An unusual announcement appeared in Russian Dark Web forums in June 2020. Amid the hundreds of ads offering stolen credit card numbers and batches of personally identifiable information, there was a call for papers.

“We’re kicking off the summer Paper Contest,” it read. “Accepted article topics include any methods for procuring shells, malware and malware coding, viruses, trojans, bot development … monetization.”

Jon DiMaggio, chief security analyst at Analyst1, remembers seeing the ad when it first appeared and thinking to himself how odd it was to have some sort of academic call for papers pop up where cybercriminals tend to gather.

“They’re calling for papers, like, in the name of education of the criminal community,” DiMaggio told the “Click Here” podcast. “As if they were helping out the young guys and gals coming up,” in the cybercrime world.

DiMaggio said that the summer paper contest was a strangely highbrow way to appeal to the vanity of a group that typically doesn’t get to claim much public credit for what they do: cybercriminals.

That may partially explain why the contest ended up generating a huge amount of interest. The $5,000 cash prize for the best paper probably had something to do with it, too. But it wasn’t just the novelty of introducing a contest that made DiMaggio take notice — it was who was sponsoring the competition: a Russian ransomware gang called LockBit.

That contest was the first in a long list of initiatives, unrelated to the bread-and-butter running of a ransomware gang, that a hacker named LockBitSupp did over the past two years to professionalize the group, according to DiMaggio, who spent more than a year inside LockBit private channels interacting with LockBitSupp and other members.

“LockBitSupp considers himself to be like a CEO of a company,” said DiMaggio, who believes LockBitSupp is more than just a support person or administrator for the group as his moniker implies.

This is just one of the insights from a new report called “Ransomware Diaries: Volume 1,” released on Jan. 16, in which DiMaggio revealed how he infiltrated the group and what he learned while on the inside. “Click Here” was given an early look at it.

DiMaggio watched as LockBitSupp began upgrading the group’s infrastructure. He saw him recruit developers who were creating LockBit’s easy-to-use ransomware dashboards. He was privy to the group’s efforts to upend the traditional ransomware payment model by putting affiliates in charge.

LockBitSupp’s focus on professionalizing the group is part of the reason why LockBit has found such success in the cybercriminal world — the group accounted for 44% of the total ransomware attacks launched last year.

“He’s running it as a business and it’s why I believe that he spends so much time on criminal forums interacting and talking and being accessible,” DiMaggio said.

“He wants LockBit to be popular and easy to approach.”

Last year, the cybercriminal world was rocked by a researcher who released years of internal chat logs from the Russian ransomware group Conti. The chat logs came to be known as the “Panama Papers” of the ransomware world, because they gave observers an unfiltered look at how ransomware operations work.

DiMaggio’s report was a version of that. By sharing some of the chats he started and was privy to, he laid out how LockBit came to eclipse other ransomware operations — and what it plans to do in the future.

Do you speak German?

DiMaggio’s relationship with LockBit and its leader started with a failed job interview. It was 2020, and LockBit was looking for coders. They put up a job posting for affiliates and DiMaggio applied. He didn’t expect to get very far in the process. “I’m not a hacker,” he said.

Even so, he did get a virtual interview and got as far as the LockBit assessment test. It was meant to measure whether an applicant really had the coding chops they claimed to have or were just “script kiddies” exaggerating abilities.

“The assessment test they gave me showed I wasn’t qualified enough,” DiMaggio said. “I didn’t expect to get through, but they did let me remain in their TOX channel,” which, it turns out, was a goldmine.

TOX is a peer-to-peer instant messaging service, a kind of encrypted Skype that many cybercriminals prefer. Much of the world’s ransomware negotiations happen on TOX. So, being in the TOX channel for LockBit allowed DiMaggio to be a kind of fly on the wall, watching cybercriminals at work and in the wild.

But DiMaggio wanted to be more than a fly on the wall — he wanted to engage. So, he baited LockBitSupp. “I asked him if he thought an account being used by another ransomware group had been compromised by the FBI,” DiMaggio said.

“I didn’t care what he said, but I saw it as an opportunity, because he seemed so paranoid about that taking place.”

DiMaggio was pretending to be one of LockBit’s affiliates, or subcontractors, and he told LockBitSupp that the affiliates could be in jeopardy, too.

