‘Art is the answer to all this’: This Brazilian artist went from fighting fires to uplifting Black portraiture

Brazilian artist Dalton Paula’s home studio door is always open, but visitors must first walk through a green corridor he planted himself.

“These gardens have sacred plants,” he said. “The idea is that this is a space that welcomes, that protects.”

Growing up in Brazil as a Black man, Paula said he missed seeing people who looked like him on movies and TV. At 40, he creates paintings, photos and installations about Black communities.

His works have been acquired by major art institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and The Art Institute of Chicago.

Paula lives on the outskirts of Goiânia, the capital of Goiás state. He shares his home with his partner of 14 years, film professor Conceição de Maria Ferreira da Silva. In 2021, they turned their home into an art school called Sertão Negro, or Black Hinterland.

“This is a Quilombo, a space that is based in the Afro Brazilian universe and considers the soil and the plants sacred,” he said. Traditionally, Quilombos are settlements created during colonial times by people who’d escaped enslavement.

Sertão Negro offers a wide range of classes like pottery and capoeira, movie screenings and access to a library with more than 1,000 books.

The school also hosts an artists’ residency and sells their work. Paula is now building three bedrooms that will house future artists. They will pay for the residency and that income will help finance the school.

Sertão Negro employs nine people, including three artists who also work as assistants.

Artist and assistant Lucelia Maciel is currently working on a sculptural project. She said that Sertão Negro taught her the business side of running a studio. She enjoys working with other artists and getting Paula’s feedback, but he can be tough sometimes.

“He is demanding,” she said. “An expression that he uses a lot is: ‘Think about layers, bring more layers.’”

A chemist, a firefighter

Paula has been making art since he was a teenager, but he first went to college to study chemistry. And for 12 years, he worked full-time as a firefighter. When he began his visual arts studies at the federal University of Goiás, he worked the night shift.

“I would rescue people who had been shot, stabbed, injured in car crashes. And then I would study, like a zombie, falling asleep,” he said.

His firefighter colleagues became some of his first clients.

His inspiration for the school comes from the idea that art is a tool and that the role of the artist is to respond to the world, referring to the recent vandalism of government buildings by supporters of former President Jair Bolsonaro.

“In this moment, with the attacks, art is an answer to all of this,” he said.

As a Black man, he said he is often seen as a threat. To capture this experience, he created a photo performance, standing in front of walls with his eyes or head covered. In 2011, that work was selected for the group show “Rumos Artes Visuais,” organized by Itaú Cultural in São Paulo.

His big break came in 2016 when he was invited to present at the prestigious São Paulo Biennial.

