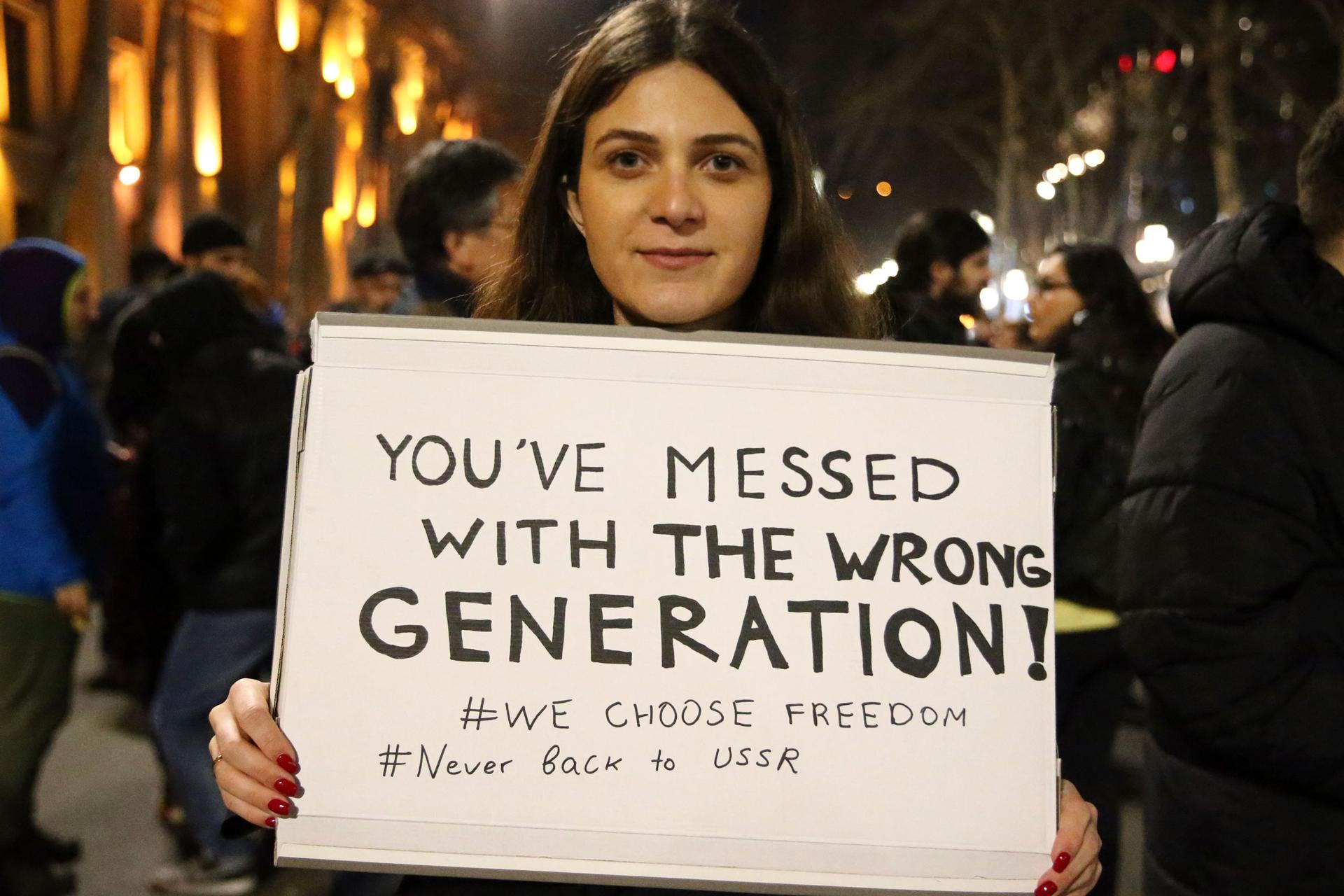

Thousands of protesters took to the streets in the Georgian capital, Tbilisi, this week to protest a proposed law that would designate organizations that receive a certain amount of funding from abroad as “foreign agents.”