“And he was like, you know, I prefer to have these conversations not on these forums, but on our own infrastructure,” and he asked DiMaggio (or at least who he was pretending to be) to move the conversation there. The only problem was, LockBit was a Russian ransomware gang, and DiMaggio didn’t speak Russian.

“So, I started off the conversation with German, and of course then he says, ‘I don’t speak German,'” DiMaggio said. “But here’s the thing. All of them speak a little bit of English, because English speakers are their primary victims.”

So, DiMaggio would often start conversations with ransomware actors with a ploy.

“I’m like, ‘do you speak English,’ type of thing. And they say, ‘yes.’ And I’ll say, ‘OK, well why don’t we try to communicate in English then?'” he said. “And then, I just have to remember to make sure my English isn’t too good as I communicate, but it works. And, and that’s exactly what I did with LockBit.”

Before he knew it, he and LockBitSupp were in the group’s private channel talking and, in some ways, LockBitSupp was exactly what DiMaggio was expecting. He was a guy who exaggerated his accomplishments and trash-talked other groups. Where he was different was in his sense that, in order for the ransomware industry to get “next level” it needed to be run more like a traditional business, and LockBitSupp had a plan to do just that.

“He constantly did things to get their name out there and then capitalize on the opportunity,” DiMaggio said.

Tattoo for $500

LockBit started with a logo. A few ransomware groups — like Vice Society — were experimenting with that. LockBit’s logo — a red, white and black retro-looking rendition of their name — started appearing on everything they touched: on their leaks website, letterhead, ransom notes, anything they sponsored.

Then they tried their hand at a little IRL branding. They began offering people $500 to $1,000 to tattoo the LockBit logo on their bodies.

“I heard that, I’m like, there is no way anyone is going to tattoo the name of a ransomware brand and their logo on their bodies,” DiMaggio said.

“And then people did. That’s just crazy to me.”

Then LockBitSupp began working more strategically. He began studying the inefficiencies and bottlenecks in the ransomware business model, DiMaggio said. He began puzzling through what stopped the average hacker from launching successful attacks — and why they weren’t using LockBit.

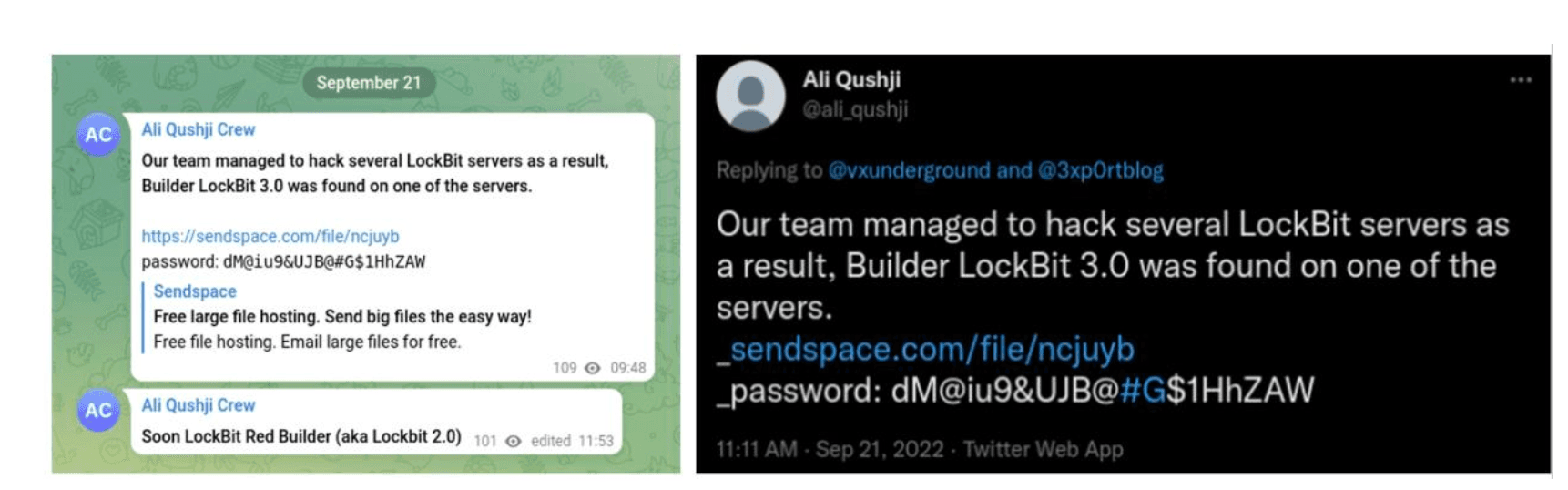

LockBitSupp’s solution was something he called LockBit Red, publicly branded as LockBit 2.0. Think of it as ransomware made easy. If you weren’t a great coder and wanted to make some cash launching ransomware attacks, not a problem. LockBit 2.0 was essentially point-and-click.

