The phrase “Made in Taiwan” is so much more than just a stamp on a plastic toy or a computer chip.

Now, a new cookbook is attempting to extend that label to home cooking, called “Made in Taiwan: Recipes and Stories from the Island Nation,” by Clarissa Wei with Ivy Chen.

Wei, a freelance journalist, joined The World’s Carol Hills from her home in Taipei to discuss the importance of celebrating Taiwanese identity through its cuisine and distinctive taste.

Carol Hills: The culinary side of Taiwan is really overshadowed by other cuisine from the region, especially China. How distinct is Taiwanese cooking from what we think of as Chinese cooking?

Clarissa Wei: It’s completely distinct. And I didn’t know this until I embarked on this research process. And I found that, in Taiwanese food, we have our own condiments, flavor profiles and ingredients. And by virtue of being an island, we’ve been a self-ruled democracy for many years. Our cuisine has evolved to be our own. We’re not Chinese, and we’re not anything other than Taiwanese.

I know you wrote this cookbook partly because China looms so large over Taiwan, in the way you’re referring. There is this geopolitical aspect to your writing. It’s food stories and identity, too. I mean, you grew up in California. You now live in Taiwan. Explain how important identity is to Taiwanese food.

It’s very important. Growing up in Los Angeles, I sort of conflated Taiwanese food with Chinese food. And that’s, in part, because in the ’60s and ’80s, when my parents were growing up in Taiwan, Taiwan was under martial law and put under the jurisdiction of an authoritarian government. People here were told that they were Chinese and would one day take back China. This was during the Chinese Civil War. But then Taiwan transitioned into a democracy in the ’80s and ’90s. Then, the sense of Taiwanese identity really became a thing. It became very distinct. With that came a rise in awareness of what Taiwanese food is. And so, identity plays such a huge, important part in understanding our food culture and having a distinctive Taiwanese cuisine. That wasn’t a concept 20 or 30 years ago, but it very much is the reality here in modern-day Taiwan.

I want to get back to the food now. I understand there’s a lot of influence from Japan, and this is because of the brutal handover when China turned Taiwan over to Japan in 1895. Tell us briefly about that and how it expresses itself in the food.

Yeah, that era was fascinating and a very transformative era in our culinary scene, because what the Japanese did was modernize all of our factories and industries. They were the ones who sort of built a train, a railroad track and connected Taiwan from north to south. But regarding our food, they sort of monopolized many of our key industries. So, the way that Taiwanese soy sauce, vinegar and wine, among other ingredients, are made today are still made with Japanese-era recipes. So, our soy sauce is more similar to Japanese soy sauce than Chinese soy sauce. Our black vinegar is more similar to Japanese style worcester sauce than Chinese black vinegar. And sort of again, going through these building blocks of our cuisine and finding the similarities with Japanese cuisine was kind of mindblowing to me. I kind of explained why, in America, when I was trying to make some of these recipes, but using, you know, Chinese ingredients like Shaoxing wine or light and dark soy sauce, the dish did not taste exactly the same. It was similar, but there was something off, and it was because of Japan’s influence that we have a unique pantry. But most people outside of Taiwan are unaware that with the diaspora, like my family, you’re not thinking about what you want from home when you move abroad. You’re just trying to make do with what you have and what you can get at your local supermarket.

Clarissa, you’re Taiwanese American, born in Los Angeles and grew up in California. What was your own upbringing like when it came to food and cooking?

I mean, I’m lucky I was born into a family of gluttons. My parents brought me to Taiwan every single year during winter break from the age of two to 18, and all they did was eat. We’re from the south, which is the street food capital of Taiwan. So, my relationship with Taiwanese [food] was informed at a very early age. And some of my friends here in Taiwan are surprised that I know of certain dishes that they did not know of. And it was just because my parents loved eating street food.

