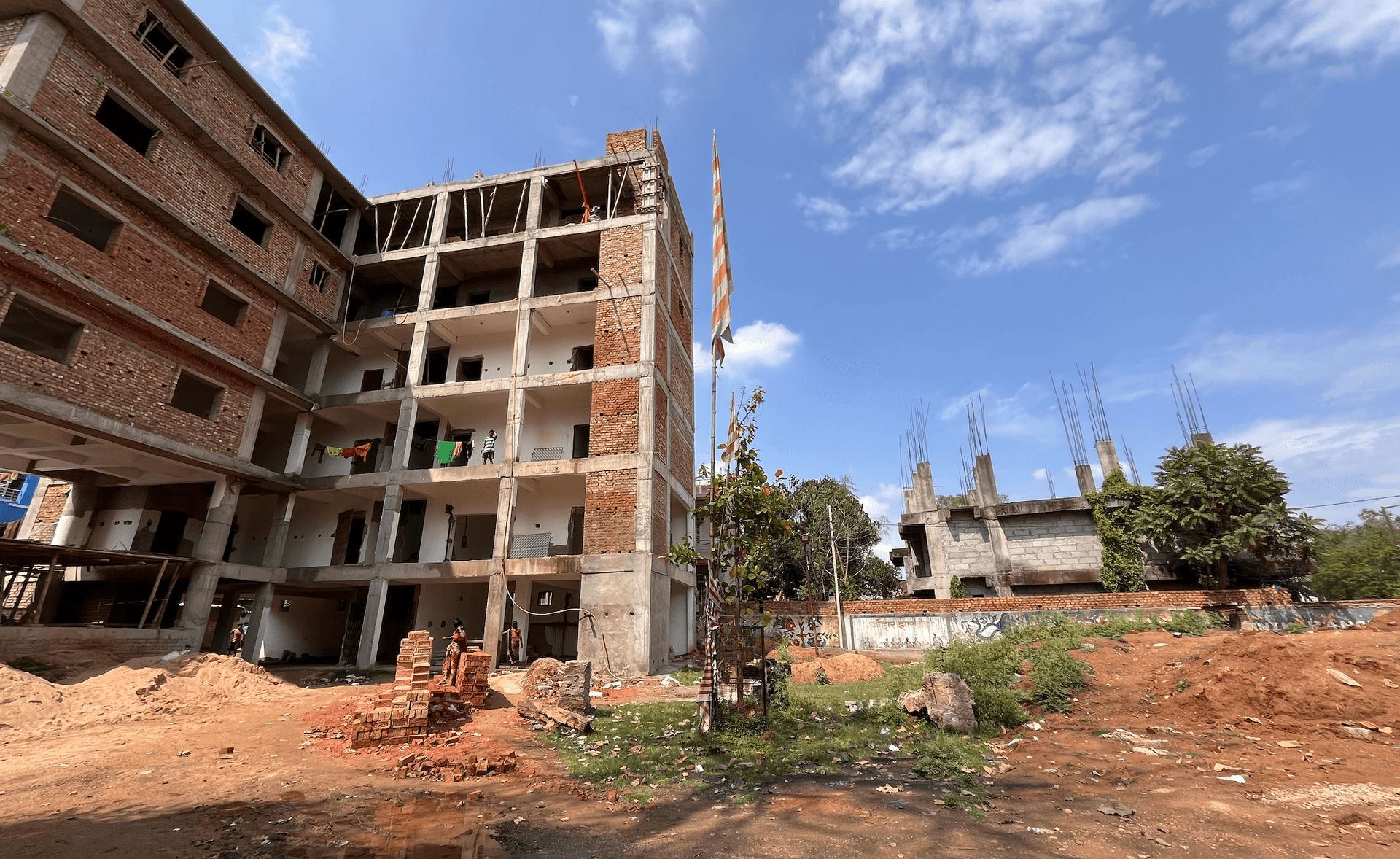

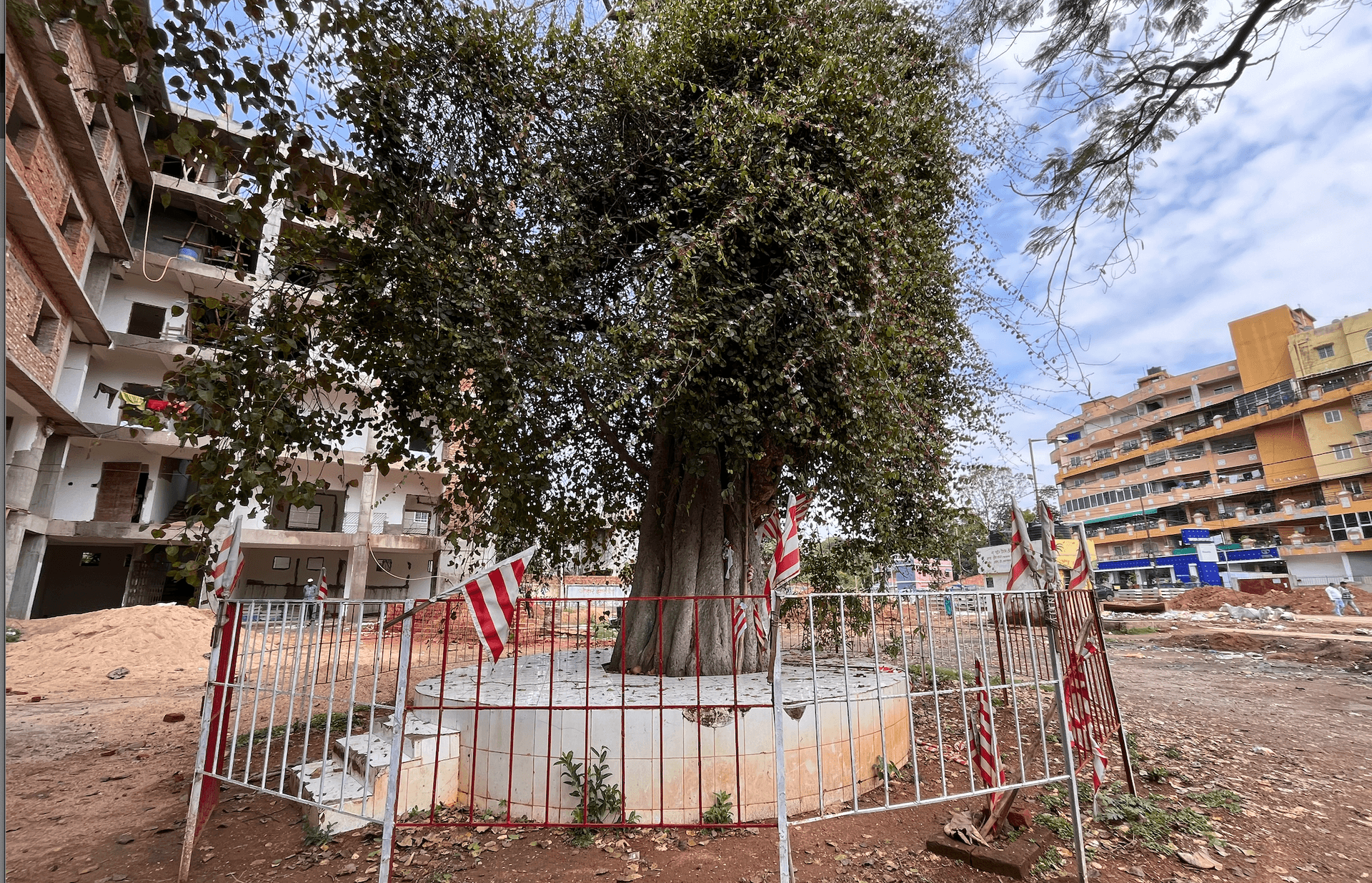

A short walk from the railway station in Ranchi, the capital of the eastern Indian state of Jharkhand, there is a unique place of worship. It doesn’t feature any structure or iconography — just a tree surrounded by a metal fence to protect it.

It is a sacred grove where members of India’s tribal community go to pay their respects.

India is home to 104 million Indigenous people, a diverse group consisting of hundreds of tribes collectively known by the umbrella term “Adivasi.” They are believed to be the original inhabitants of India and make up roughly 9% of the country’s population, according to the most recent census conducted in 2011. Today, they are fighting for visibility in a country where they are a minority.

Adivasis pray to nature and don’t believe in idol worship or the concept of heaven and hell. Their main festival, Sarhul, marks the new year and falls in spring. Crowds of men and women dressed in red and white flood the streets, dancing together to the beats of drums.

Worshippers throng sacred groves that dot the landscape of eastern and central India, home to a sizable Indigenous population. In Jharkhand, the sacred groves most commonly feature a Sal tree, a deciduous variety with thick leaves native to South Asia. Tribal people believe that their gods and spirits reside in these trees, says Anjana Singh, who teaches history at Ranchi University.

