When Iryna Kazakova rolled her suitcase down the gravel road last month into Hallingelille, an ecovillage located about 6 miles outside of Ringsted, Denmark, she was greeted with warm hugs.

Kazakova had just returned to Denmark after a two-month stay back home in the northeastern city of Kharkiv, in Ukraine, where she was visiting her parents. Kazakova had fled the city, located just 20 miles from the border with Russia, last summer after it had become a major target of attacks.

“I decided that I want to go to Ukraine to understand if I can [be] able to live there for a long time … to visit my friends, my family, and to understand if I’m strong enough to live with all these alarms and explosions,” she said.

But upon her return to Hallingelille, Kazakova was reminded of the work still ahead as one of the founders and coordinators of the Green Road, an initiative to connect Ukrainian refugees with safe places to stay in ecovillages across Ukraine and throughout Europe.

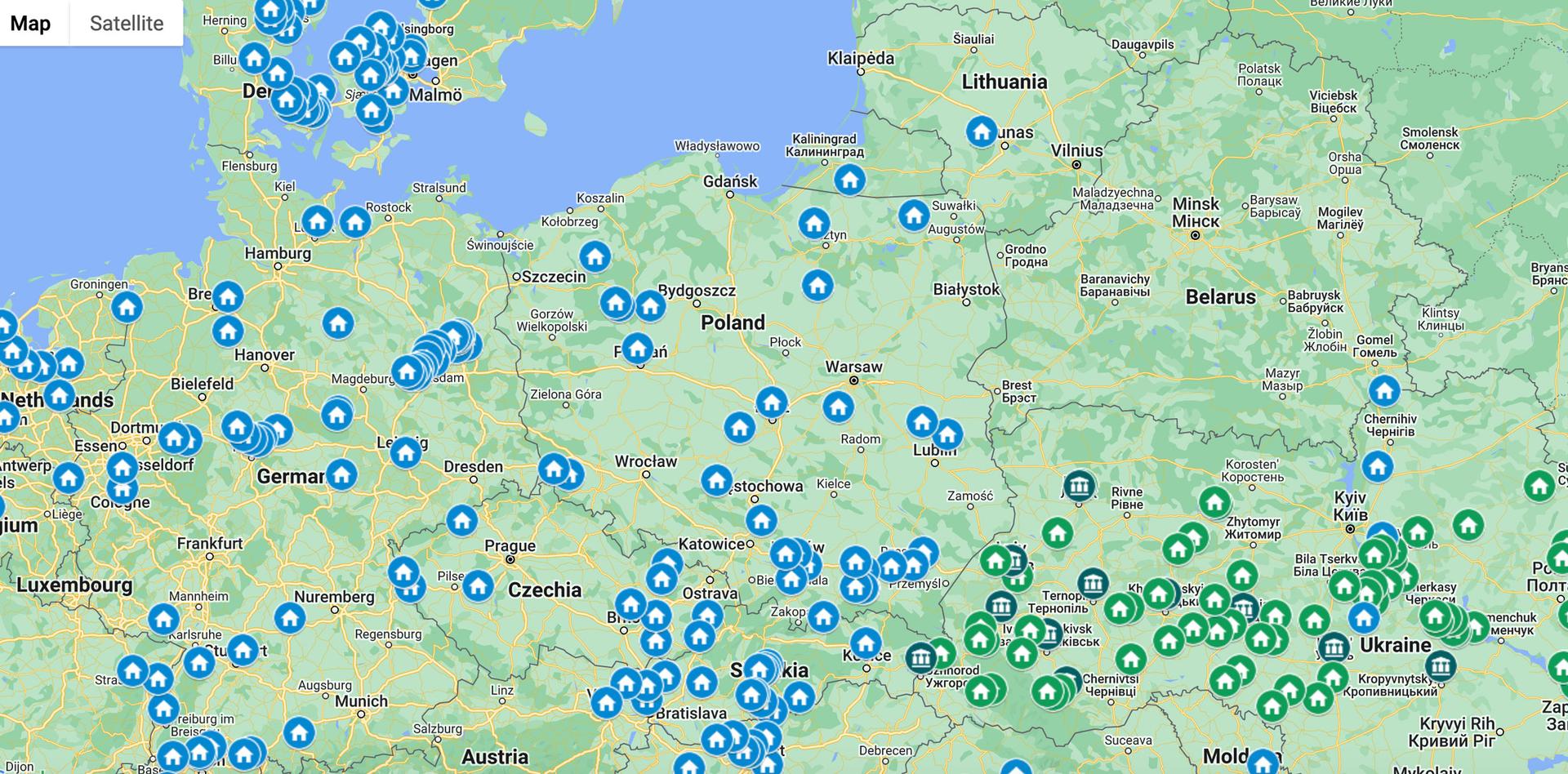

Over the last year, the Green Road project has helped relocate at least 3,000 displaced Ukrainians in 40 ecovillages throughout Ukraine and over 300 ecovillages in Europe, including Denmark. As the war continues in Ukraine, the Green Road has become a testament to the power of international friendships, networks and informal support in times of crisis.

Ecovillages are intentional communities formed by people with a common interest in sustainable living. According to the umbrella organization Global Ecovillage Network, there are over 10,000 ecovillages around the world — and no two are alike.

The ecovillage movement is said to have originated in Denmark, with roots in the Danish co-housing movement of the late 1960s. Its 49 ecovillages are some of the most established in the world and often emphasize a communal lifestyle.

Hallingelille, one of Denmark’s newer ecovillages established in 2005, is among the many European sites on the Green Road map.

This idyllic, rural community, surrounded by endless grassy fields dotted with white dandelion flowers, is home to about 50 adults and 20 children who live in 20 ecologically designed houses on land shared with several horses, sheep, pigs and a few loud roosters.

A common house overlooking a peaceful lake is the heart of this community — members share communal dinners here at least twice a week.

Over the last 15 years, residents have also built a sauna, a multipurpose warehouse, yoga and meditation center and an art studio. The group also works together to tend a forest, greenhouse and several vegetable gardens.

Far from the bombs and explosions of an ongoing war in Ukraine, it’s here where Kazakova works alongside other Ukrainian and Danish volunteers on ensuring that the Green Road project continues.

Developing the Green Road vision