They created a dashboard to help hackers keep track of all the ransomware they had released into the world, and then improved the encrypter so attackers could steal data faster. They even created push notifications that would alert attackers when a victim responded to a ransom demand.

He took what used to require weeks of being on a network and manually entering commands and writing scripts, and automated it with a graphical interface for everybody. LockBitSupp certainly wasn’t the first person to try this, but he was the first to do it this well. LockBit’s central management console incorporated all the disparate elements of a ransomware attack, and put it in one place.

“They made a process that was convoluted, slow and was putting data outside of their own control, and made it fast, efficient and going into their own infrastructure to use,” DiMaggio said.

Flip the script

LockBitSupp’s game-changer was upending the ransomware payment system — one of the biggest problems in the cybercriminal world. The difficulty isn’t so much getting a victim to pay a ransom; that was comparatively easy. The issue was paying all the people who worked on the attack.

Traditionally, ransomware gangs use subcontractors or affiliates. Think of them as specialists — people who might be particularly good at searching for vulnerabilities or cracking into particular kinds of networks.

Each hacker would do the specific thing they’re good at then and collect that percentage of the ransom at the end, almost like an invoicing system. Given the business they’re in, it isn’t too surprising that a lot of the time they didn’t get the money that was owed.

“Not getting paid was a concern that was talked about a lot, and still is talked about a lot, on these criminal forums,” DiMaggio said.

So, Lockbit flipped the script, and put the affiliates in charge.

“You, as the affiliate, you do the negotiation and collect that money yourself and then you pay us our percentage,” DiMaggio said, which is how it worked. “Inherently, it gives them trust and removes that fear of getting ripped off.”

Once LockBit did that and upgraded their ransomware product, affiliates were banging down the doors to work with them. LockBit suddenly had more ransomware work than it knew what to do with, which goes a long way toward explaining why LockBit has been so formidable in the ransomware world today, and responsible for nearly half of all the ransomware attacks last year.

Hacking St. Mary’s

Last summer, Jon DiMaggio was in one of the LockBit chatrooms when members started crowing about its latest victim: a small Canadian town called St. Mary’s.

“The conversation was almost like high-fives and laughing at the victims themselves — poking fun at how easy it was to compromise,” DiMaggio said.

The hacker version of locker-room talk.

Attackers often go into these hacker forums and begin talking about what they just stole.

“They like to go through the data to find the, sort of, most embarrassing aspects of it … and share stuff,” said DiMaggio. “And it’s usually, it’s very much like an online bully — picking on the victim, talking trash as though it’s some big joke.”

But it doesn’t feel like some big joke on the other end.

“You feel like the world’s gonna end,” the mayor of St. Mary’s, Al Strathdee, told “Click Here.”

“It’s like being robbed. … I felt like we were invaded and robbed and it was a smash and grab.”

Strathdee was thrice elected mayor of St. Mary’s, a town of about 7,700 in southwestern Ontario. It sits a couple hours south of Toronto and about three hours north of Detroit. Its claim to fame? Thomas Edison worked here as a boy on the rail line and its outdoor quarry is Canada’s largest outdoor swimming pool.

It was the last place one would expect Lockbit to set its sights on, though Strathdee said, these days everyone’s a target.

“One of the things I’ve learned is that it’s more common than you think,” he said. “But at the time you think, you know, first of all, your first reaction is why us? And what happened?”

Back in July 2022, the city of St. Mary’s IT department was doing some routine maintenance and discovered some irregularities.

“They immediately isolated the system and unplugged the servers,” Strathdee said, adding that “our initial thought is that they didn’t even know they hit us.”

Those push notifications that LockBit launched so ransomware attackers could track their victims may have played a role in the St. Mary’s attack.