“[Adivasis] are spirit worshippers, they are ancestor worshippers. They believe in magic, they believe in spells,” Singh said. “And they have [a] whole lot of structure around their religion, which makes it completely distinct.”

Tribal religion is commonly known as Sarnaism but it is not one of India’s official religions. The Indian census, a mammoth exercise usually conducted every 10 years that shapes economic and social policy, categorizes Indians into six faiths: Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, Sikhism, Buddhism and Jainism. Those who don’t fall under these are grouped as “other religions and persuasions,” which is how many tribal people have been characterized for decades.

Preserving identity and culture

Tribal groups want to change that. They say recognizing their faith is integral to preserving Adivasi identity and culture. For over a decade, tribal groups have been calling for a separate Sarna religious code — official recognition like what other major religions in India enjoy.

The absence of religious recognition leaves tribal people vulnerable, said Salkhan Murmu, a tribal leader and former member of parliament. “Our people, most of them are illiterate or innocent (simple-minded). And with pressure, manipulation, until we get this religious identity, our people will be forced to embrace Hindu[ism], Islam, Christianity, etc.,” he said.

In the past, foreign missionaries converted large numbers of Indigenous people to Christianity. And now, India’s Hindu nationalists are trying to convince tribals that they are Hindus.

“Hinduism and Sarnaism are the same. We both worship nature,” KK Gupta, a BJP leader from Jharkhand, said in 2022. Some Hindu nationalists blame Christian missionaries for creating a rift between Hindus and Sarna followers and insist that Sarnaism stems from Hinduism.

But that notion isn’t popular in the tribal pocket of Angada, about an hour’s drive from Ranchi city. On a rainy afternoon, a group of tribal women had gathered and discussed their faith.

Pinky Debi, a petite young woman, described how she offers rice and water at sacred groves. “We, Adivasis, are the guardians of the forest,” she said with pride.

Her friend Chandmani Bando Oraon said that during British colonial times, the census had a separate column for tribal religion, but it was discontinued in 1951 after India’s independence. “So, where do we go now, to Hinduism?” she asked rhetorically.

“Adivasi traditions are totally different from Hindu traditions, yet the government is trying to count us as Hindus.”

“Adivasi traditions are totally different from Hindu traditions,” Debi added, “yet the government is trying to count us as Hindus.”

Singh, from Ranchi University, said that Hindu nationalists are trying to subsume tribal people into the larger Hindu identity as part of an effort to project India as a Hindu nation. “It is vote-bank politics.”

To do so, the Hindu right wing is engaging in cultural appropriation, she explained. They’ll say, for example, that the Hindu monkey god Hanuman was Adivasi.

Many nonprofits have also mushroomed in Indigenous pockets. Singh said they conduct Hindu religious events to protect the environment or uplift tribals.

“If you look at the grassroots penetration of these organizations, this is amazing, beyond imagination.”

While there may be some overlap, in Singh’s opinion, there is no doubt that Sarnaism is distinct from Hinduism. Among the key differences, she pointed out, is that Adivasis consume meat, including cow and ox meat. But in Hinduism, cows are considered sacred. “[Adivasis] don’t even have an epic … they don’t believe in written text, and Hinduism comes out of a text,” she said. Tribals also don’t have the social hierarchy of caste which is prevalent among Hindus.

In Angada, a heated debate ensued when one woman said that she is Adivasi but follows Hindu traditions. Others interjected at once — “how can you say that you are Adivasi and Hindu, that’s not possible,” Debi said.

Still, many tribal people continue to consider themselves Hindus because of years of cultural assimilation, having lived closely with India’s majority faith. But increasingly more and more are identifying as Sarna, Singh explained.

