The shadow of the United Fruit Company still reaches across the globe today

The Guatemalan city of Tiquisate is an industrial town of about 30,000 people not far from the Pacific coast. A big car-choked highway runs through the middle where stores and vendors hawk street food, fruit and vegetables, and just about anything else.

Just beside the highway, near the center of town, is a La Torre supermarket and a mall. Underside them, parallel with the highway, are where the rails used to run, which would take bananas from the Pacific lowlands to the ports in the Caribbean, nearly 300 miles away.

The final destination was largely US kitchens.

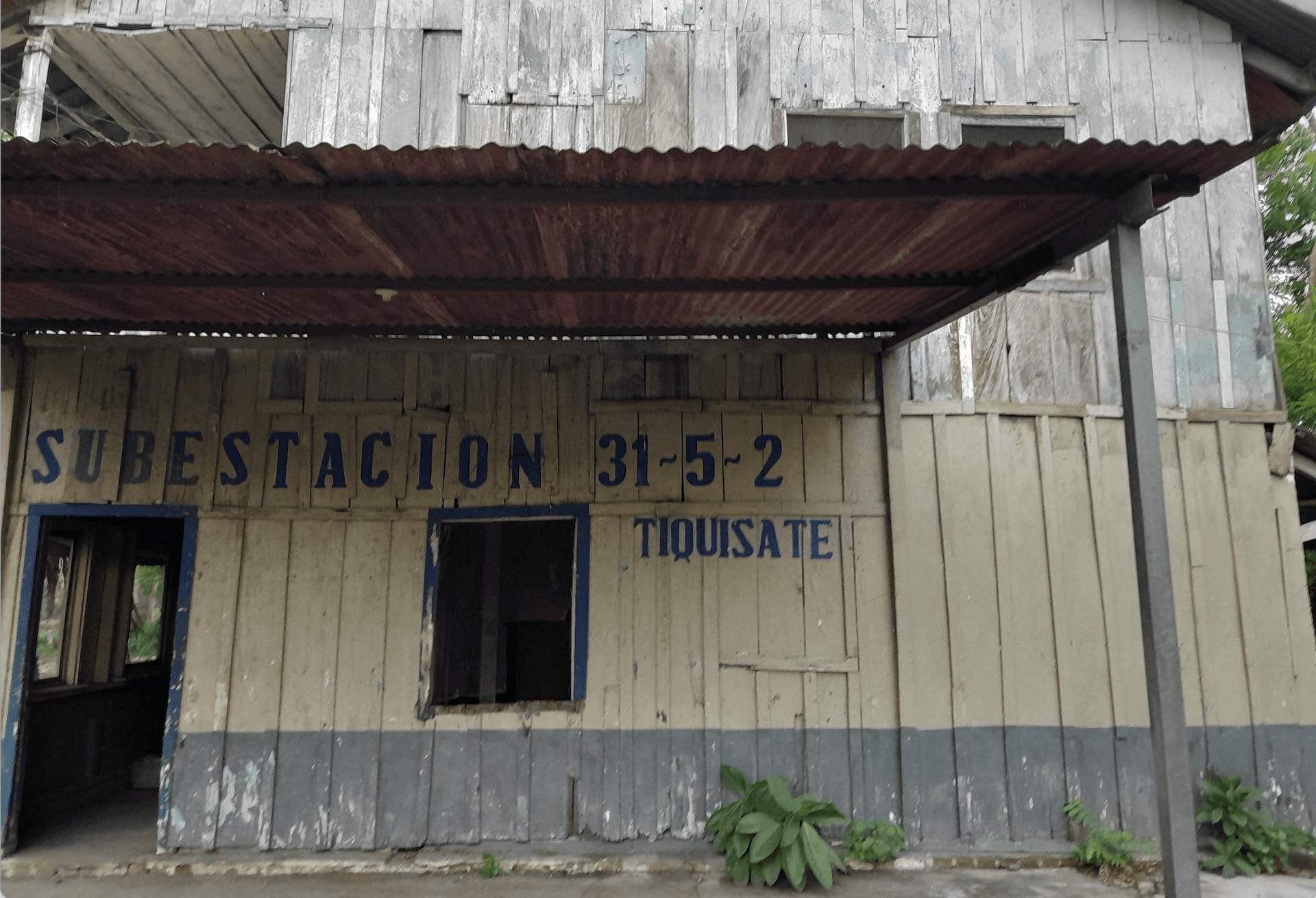

In the mid-1930s, the town of Tiquisate became the center of production for the United Fruit Company in Guatemala. Today, relics of the company can still be found hidden in plain sight throughout the city.