Kazakova said that a flurry of phone calls with her colleague, Anastasiya Volkova, founder of Permaculture in Ukraine, and Maksym Zalevskyi, president of Global Ecovillage Network (GEN) Ukraine, led to the idea that ecovillages could provide temporary shelter for Ukrainian refugees.

Within the first few days of the invasion, calls poured in from members of Europe’s Global Ecovillage Network ready to assist — from Germany to Denmark, Hungary to Poland — and these weekly calls became a lifeline, she said.

“It was an island of stability in an unstable world for us,” she said.

A map that would become known as the Green Road began to circulate online along with a Google sheet and volunteer contact information for every ecovillage willing to host within Ukraine and across Europe, including Hallingelille.

“During the first year of war — especially the first six months — we were quite busy, like we didn’t know what would happen, so we had to prepare as much as we could. And that’s also why we applied for all these funds,” said Camilla Nielsen-Englyst, the head of Denmark’s National Association of Ecovillages (LOS), who also lives at Hallingelille.

Denmark’s Civil Society and Development organization granted about $90,000 to the Green Road project through an emergency fund — and honored them with an Initiative Prize in April. Several other individual and private donors and organizations have also raised funds and materials for the project.

Nielsen-Englyst said that established working relationships with Ukrainians on prior permaculture and ecovillage design trainings, seminars and summits over the last six years made it possible to act quickly — and collectively — on a humanitarian response.

There are currently five Ukrainian adults and five children who have followed the Green Road to Hallingelille.

Nataliya Masol and Andriy Parashchenko, originally from Kyiv, were familiar with ecovillages and heard about the Green Road online. Using the map, they sought out shelter with their five children, with brief stays in Romania, the Czech Republic, Austria and Germany before arriving in Hallingelile.

For Masol, expanding the greenhouse and planting tomatoes was the first thing she did when she arrived.

“When we came from Ukraine, it was like, we have no job and we were searching for the job and it was like, the first thing I begin to do because I need to do something. And last year, we had a lot of tomatoes growing,” she said from the sund-renched greenhouse adjacent to the common house where a new batch of tomatoes grow.

Olesia Panchenko, also from Kyiv, had stayed in Denmark before and decided to follow in Kazakova’s footsteps to Hallingelile as a volunteer with the Green Road.

Panchenko said it was a chance meeting with Kazakova at a permaculture design training in Ukraine a few years back that changed her life and set her firmly on an ecological path.