“We’re wondering whether they have systems that went back and told them that we had discovered them in our systems, or maybe an alarm went off,” he said, adding that the final report on the breach may tell them that for sure.

There was a ransom demand and city leaders thought about paying it, though he wouldn’t say how much it was.

What Strathdee found stunning, after he did some reading about Lockbit, was that the group thought to strike his town. He was told that people could actually rent software from LockBit and take a cut, which means it could have been anyone,” he said.

In other words, it may not have been LockBit itself that hacked them, but one of those affiliate groups. Strathdee said it is pretty clear to him that just about everyone is vulnerable and everyone has to prepare for ransomware attacks now.

“You know, you talk a lot about roads and sewers, and different things like sidewalks and things, as being infrastructure,” he said.

Cybersecurity is “becoming infrastructure as well, and we have to start thinking of it more. And we need to spend more money, a lot more money than we ever expected.”

LockBit 3.0

Jon DiMaggio’s main question: Who does this kind of thing? Who thinks a hospital or a small city or school is a legitimate target?

DiMaggio used to do this kind of profiling and analysis for government intelligence agencies. After spending more than a year lurking in chat rooms, lobbing in questions and watching the interactions between LockBitSupp and others in the ransomware world, what he’s pieced together is that LockbitSupp is a white male in his mid- to late-30s living in Russia or Eastern Europe. He grew up poor, and that’s central to understanding him.

“He says that he was picked on for not having money and not having a lot of friends,” DiMaggio said. “So, because of that, this builds in these insecurities, and when you get a lot of success, that breeds a very strong ego.

