Ropati Opa sat in the shade on the side of the road beside a carpet of tropical greenery with a massive, fringing coral reef sitting just offshore.

He is the mayor of Leone, a seaside village on American Samoa, an island in the South Pacific between Hawaii and New Zealand. As such, it’s his responsibility to help ensure that the coral there stays healthy.

Corals attract fish that are beneficial to the Samoan ecosystem, and they buffer the island from strong waves. They also attract tourists who snorkel in the ocean to explore the reefs.

“We need to have a good coral in this ocean,” Opa said. “It’s very important. They have good fish.”

Despite prevailing narratives of coral bleaching and decline, the reefs of American Samoa have been particularly resilient to warming temperatures that have laid waste to other corals. Scientists there are finding out why, and looking for ways to use this knowledge to help reefs in other parts of the world.

Dan Barshis, a coral biologist at Old Dominion University, has worked on the American Samoan reefs for 19 years.

“It’s like a black-sand beach, almost,” Barshis said of the shoreline, where gentle waves lapped against sand the color of coffee grounds.

“We’re going to go swim out and show you what a real South Pacific reef looks like,” he said, a pile of snorkeling gear beside him.

He donned his gear, fell back into water the temperature of a warm bath, and swam out to the reef in about five minutes.

He said that there were several signs that this reef was healthy. The corals were of many different types as well as sizes, indicating varying ages. A parrotfish swam by, and then a butterflyfish.

After bobbing in the water for a bit, the current shifted as Barshis started to make his way back. It soon became tough going — he had to fight to get to shore.

“Well, that was exciting. [A lot of] people think being a marine biologist is sitting around drinking mai tais and swimming with dolphins. But it wouldn’t be an overstatement to say that we risk our lives for science,” he said once he reached land.

Barshis takes such risks, spending long, physically demanding days studying the reefs ringing American Samoa because of the unique vibrancy of the corals there.

“They’re what we call bright spots,” Barshis said, referring to reefs that are able to withstand environmental pressures. “It is starting to become more of the exception than the rule.”

Rising ocean temperatures due to global warming have led to the demise of other reefs. Ocean warming often leads to bleaching, when corals jettison the colorful algae that nourish them.

“Looks like somebody poured bleach on the coral,” Barshis explained. “And they can starve and die if they’re not able to recover.”

Globally, coral cover has been declining over the last 15 years. But the picture is different here in American Samoa. The reefs here have bleached on occasion, but it has ultimately managed to shake the worst of it off and rebound. There are other rare bright spots dotted across the world’s oceans.

“Our central question is what makes certain corals more tolerant to temperature,” Barshis said. “And what makes the strongest corals strong.”

That means looking at their genes.

“We’re sequencing their genomes to see what genes and what mutations might be causing them to be adapted for high-temperature events.”

Genome sequencing could help scientists look for those genes in corals elsewhere in the world to identify and protect similarly resilient reefs. They could rebuild beleaguered reefs by seeding them with hardier young reefs from nearby. This approach would effectively buy corals time while humanity works to lower its emissions.

Barshis and his team recently finished collecting the coral samples and running them through a homemade, portable temperature-tolerance test.

“I tell people that we can set up a whole system — basically, a whole research lab in about four or five hours,” he said.

This ability is key because there’s no official marine lab on American Samoa.

His innovation consists of several coolers, a handful of heating and cooling elements and various customized electronic controlling devices. After conducting his tests, Barshis shipped the samples back to the American mainland where the coral genomes are currently being sequenced.

This idea that the reefs here may help save reefs elsewhere is something that makes people in American Samoa proud.