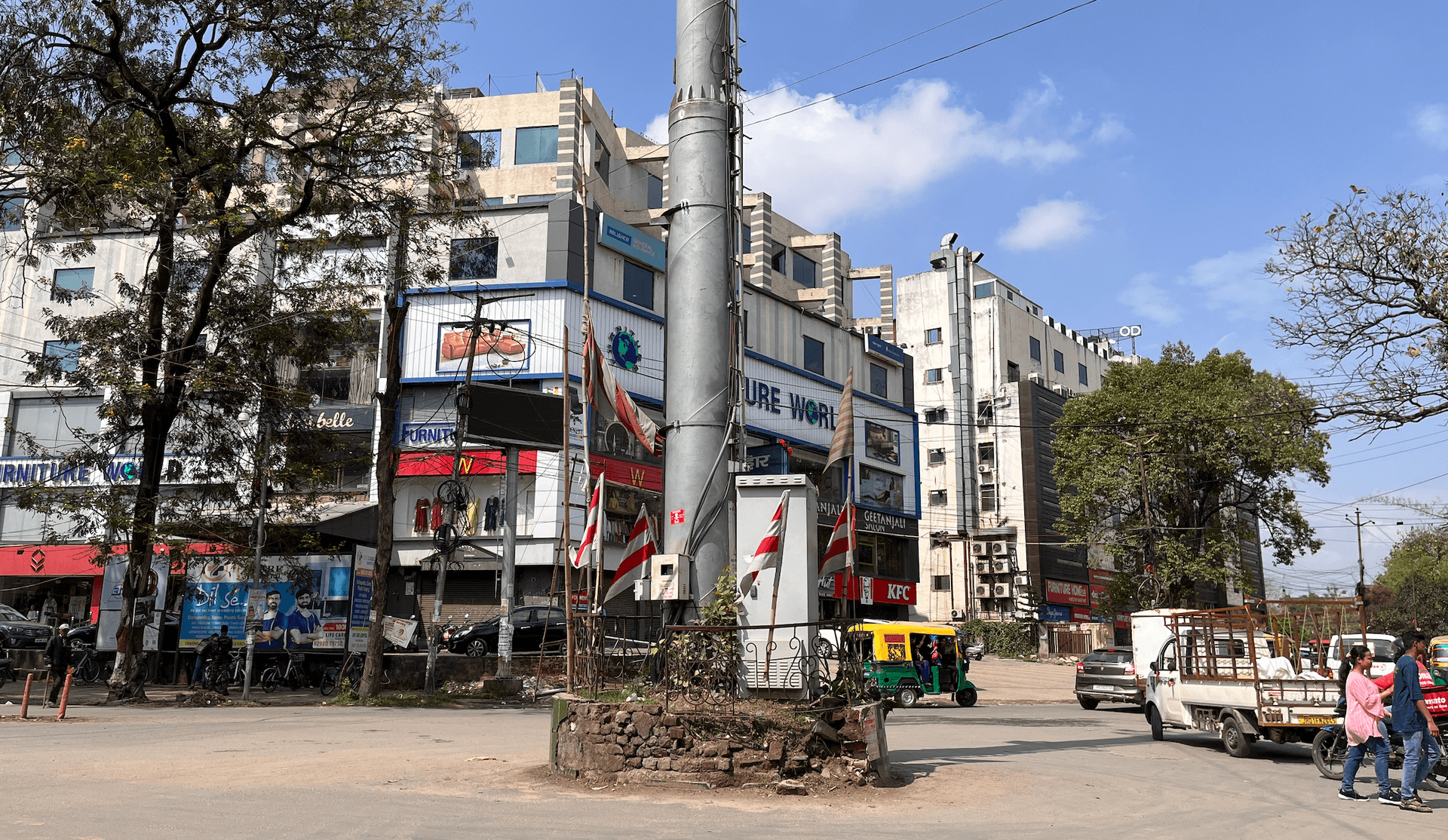

More visible red and white flags

Over the past decade or so, tribal groups have coalesced and are asserting their identity louder than ever. One indicator of the rising Adivasi pride is the striped red and white flag symbolizing tribal identity which is now ubiquitous in areas with sizable tribal populations. In Ranchi, you can spot it on people’s rooftops, on fences around sacred groves and even in traffic circles.

“Nowadays, … we are feeling very proud, and we are uniting in favor of our culture and tradition,” said Mathura Kandir, a resident of Khunti, Jharkhand, who hails from the Munda tribe.

Singh also said that the flag has “come up as a great factor of camaraderie” among tribal people.

