When war broke out between Azerbaijan and Armenia in fall 2020 over the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh, Margarita Karamyan spent 10 days hiding with her relatives in a basement in Hadrut.

For Karamyan, the incessant buzzing sound of drones used by Azerbaijan remain a vivid memory of the war.

“The sound is psychological torture because you just wait wondering if you’ll get killed or not,” she said.

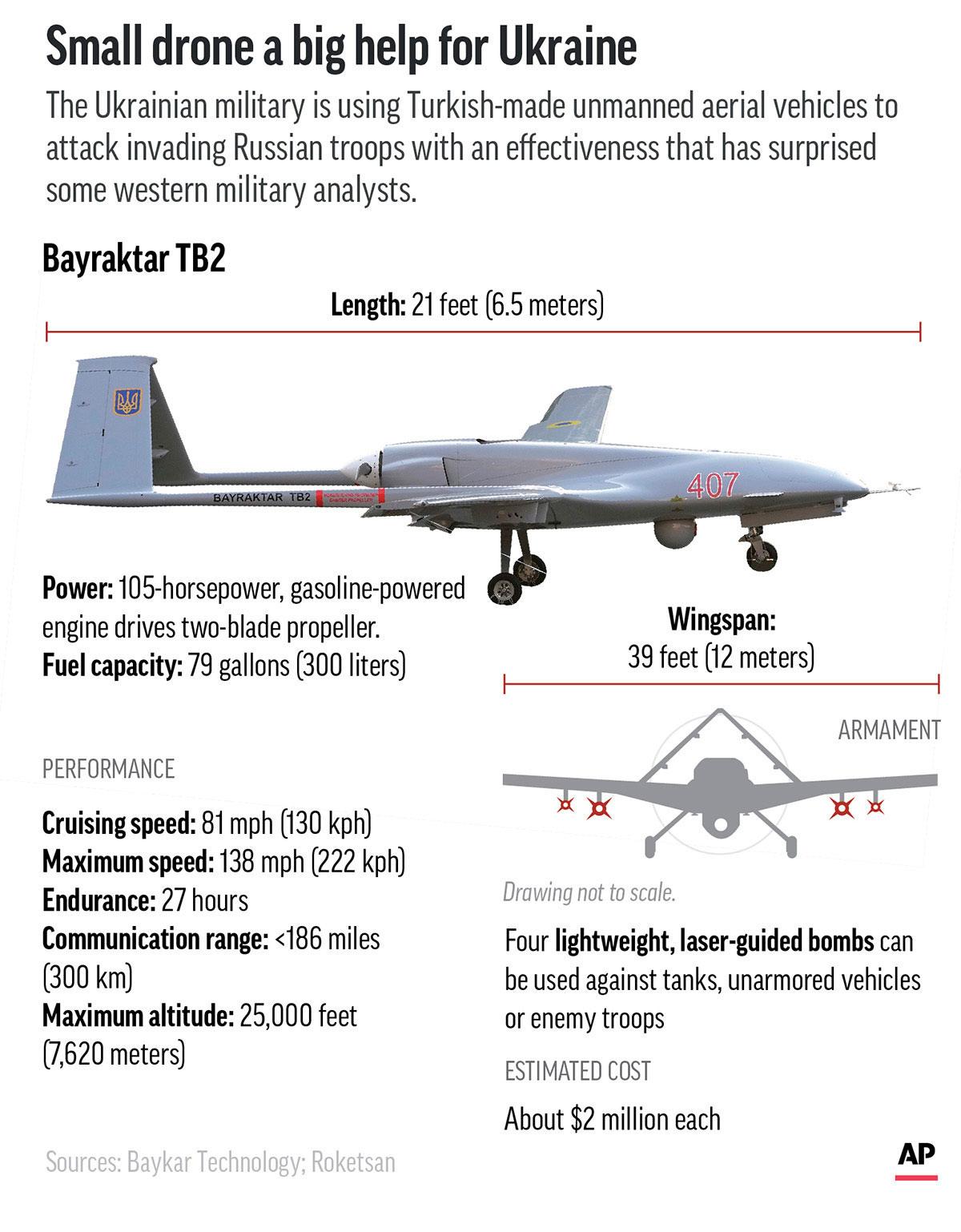

During the war, Azerbaijan succeeded in knocking out Armenia’s defenses with the aid of a Turkish drone called the Bayraktar TB2 and took over large parts of the contested territory. The 44-day war ended in a ceasefire brokered by Russia. But some say another round of war is inevitable.

Towns like Hadrut were damaged in the fighting and remain under Azerbaijan’s control. The war displaced tens of thousands of Armenians, including Karamyan, who now lives in the Armenian capital, Yerevan.