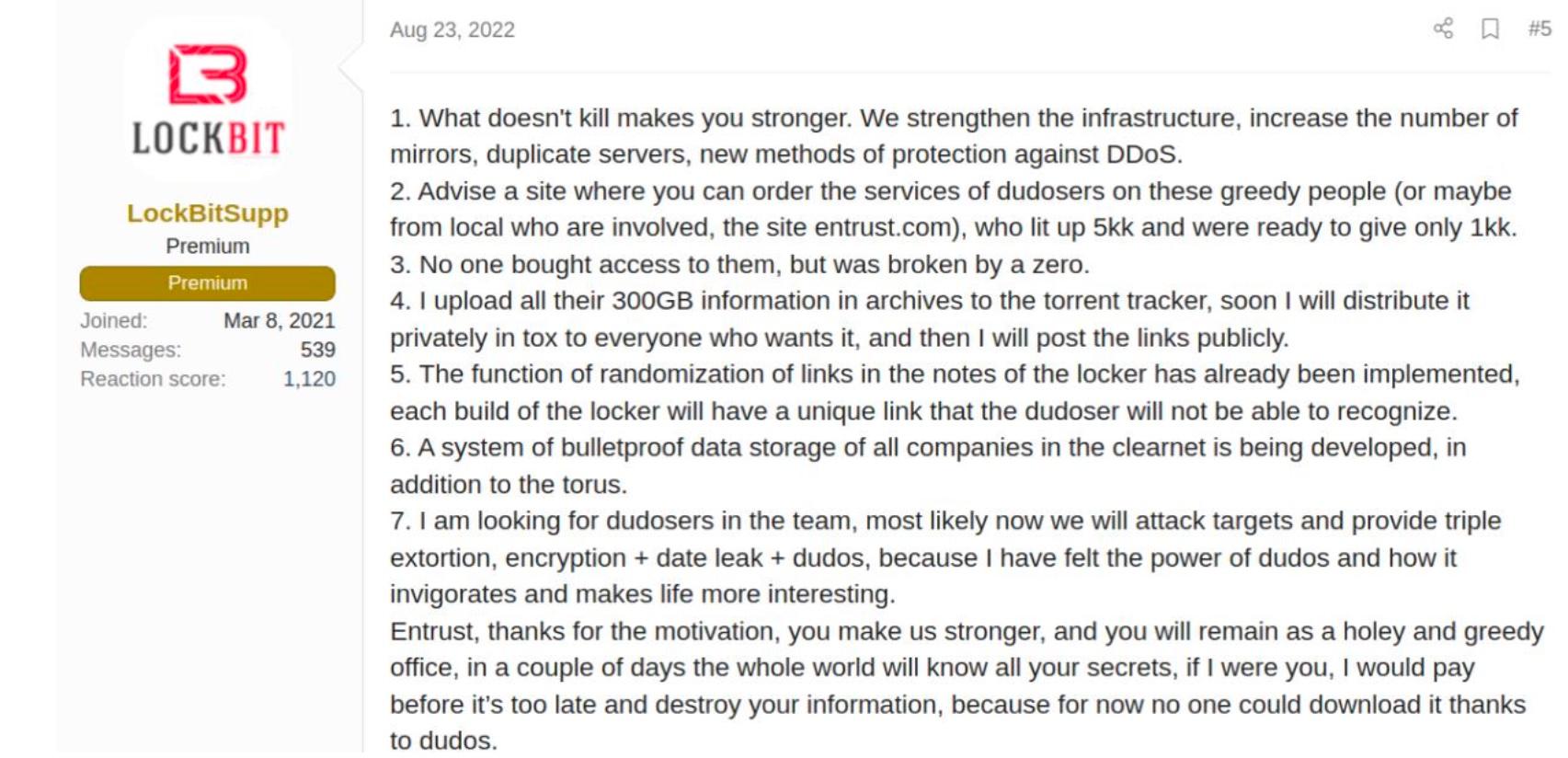

DiMaggio said LockBitSupp sees himself as a prince of darkness, like a Batman villain bent on sowing destruction. It is why he is always escalating. For example, he wants to add Denial of Service attacks to the group’s ransomware menu. Because, LockBitSupp said in one chat, “DDoS attacks invigorate” him and “make life more interesting.”

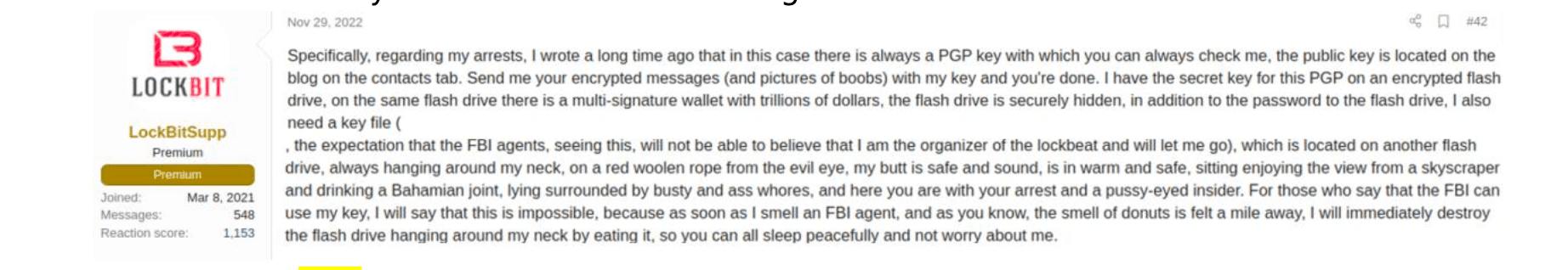

But the thing about so-called supervillains is that, down deep, they have issues. For all their bravado, they’re a little insecure. And in Lockbit’s case — maybe less surprisingly — he’s super paranoid. That paranoia let DiMaggio get closer than he probably should have, and prevented LockBitSupp, DiMaggio said, from enjoying all the money he’s making.

“He can’t travel to places. He can’t go on vacation or leave certain areas of the world,” DiMaggio said. And because of all of this, he doesn’t seem happy.

DiMaggio assumes once the report goes public, any personas he used to get close to LockBitSupp and his operation will be burned. But he maintains that the whole exercise was an important one, because security officials are so focused on the technical parts of ransomware, they forget that the people behind these attacks are only human.

Remembering that, he said, provides a roadmap on how to bring these groups down. DiMaggio said it would be easy to play on LockBitSupp’s paranoia and use information campaigns against him.

Which could explain why DiMaggio said his parting words to LockBitSupp would be this: “Watch your back. There’s researchers, there’s analysts, there’s law enforcement agencies and entire governments that are coming for you. Look over your shoulder. And when it’s hard to sleep at night,” DiMaggio paused, “That makes me smile.”

An earlier version of this story appeared on The Record. With reporting by Sean Powers and Will Jarvis.

Related: What comes after Hydra, the darknet marketplace that changed everything?

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!