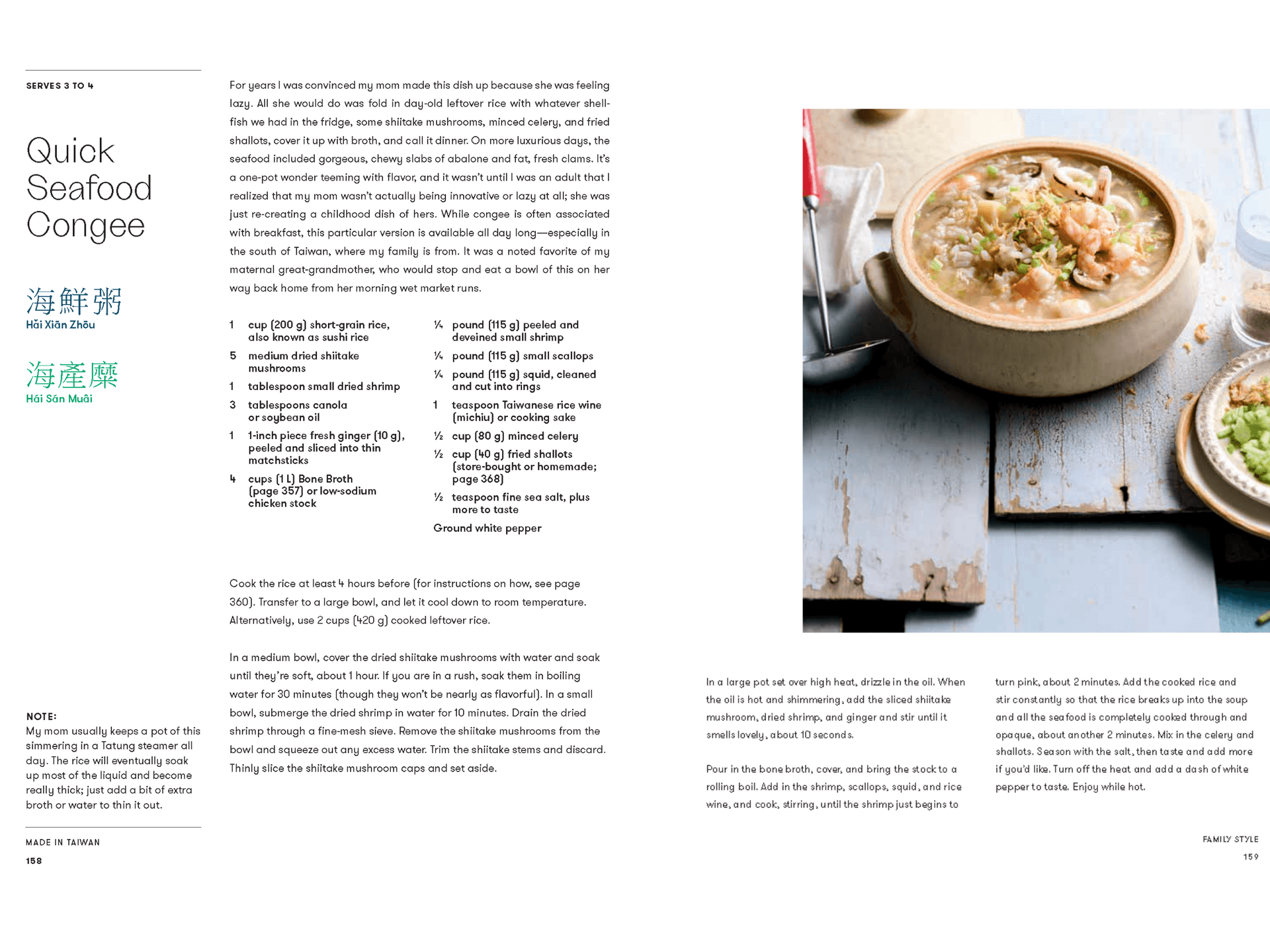

I want to turn to one of your recipes in the book. It’s called Quick Seafood Congee. This is a dish your mother makes. And I understand it’s a family favorite. Tell us about it.

This was a dish that my great-grandmother loved, as well. It’s really simple. I think most variations of congee. You have to boil rice for a long time, over an hour, and then you add sort of whatever ingredients you want at the very end. But this one is, you just take leftover rice, put it in a broth, it could be a light sodium chicken broth, and then throw in seafood. Taiwan is an island, so we have an abundance of seafood. So, it was kind of the leftover kitchen sink assortment of the day. And it comes together in 10 minutes and it serves at the peripheral of wet markets in the morning. And it’s very hearty. You can add celery inside for crunch. I love it because it’s simple, and it sort of represents how simple Taiwanese cuisine can be. I love the seafood aspect because I think many people forget that we are an island, and the ocean surrounds us with abundant seafood. So, it’s a family favorite, and anyone can make it. You just have to have leftover rice and some seafood in the refrigerator.

You mentioned in the notes in your cookbook that your mom usually keeps the quick seafood congee simmering in a Tatung steamer. That’s another thing: the dishes and the bowls in the photos. In your book, you were really seeking authenticity, weren’t you, regarding what you decided to show?

Yeah, I worked with an all-Taiwanese team, my food stylist and photographer. They felt this immense pressure to represent Taiwan as best as they could in the photography. So, when you flip through the books, every dish, every bowl, every table setting was put there on purpose, and these are bowls and ceramics that would be served in the context of that dish. So, for example, we have an oil rice recipe that’s usually served when you give birth to a boy and have a celebration with all of your friends. It’s served in that traditional basin with red etchings all around. These things are very subtle, and the average American or foreign reader would not be able to pick up on it. But I do have photography notes scattered throughout the book to guide people through this process. The idea is for these to sort of be Easter eggs. You know, it’s not just the text that will inform you about the history and the culture of Taiwan, but really the photography, as well. We didn’t want just to highlight the food. We wanted to highlight the culture and the story and give context for the food in terms of the photography.

Sign up for our daily newsletter