The Bayraktar drone looks like a small airplane that can strike targets with bombs. It’s also relatively cheap, making it appealing to lesser developed countries who use it in conflicts.

Ukraine used Bayraktars to help stop Russian forces from reaching Kyiv last year. The drone is so revered in Ukraine now there’s even a song about it.

After the 2020 war in Nagorno-Karabakh, trucks carrying Bayraktars rolled through Azerbaijan’s capital, Baku, in a military parade celebrating Baku’s victory.

The Bayraktar has often served as a source of pride, but for some Armenians, the drone is a symbol of alleged war crimes committed by Azerbaijan.

“These drones were used not only against the military, but also to bomb and destroy civilian communities [in Armenia],” said Arman Tatoyan, Armenia’s former human rights defender, a government role.

A Turkish company manufactures the Bayraktar; its widespread use in conflicts has helped secure Turkey’s status as a growing weapons supplier.

The drone has also become part of Turkish foreign policy. Turkey is a close ally with Azerbaijan and directly aided Baku to operate the drones used against Armenia in the 2020 war, according to Tatoyan.

Proving whether Bayraktars are responsible for carrying out war crimes against Armenians, like killing civilians, has proven extremely difficult.

Anahit Harutyunyan, the operations manager with the Center for Truth and Justice, a law clinic in Armenia that investigates potential war crimes committed by Azerbaijan, said it’s rare to find debris in warzones like serial numbers that clearly identifies drones for launching attacks.

“It’s a really huge tragedy that you can’t gather facts to show how our people were killed during the war because after the explosion, there’s nothing left, Harutyunyan said.

But not everyone is convinced the Bayraktar is such an important part of warfare.

Shant Abraamyan, an Armenian who grew up in the US and fought in the 2020 war in Nagorno-Karabakh himself, said he frequently saw drones flying overhead during the war. But he said that the soldiers in his group were scattered enough in the mountains that drones would not hit them.

“People like to say, ‘Oh, Bayraktar is like this big bad wolf,’ but they’re not some magical thing that’s going to win you the war,” Abraamyan said.

Abraamyan said the Armenian government didn’t come down hard enough on Azerbaijan with the weapons they had.

Leonid Nersisyan, a military analyst and research fellow at the Applied Policy Research Institute of Armenia, said that drones did play a key role in Azerbaijan’s victory, but he thinks they have received too much credit for determining the war’s outcome.

Nersisyan said that Armenia’s army was poorly organized during the war while Azerbaijan, on the other hand, benefited greatly from Turkey, which provided Baku’s military with training derived from NATO protocols.

The Bayraktar may be even more effective off the battlefield.

“Drones provide high-quality videos, and they are helpful for informational warfare,” Nersisyan said.

Videos of strikes operated by Azerbaijan’s drones were some of the main footage of the 2020 war that first appeared on the internet. Nersisyan said the media sometimes overuses drone videos, which can overstate the role that the Bayraktar has in conflicts in both Armenia and Ukraine.

But Nersisyan said Turkish drones are still a major threat because Armenia never replenished their air defense systems after the last war. Armenia gets most of their arms from Russia, which is overextended in Ukraine.

“Russia practically stopped all its arms exports not only to Armenia, but also everywhere else,” Nersisyan said.

Armenia is now trying to receive arms supplies from India, but vulnerabilities in Armenia’s ability to defend itself from drones remain as tensions with Azerbaijan continue to escalate.

Last fall, Azerbaijan attacked border regions in Armenia that killed more than 100 Armenian soldiers.

And for more than three months, Azerbaijani environmental activists suspected of taking orders from Baku have blocked the only road connecting Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, known as the Lachin corridor, which has deprived ethnic Armenians living in the region from receiving vital food and medical supplies.

Russia has peacekeepers in Nagorno-Karabakh who are tasked with providing security in the Lachin corridor, but so far, they have failed to stop the blockade.

Former US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Yerevan last year in a show of support to the country, but the United States has yet to offer any tangible aid to Armenia that could help resolve tensions with Azerbaijan.

“The West only really helps us with words by telling Azerbaijan not to attack Armenia, but that doesn’t stop them,” said Vaghinak Vartanov, who helps run a school in Yerevan called VOMA that trains Armenian civilians in basic combat techniques as well as first aid and mountaineering skills.

Many Armenians now believe that a future, full-scale war with Azerbaijan is inevitable.

On a recent Saturday night in an old movie theater in Yerevan where VOMA runs trainings, an instructor dressed in army fatigues directed a group of men and women aiming fake kalashnikovs at a Soviet-era mosaic on the wall.

In a future conflict, the students would use these skills to protect their country from a potential invasion by Azerbaijan, similar to how Ukrainian civilians have defended their country.

“We’re ready for peace,” Vartanov said as the students train, “but the only way to bring peace is to prepare for war.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!