Panchenko entered the country as a tourist and only planned to stay for two months or so. But last year, Denmark passed a law called the Special Act that allows Ukrainians to bypass the asylum system and expedites residency status for a period of two years.

To receive the estimated $800 monthly stipend from the state, registered Ukrainians must take Danish-language classes and actively seek employment.

For Panchenko, that means juggling between volunteer work with the Green Road project, language classes, an unpaid internship, and ecovillage responsibilities like planting trees and tending to the vegetable gardens, though she noted how the Danes don’t necessarily take advantage of the vegetables, opting for the supermarket instead.

“Usually, you have two types of villages. I think in Ukraine, it’s a little bit different from Denmark, because in Ukraine, usually, it means that you live and learn to grow your own food. Mostly, you can be self-sufficient. And so, it’s mostly about the eco-way, not [the] community way,” Panchenko said.

Andriy Parashchenko, who came to Hallingelille with his family, said he enjoys the community focus here. He landed a job nine months ago as an IT programmer and now makes a three-hour commute back and forth to Copenhagen two days a week, working remotely the rest of the time. He said he’s earning enough to rent a house on Hallingelille where they plan to stay for now.

“In Danish culture, I like [it] a lot and I’m learning a lot — how they can be relaxed in their life and be happy and relaxed and do the same work. And how to say — they can achieve the same goals as if working hard. So, I’m learning to work in the Danish way here — relax and enjoy life,” Parashchenko said.

Support for Ukraine’s ecovillages

Whereas Danish ecovillages have a strong emphasis on community, Ukrainian ecovillages have traditionally focused moreso on self-sufficiency.

Before the war, Kazakova said about 600 people were living in simple, modest ecovillages scattered across Ukraine, and that number doubled when about 600 internally displaced people arrived hoping to survive the harsh winter.

Most of the country’s 40 ecovillages had some food supplies, simple infrastructure and a way to grow food, but not much in the way of accommodations or other critical supplies.

“In the very beginning, we really needed just very simple things because people arrived in the ecovillages without anything. So, we bought food, clothes, some medicines and very, very simple things because there was nothing,” Kazakova said.

But what the villagers had — they were willing to share, she added.

Within the first six months, Green Road coordinators oversaw the delivery into Ukraine of 35 greenhouses, 10 two-wheel tractors, gardening tools, tanks for harvesting rainwater, food dehydrators and equipment for milking animals. They also sent several refrigerators, washing machines, beds and mattresses as well as building materials.

Zalevskyi, who started GEN Ukraine in 2018 with the aim to unite and strengthen the country’s existing eco-settlements, said that many people who fled to rural areas during the war came from Soviet-era industrial cities with no prior experience or interest in an ecovillage lifestyle.

This has ushered in a “new wave of evolution for our ecovillages,” Zalevskyi said, adding that community-building and conflict resolution has been necessary to mediate the clashing of ideologies — pro-Ukrainian, pro-Russian, and pro-Soviet.

“Our Green Road [connects] all of them and we [connect] because we help refugees … we have no ideological conflict because war is for helping people in collapse. It [made] us a strong network because everyone wants to help,” Zalevskyi said.

Over the last year, about 300 people eventually moved on to other living situations while 300 have stayed on in the ecovillages. The Green Road project is working with these groups to restore abandoned houses and learn new skills like nonviolent communication, decision-making, and permaculture methods that emphasize care for people and the land and fair sharing.

“We want to save [our] communities and continue community-building and we [are] using tools and instruments … to do that in harmony with people and mediate conflicts in all communities,” Zalevskyi said.

The project has now shifted to a new stage geared more toward advocacy, capacity-building and networking.

With plenty of bicycles to go around in Denmark, the group launched a bicycle project that they hope will generate income for displaced Ukrainians living in the ecovillages. They plan to collect used bicycles from Denmark to donate to about six ecovillages, and offer workshops on how to repair and build bicycles for resale.

Nielsen-Englyst, with LOS, noted that there have been challenges along the way. Hallingelille residents have had to adjust to new dynamics as hosts, and the relentless organizing to meet overwhelming needs has inevitably burned people out.

“There are some compromises and some costs and sometimes, also some conflicts,” she said. “And I think that’s also what we can see in Ukraine as well, that living together is not always easy.”

Kazakova said she keeps “the millions of Ukrainians who continue to live in fear” at the forefront of her mind while living in Denmark.

As the war continues in Ukraine, so does the Green Road toward a more peaceful and sustainable future.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!