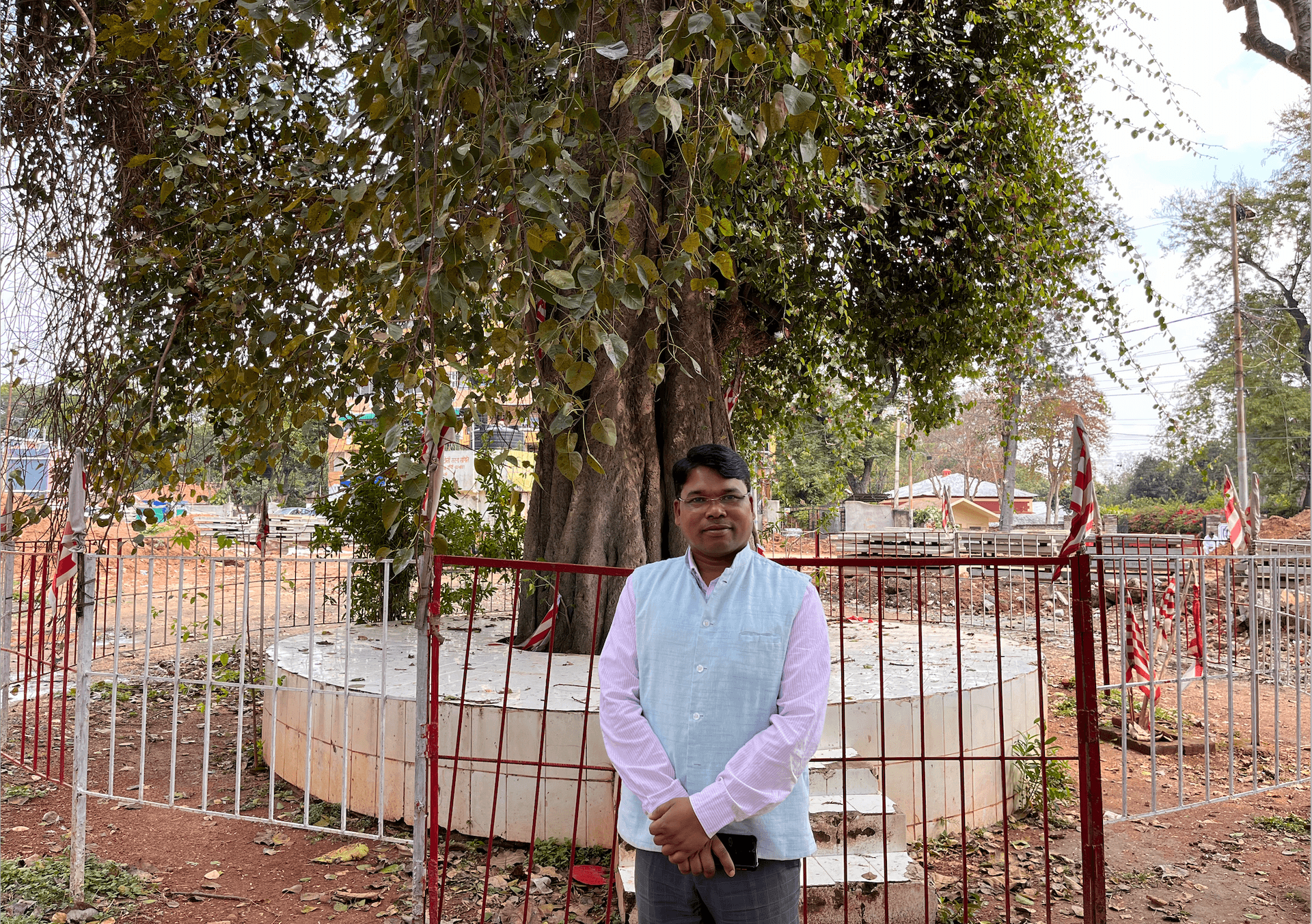

To raise awareness about Sarnaism, Adivasi Sengel Abhiyaan, an organization led by Murmu, the former member of parliament, has been organizing protests in March demanding recognition for the Sarna faith. At least two states, including Jharkhand, have passed resolutions to recognize Sarnaism in the next census—pending approval from the federal government. At a rally in Jharkhand in February, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s political rival Rahul Gandhi promised to recognize the Sarna faith if his party wins this year’s election.

But Murmu is not putting stock in Gandhi’s words. Why hasn’t Gandhi’s party, the Indian National Congress, ever raised the Sarna issue in parliament, he asked. He feels all political parties as well as tribal politicians have disappointed India’s Indigenous people. As a result, he said, Adivasis are now facing an existential threat.

“Adivasis will lose their entire identity and their culture, language, habits, thoughts and their links with nature, etc. if they will be forced to change their religion,” Murmu said. “It will be like a cultural genocide of Adivasis.”

But Murmu is confident that the Sarna faith will eventually be recognized. He insists that Sarna followers outnumber followers of other religions in India, such as the Jains, whose religion is recognized. “We don’t see any concrete reason for the central government not to grant us this religious freedom,” he said.

And if the government doesn’t budge, he said he plans on taking his fight to the Supreme Court of India.

Related: Indian govt removes parts of Muslim history from federal textbooks