Cuban dissident artists behind hit protest song ‘Patria y Vida’ sentenced to prison

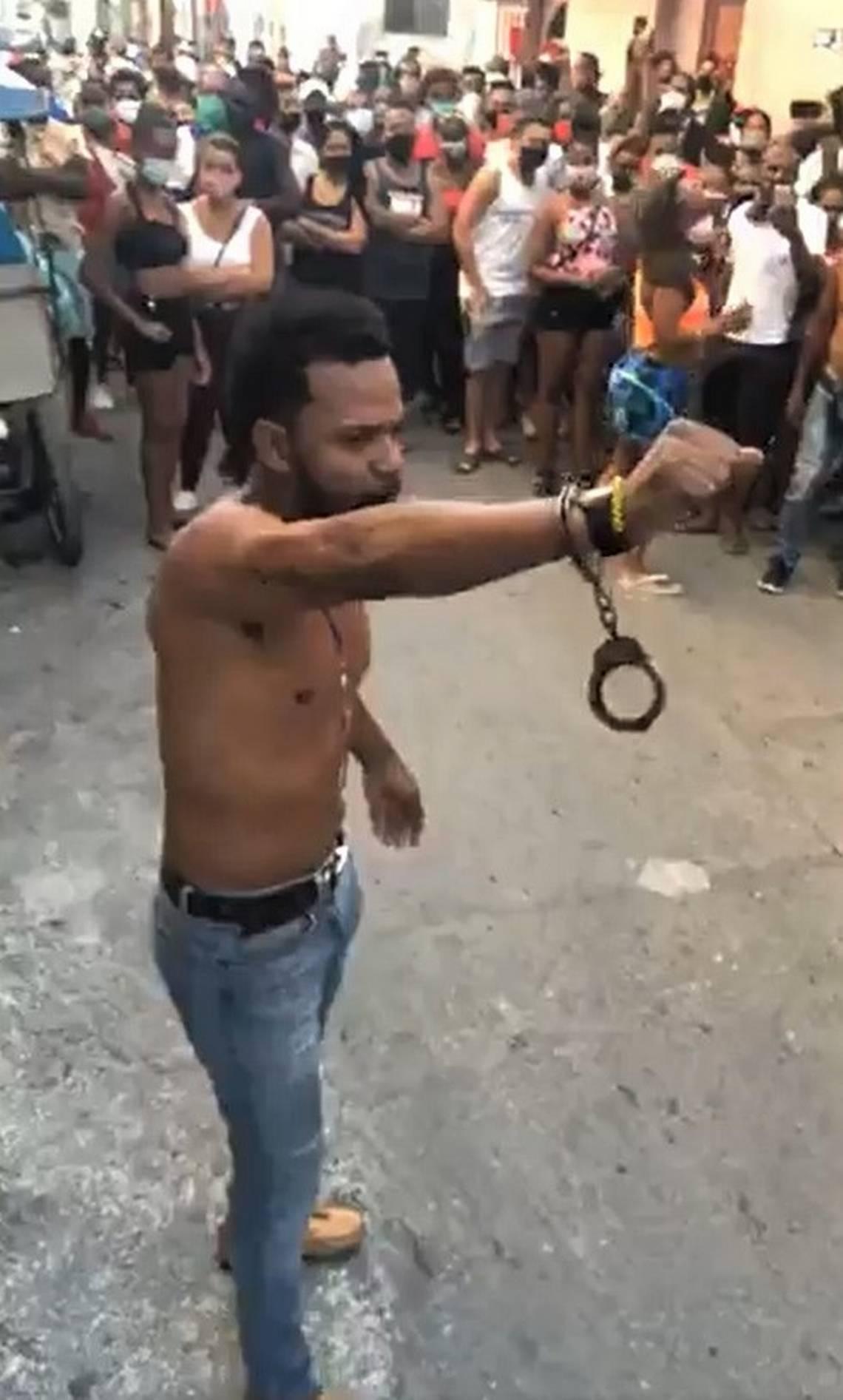

Otero Alcántara during his performance “La Bandera Es De Todos,” a piece where he wore the Cuban flag for 30 days.