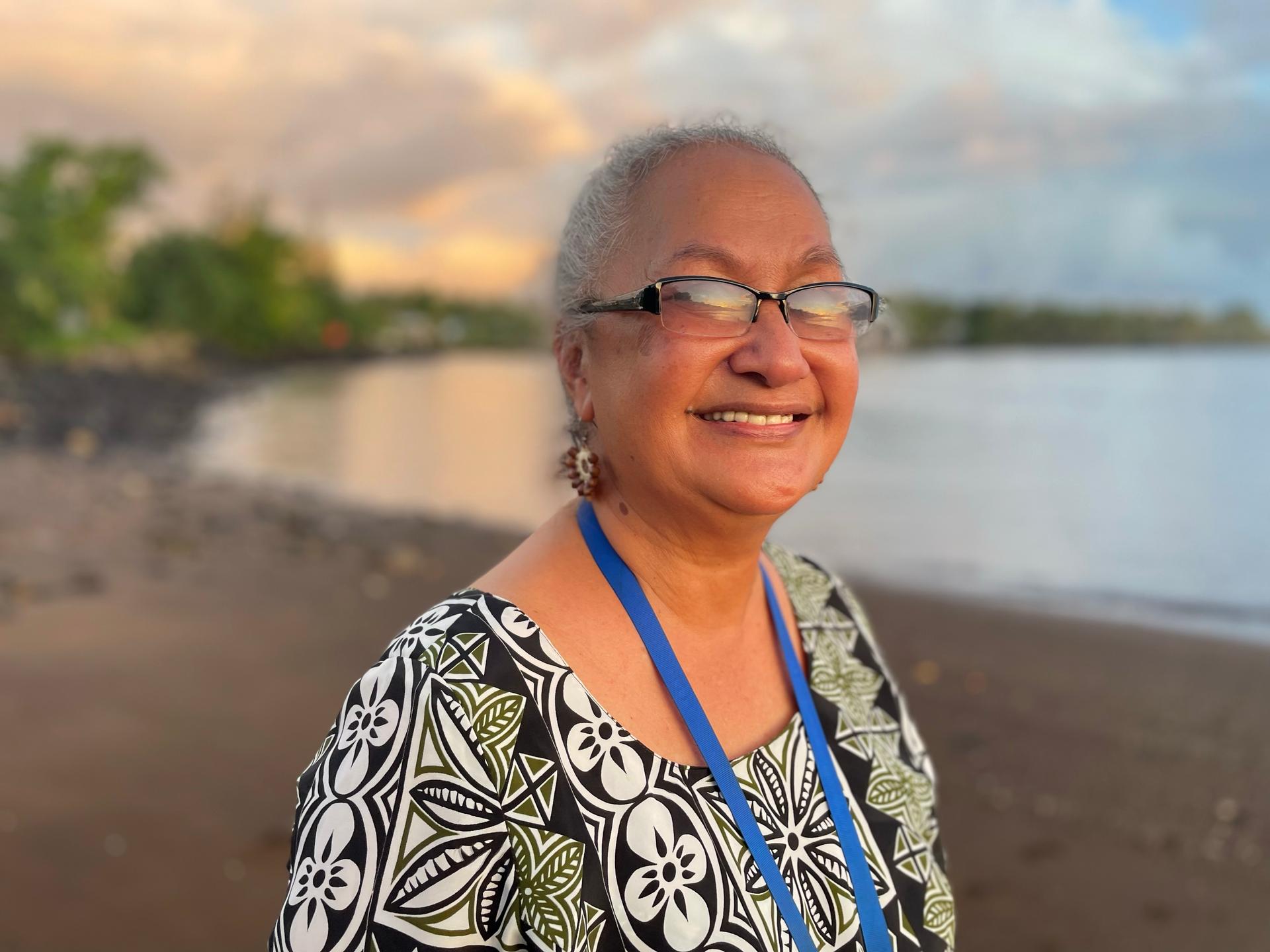

“It’s a good feeling that we have something of great value here,” said Valentine Vaeoso, the former national coral reef management fellow on the island. “That it’s possible that we have the answer that can help our brothers and sisters from other parts of the world to protect these amazing marine ecosystems.”

Sana Lynch, who coordinates the Coral Reef Advisory Group, agreed. She pointed to our deepening understanding of the relationship between genetics and resilience: “Research like Dan’s is important,” she said, “because we can use our coral diversity and hopefully expand the findings here to other places to increase coral abundance.”

Barshis’ work adds to a backdrop of coral conservation work on the island, championed by the American Samoa Department of Marine and Wildlife Resources. On top of restoration efforts, this also involves monitoring invasive algae and sponges in harbors and tracking bilgewater of incoming vessels, said Casidhe Mahuka, the invasive species coordinator for the department.

“When I look out there, I see the future that’s going to be challenging and also the future that requires champions,” said Andra Samoa, a former member of the American Samoan House of Representatives, as she eyed the watery horizon.

Some of these champions should definitely be humans, she said. But it’s the coral that may hold valuable secrets in its genes that will help keep the reef ecosystem alive.