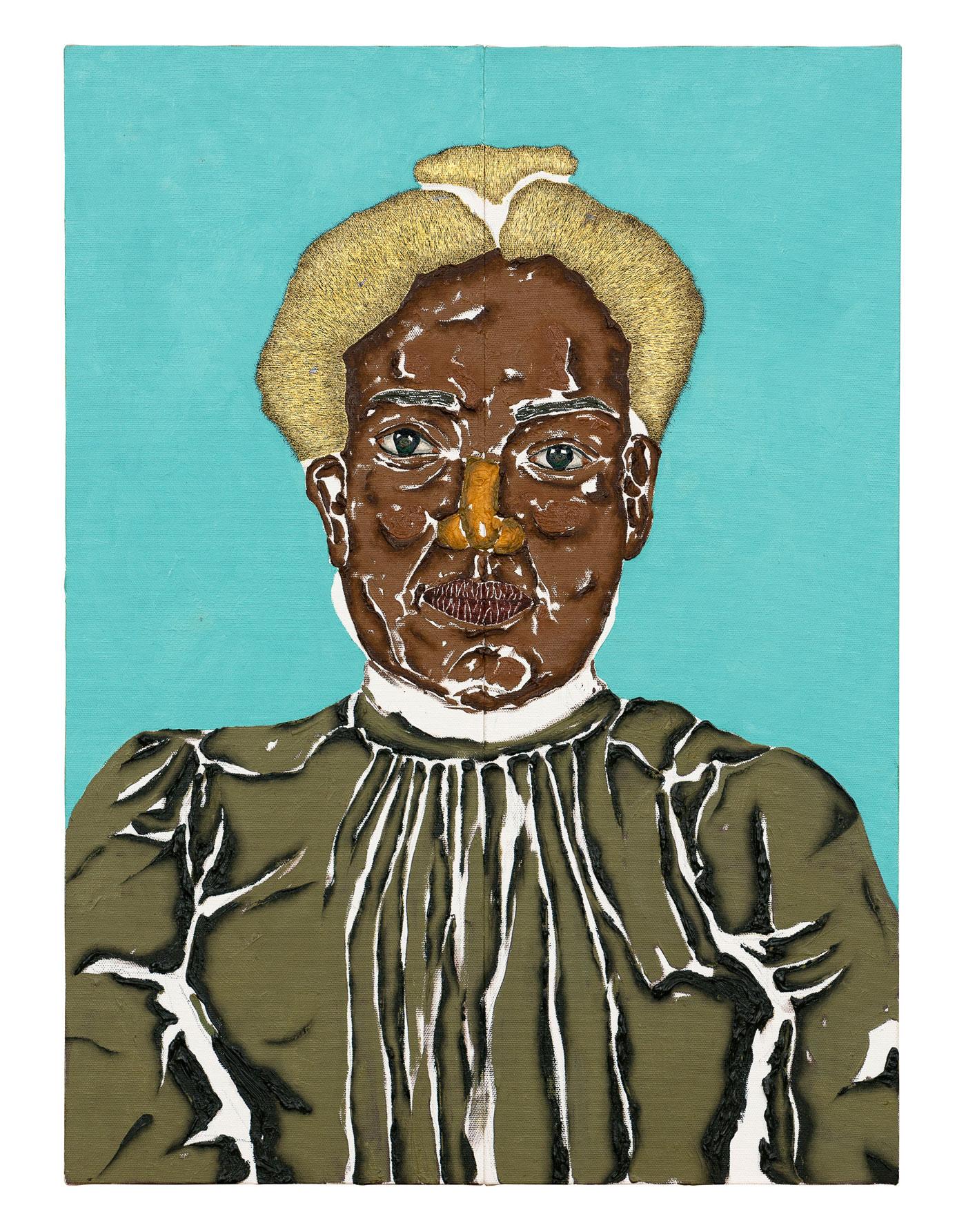

Two years later, he started visiting Quilombo communities in his state. He now photographs current residents and paints their portraits using research about those who lived in the same areas in the 18th and 19th centuries.

“He takes the history and he takes the photographs and he matches them. So, he gives these people who were never photographed, or drawn, an identity,” said Carolyn Alexander, owner of the Soho gallery Alexander and Bonin, which represents Paula in New York.

The intricate, layered portraits use gold leaf for hair. Each painting costs $25,000.

Alexander first met Paula at an art fair in Brazil in 2018 and invited him to New York for a residency in 2020. The pandemic limited Paula’s plans, but he produced a lot of art and sold six paintings to the city’s Museum of Modern Art.

“I personally knew that Dalton Paula was somebody who I wanted to be in a life-long relationship with,” said Thomas Jean Lax, a curator at MoMA specializing in Black art and performance who orchestrated the purchase.

Lax first encountered Paula’s work in early 2020, when he visited studios and museums in Brazil. He said he appreciates that, with these paintings, Paula is imagining who his subjects could have been.

“That dimension of the unknown, of embracing the unknown, is really important not only for his work, but also gives Black artists the full range of possibilities as we bear witness to the things that they have made,” he said.

Paula’s latest piece is a commission from Pinacoteca de São Paulo, a museum devoted to Brazilian art. The installation is called “Cotton Route,” featuring several bottles and jars covered in white, cotton canvas with painted images that are displayed on several draped altars.

“I found all of this kind of enigmatic,” said Caroline Paz, a graduate student in cultural criticism who visited the show in early January.

The installation speaks to the economic and cultural impact of cotton production in Brazil and the US.

Paz said the work holds important symbolism for Black people like her.

“Many are still on the margins, it’s a constant struggle. But it’s very important to know that we have here, today, the work of someone who can show his art to the world, particularly because he is a Black artist,” she said.

Paula is now working on several new projects, including a series of paintings of Black children. And he and his partner are planning on having a child.

“My partner says that I passed through the ‘dreamline’ many times, and I grabbed dreams of those who didn’t want many dreams,” Paula said, laughing.

A few of these projects use materials that Paula has never worked with before.

“I’m always doing this exercise — when something is very set — I create new challenges for myself. And that’s the work of a lifetime, the work of an artist,” he said.

The exhibition at Pinacoteca closes at the end of January.

The World is an independent newsroom. We’re not funded by billionaires; instead, we rely on readers and listeners like you. As a listener, you’re a crucial part of our team and our global community. Your support is vital to running our nonprofit newsroom, and we can’t do this work without you. Will you support The World with a gift today? Donations made between now and Dec. 31 will be matched 1:1. Thanks for investing in our work!