Riot police used water cannons and tear gas to break up the crowds.

Critics of the legislation in Georgia argue that the law is modeled after a similar one in Russia that has made it harder for human rights organizations and independent media to operate. Lawmakers from the ruling Georgian Dream party have since announced they will not pursue passing the law, to appease the protesters, but a fierce debate about Georgia’s future continues.

Many feared this legislation would impede the country’s aspirations for membership in the European Union. And Georgian Dream, the dominant political party, has been seen as not friendly enough to the West or harsh enough with Russia.

Last summer, Ukraine and Moldova both received offers to officially become candidates for EU membership. But Georgia, which also applied for it, was given a list of tasks to complete in order to continue with the process, such as decreasing political polarization and limiting the influence of oligarchs.

The delay in advancement in the process has been a huge disappointment for Georgians, who overwhelmingly support EU membership.

“Europe represents stability and progress, that’s why we want to join the EU,” said 65-year-old Bidzina Tsurtsumia, who works at a small amusement park in Tbilisi.

Tsurtsumia said that joining the EU would mean becoming part of a more multicultural world and gaining distance from the Soviet era.

Georgia was once considered a favorite among countries seeking EU membership. But in recent years, the country’s majority Georgian Dream party has faced accusations of failing to improve the judiciary, protect the rights of LGBTQ people and of decreasing press freedoms.

“This is not the direction that a country that wants to be liberal and democratic should go,” said Sonja Schiffers, director of the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Tbsili, a think-tank associated with the German Green Party.

Georgia gets relatively good rankings from organizations like Transparency International on issues like corruption. But, Schiffers said, the problem is that, unlike Ukraine, Georgia’s government has stalled efforts to strengthen its democracy.

The ruling party’s rhetoric has detracted from aspirations to join the EU. Recently, some members of Georgian Dream have been openly hostile to American and EU officials. And other politicians formerly associated with Georgian Dream are accused of spreading anti-Western conspiracy theories.

“We have a government which argues against the West, so it’s a tragic moment,” said Giga Bokeria, leader of the opposition party European Georgia.

Bokeria hopes that Georgia will gain EU membership, because it would make the country more secure at a time when Russia is invading its neighbors.

“We need a government at this historic stage who would be banging on the doors in Washington and Brussels, explaining why both morally and pragmatically Georgia should become part of the Western security architecture,” Bokeria said.

But many leading Georgian Dream members say the party has taken significant steps to become closer to the West, at times making sacrifices like sending Georgian troops to Afghanistan to collaborate with the US and NATO.

“Unfortunately, the West has demonstrated hesitancy in coming closer to Georgia, rather than the other way around,” said Giorgi Khelashvili, a Georgian Dream politician and the deputy chair of the foreign relations committee.

Georgian Dream has also come under fire for not taking a harsh enough stance on Moscow since Russia invaded Ukraine. But politicians like Khelashvili say those criticisms are unfair.

“When you have a nuclear superpower next to you, which is threatening and menacing you incessantly, how can we risk the livelihood and lives of our population just by challenging Russia?” Khelashvili said.

But some Georgians believe that not taking a strong position against Russia’s actions in Ukraine could become a national security issue. Russia currently has defacto control of roughly 20% of Georgia’s territory.

“The problem is that Georgia cannot sit in two chairs at the same time,” said Korneli Kakachia, think-tank director of the Georgian Institute of Politics, referring to the government’s position of trying to appease both the West and Russia.

But Georgian Dream’s political messaging doesn’t turn off all Georgians.

“We’re not opposed to Russia, we just want to have relations with a peaceful Russia that’s more like nations elsewhere in Europe,” Tsurtsumia said back at the amusement park.

There, a European Union flag flutters behind Georgia’s flag — a common sight in Tbilisi, as a symbol of Georgians’ European identity and membership in the Council of Europe, a human rights organization.

The EU flag is so ubiquitous that one could easily assume the country is already part of the EU.

Georgia is still under consideration to become an EU member. But unless the government firmly embraces the West, Georgia’s path to the EU will be much more complicated.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?