Two Cuban artists who took part in composing and recording the protest hit “Patria y Vida” were sentenced to prison terms last week.

Rapper Maykel Castillo “El Osorbo” and visual artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara received nine-year and five-year terms, respectively, according to the island’s attorney general last Friday.

Castillo and Otero Alcántara are leaders of the San Isidro Movement, a group of Cuban artists who have used different artistic expressions to denounce political repression on the island.

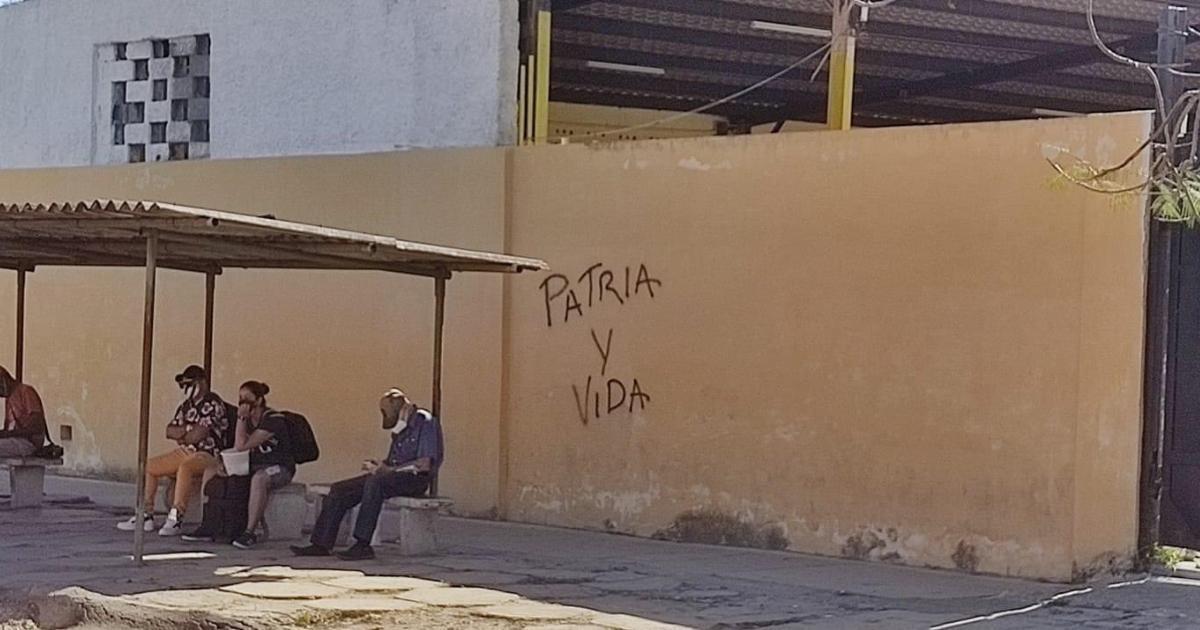

“Patria y Vida,” which means “Homeland and Life” is a play on one of the most iconic slogans of the Cuban revolution, “Patria o Muerte,” meaning “homeland or death.” It was a phrase used by revolutionary Che Guevara, and one that former Cuban President Fidel Castro often used to end his speeches.

And the new song quickly became the anthem for last July’s historic demonstrations that demanded an end to economic misery and political repression in Cuba.

Their song was released early last year by a group of Cuban artists both living in Cuba and in exile. Castillo and Romero Alcántara, along with rapper Eliécer Marquez “El Funky” were the only ones who recorded their portions of the music video in Cuba itself.

“It was difficult [to record the video from Cuba] because we were hiding the whole time. We knew if we took a wrong step, there was no video,” said Castillo in an interview with Noticias CubaNet, a Cuban news outlet, right before the video was released, in February.