Founded in 1899 in Boston, United Fruit quickly grew to be the dominant force in the region. In addition to the banana plantations and railway, it also ran the post office and the telegram service. By the 1930s, with a dictator in power, United Fruit had amassed hundreds of thousands of acres of Guatemalan land. It was the country’s single largest landowner. Its reach was so ubiquitous that people called the company El Pulpo — the octopus.

“[United Fruit] was far more powerful than the Guatemalan state.”

“United Fruit had developed an overwhelming presence in Guatemala. In fact, it was far more powerful than the Guatemalan state. It had resources far beyond anything that the local Guatemalans could come up with,” said Stephen Kinzer, a former New York Times correspondent who co-authored the book, “Bitter Fruit,” about the United Fruit and the CIA-backed coup in Guatemala.

Remnants of United Fruit

Several neighborhoods were built to house United Fruit employees in Tiquisate at the time. Today, those buildings can still be found mixed into the landscape: green, two-story wooden homes with tin gable roofs. Rows of houses stretch on for blocks.

“Yeah, there are many of these little houses that are still around,” said Carla Juarez, who is a receptionist at a white two-story hotel there. “They called them airplane style because of the slanted roofs.”

Just beside the parking lot, one of these old United Fruit homes is falling apart. The home looks like it’s been transplanted there from the United States. As one observer later put it, the “Yankee flavor” replaced the Guatemalan in Tiquisate.

“My grandmother worked there,” Juarez said. “She was a nurse at the company hospital, so she received one just like this.”

Juarez and her mother still live in the home.

A few blocks away, lawyer Antonio Granillo and his wife sat at the bottom of the stairs that lead up to their former company home. They’ve been there for almost a decade.

“50 years ago, all of the homes were made like this,” Granillo said. “And they all were the same color: green.”

As he described it, the town was booming back then. And for many, those were the good old days. The company paid much higher wages than the average in Guatemala at the time. It provided housing. Workers poured in from the Caribbean coast and other parts of the country.

But, according to historians, it was not easy work. It involved long, backbreaking hours, no rights, dangerous quantities of pesticides and irregular pay. United Fruit ran its operations like a kingdom, and it had a huge sway over the countries in the region.

It’s where the term Banana Republic originated from.

In 1954, the company played a key role in the overthrow of Guatemala’s democratically elected president, Jacobo Árbenz, after he passed land reform that impacted United Fruit properties.

Cheap fruit

Driving around Central America today, Tiquisate is not the only place where you can glimpse into the past of United Fruit. While the company’s former homes, roads and distribution plants are mixed into the landscape, some of them are still operational. Owned by other agribusiness firms, many of them produce palm oil today.

There’s another legacy of United Fruit that is much closer to home: cheap fruit.

Even today, bananas are still $0.19 each at Trader Joe’s. That’s less than 60 cents a pound for tropical fruit in the winter in the United States and well under half the cost of a pound of local apples.

“That is the terrible legacy today of the United Fruit Company,” said Jennie Coleman, the president of Equifruit, a fair-trade banana company based in Montreal.” Often people will say, ‘Oh, banana production has changed since the bad old days.’ There have been changes. There have been improvements on pesticide use or worker safety. But the main legacy of United Fruit is promising cheap fruit.”

And experts say they’ve achieved this by transforming the banana into an industrial product.

“The banana we eat in the United States and the banana everyone eats who doesn’t live in a banana-growing country is as industrialized as a McDonald’s hamburger,” said Dan Koeppel, the author of “Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World.”

“A banana plantation is a factory,” he said. “It is a factory that produces a uniform product — as uniform as the Henry Ford-produced model. And that’s really the way to look at it. And it’s been that way for over one hundred years.”

Koeppel said tissue-cultured plants on banana farms are grown in test tubes to ensure uniformity. They require tremendous amounts of pesticides throughout their life cycles to ward off nearly a dozen common banana blights. Koeppel said that companies have kept costs low with cheap land and cheap labor.

“It’s not just because of climate that bananas are produced mostly in third-world countries,” Koeppel explained. “You don’t see a lot of export bananas coming from Australia, for example, even though they have a big internal banana crop, because it costs too much money to produce bananas. So, for over a hundred years the business model of the banana industry has been to make this the cheapest fruit in the supermarket.”

Chiquita did not respond to questions about production on their farms.

At a supermarket in El Salvador, bananas sold there from neighboring Guatemala are 34 cents a pound. That’s roughly half the cost in the US, but they only had to cross the border to get there.

In other words, United Fruit’s legacies run deep and can be found in neighborhoods in Guatemala, processing plants across Central America, and the promise of a cheap banana every time you visit your local supermarket.

This story comes to us from Michael Fox’s podcast “Under the Shadow,” about US involvement in Central America.