Pape Aly Guéye — also known as “Paco Pat Ghetto” — remembers when he first heard a hip-hop song on the radio, back in the 1980s.

“Yeah, absolutely. It was ‘Sama Yaye,’ one of the first raps ever recorded in Senegal, by Mbacke Dioum [Backé Chium],” said the 47-year-old rapper.

At that time, hip-hop was starting to boom in poor and working class areas, including Guediawaye, the suburban city where Paco Pat Ghetto grew up.

“This place was just a neglected area. I witnessed a lot of violence, you know, here when I was a teen, I saw people doing a lot of violence, gangbanging, I saw people who got killed, and then I was like: ‘I want to say something.’”

He said hip-hop captivated him, because he could tell serious stories in a fun way, and everyone around him seemed to like it.

Paco Pat Ghetto and some of his friends started a hip-hop group. They called it Pat Ghetto, and they wrote about the violence and insecurity all around them.

The group later became a pioneer of a hip-hop movement in the capital, Dakar, that demanded social and political change.

“Hip-hop over here is always talking about politics, economy and social change. This is what hip-hop is all about mostly, in Senegal,” Paco said.

But this wasn’t always the case with Senegalese hip-hop.

Unlike in the US or Europe, where hip-hop emerged from poor areas, in Senegal, it was the rich who first adopted the musical genre and lifestyle.

Bamba Ndiaye, a Senegalese hip-hop researcher at Emory University, explained that hip-hop arrived in Dakar through middle- and upper-class citizens who were able to travel abroad to places like New York in the US and France.

“And they used to come back with videocassettes and audio cassettes, and had access to cable television and music channels like MTV,” he said.

“At first, in the late ’80s, early ’90s, you had, for instance, hip-hop music that tends to focus more on love, you know, ego-tripping,” he added.

One example is the group Positive Black Soul (PBS), the first Senegalese hip-hop group to get international attention.

In the early days, Senegalese artists rapped mostly in French. But when they started switching to Wolof — the most common local language in Senegal — more people started listening, and using it to tell their own tales, Ndiaye said.

“The politically engaged hip-hop started when youth from working class neighborhoods made hip-hop also a way of expressing discontent, but also criticizing the regime that was in place, the socialist regime.

That was the ruling party in Senegal since they got their independence from France in the 1960s, until the year 2000. During this period, several hip-hop artists got censored, arrested and even beaten up for speaking out against authorities.

But that didn’t prevent Senegalese rappers from engaging in political critique.

Back in 2011, there was an anti-government movement called the Y’en a Marre, or “I’m Fed Up,” that was led by rappers and journalists to encourage young people to vote.

It was during that time when rappers Xuman and Keyti came up with the idea of rapping the news.

For several years, every week, they would take hard news, put it to a beat and mix it with a little bit of humor.

Xuman would rap the news in Wolof, and Keyti would do it in French, to imitate the way news is delivered in TV newscasts in Senegal.

“We wanted to bridge the gap between young people and the news, because, many times, they miss what’s really happening in the country,” Xuman said. “And sometimes the government is signing new laws to change people’s lives. And people don’t even know that, you know, their life is about to change.”

His journal Rappé was so successful that it was copied in other countries abroad.

“For me, that’s an achievement, because back in the day, we used to copy American hip-hop, the American concept and, you know, it happened that now people are copying our concept,” he said.

Xuman is not rapping the weekly news anymore, but he’s still engaged in politics. In early June, when protests erupted in Dakar, he launched a new single about police brutality and democracy.

Many rappers in Senegal are still asking questions about justice, equity and Africa’s place in the world.