Months later, thousands of people absorbed its message and were marching to the “Patria y Vida” slogan across the country.

In Cuba, criticizing the government is officially against the law. Nearly 1,500 people were arrested in relation to the protests, and half of them remain in jail, according to 11J, an organization that tracks detentions in Cuba.

The Cuban government accused the San Isidro Movement of “catalyzing the protests” and called it a cultural counterrevolution sponsored by the United States’ government.

Castillo was detained in May 2021 for participating in a protest a month earlier. He remained incarcerated until last week when he was found guilty of “contempt, public disorder, and defamation of institutions and organizations, heroes and martyrs,” according to the Cuban attorney general office.

Alcántara Otero was detained on July 11 — the very day that the protests erupted — after he posted on social media his intentions to join the demonstrations. The court argued his “express intention, sustained over time, of offending the national flag, through the publication of photos on social media where it is used in denigrating acts, accompanied by notoriously offensive and disrespectful expressions, underestimating nationalistic feelings and pride the Cuban people profess to our national flag,” the attorney general office said in the statement.

Castillo has also been prosecuted for a performance in 2019 in which he wore the Cuban flag draped over his shoulders for 30 days straight, a response to a Cuban law limiting the ways that the national flag can be displayed. In the video clip of “Patria y Vida,” Castillo appears with the Cuban flag wrapped around his back.

Meanwhile, rapper Eliécer Márquez was able to leave Cuba and spoke from Miami, where he now lives and continues his activism.

“Maykel [Castillo] and Luis [Otero Alcántara] are in prison because they have a big reach,” Márquez said. “The government is afraid of them.”

Márquez expressed sadness and frustration “because no-one can do anything for them.”

Castillo and Otero Alcántara are both being held at a high-security prison and they are not in good health, Márquez said.

Supporters of the revolution also said the song itself was sponsored by the United States government. In 2014, an investigation from The Associated Press found a US agency secretly infiltrated Cuba’s underground hip-hop movement, recruiting unwitting rappers to spark a youth movement against the government.

But Márquez denied these accusations.

“This was an independent project launched by internationally renowned musicians, we don’t need that kind of support,” he said.

“The regime has given Cubans three options if they don’t want to go along with the dictatorship: prison, death and exile,”

“The regime has given Cubans three options if they don’t want to go along with the dictatorship: prison, death and exile,” said John Suarez, executive director of Center for a Free Cuba in Washington, DC.

He said the Cuban regime was terrified by the song after it became a hit, so it banned it on the island.

“They didn’t want these messages of liberation and freedom spreading into the population,” he added.

“Patria y Vida” now has more than 11.3 million views on YouTube and won two Latin Grammy awards last November.

Susan Thomas, a musicologist who studies Cuban music and its relation to culture and politics, said this song is a rare instance when Cuban artists directly attack the regime.

“Cuba has a long and rich history of music inspired by politics, but for the most part, critical voices have been using allusion, metaphors and allegory as the common ways of getting into the critique,” Thomas said.

The lyrics in “Patria y Vida” accuse the Cuban regime of ruining the quality of life on the island.

“No more lies, our people are asking for freedom/No more doctrines/We don’t say homeland or death anymore, but homeland and life/We are not afraid anymore. … It’s time to build what we dream of, what they destroyed with their hands.”

According to Thomas, the song features an interesting combination of factors that helped it become a hit.

“It’s very catchy, it’s openly critical, it’s mass-mediated and it pairs artists who have had international careers. It is a dangerous combination if you don’t want certain messages spreading into the population.”

Groups, including Amnesty International, Human Rights Foundation and Freedom House have denounced the lack of a fair trial for Castillo and Otero Alcántara, and are calling for their immediate release.

Related: ‘Homeland and life’: The chant to Cuba’s anti-government protests

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?