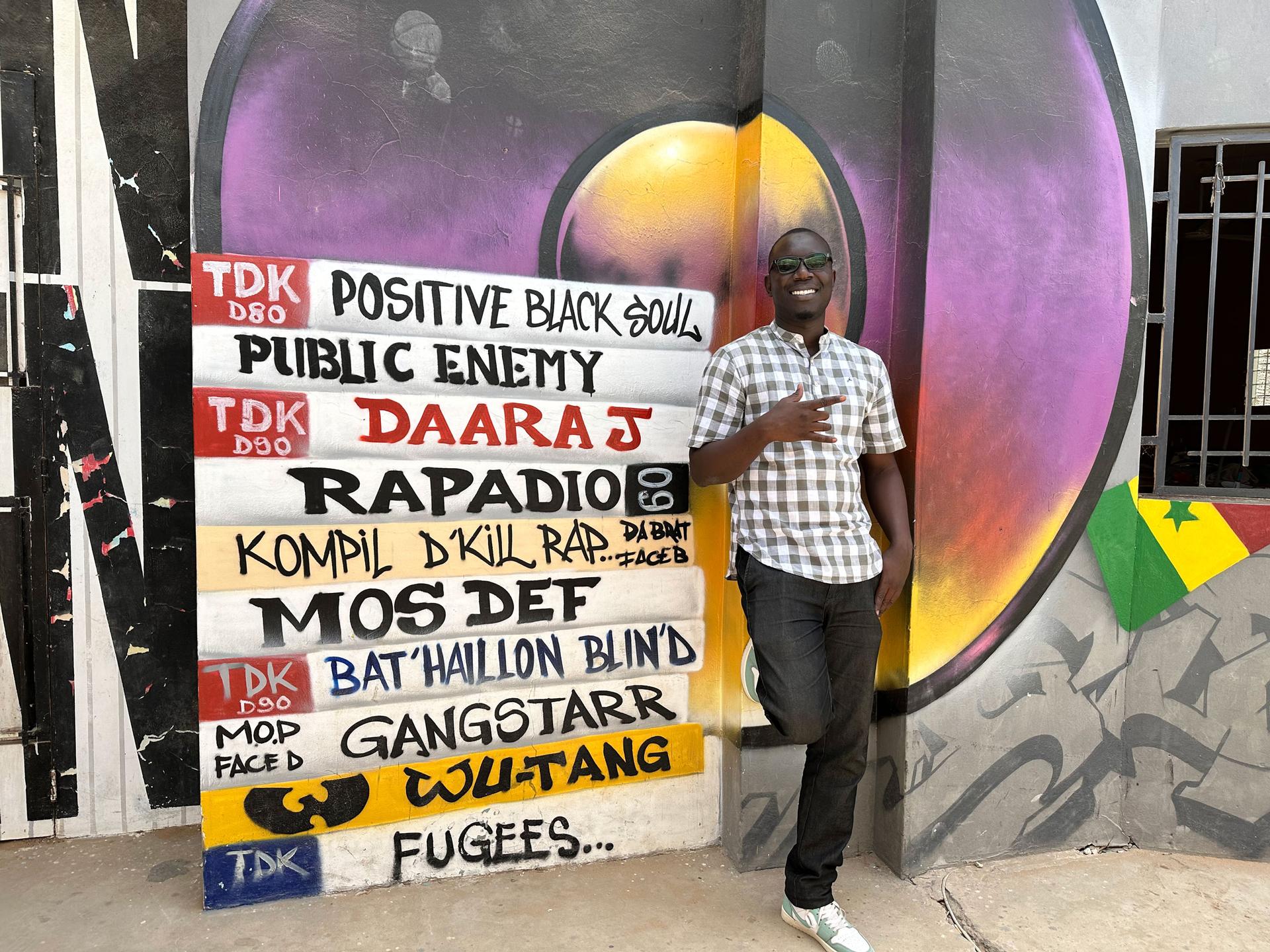

At G-Hip Hop, a youth development center in Dakar founded by Paco Pat Ghetto, students learn about songwriting, rapping, break dancing, sound engineering and music business.

But they also take courses on civic engagement. “We teach about democracy, accountability, freedom of expression and good governance,” Paco Pat Ghetto said.

The walls of G-Hop Hop are emblazoned with paintings of African activists, such as Thomas Sankara, Nelson Mandela and Winnie Mandela.

“These people were fighting for freedom and liberties, and we think we can do it too, on a local scale,” Paco Pat Ghetto said.

At his center, he hopes to inspire another generation of young Senegalese, like 21-year-old Rash Ga Guru, who was graduating from the program.

“Hip-hop saved me from the drug dealers,” he said. “I grew up around my big brothers who were dealing drugs, but hip-hop saved me from all that. It gave me the courage to be who I wanted to be.”

Editor’s note: Bamba Ndiaye contributed to this story.