A new documentary uncovers the story behind China’s racist ‘blessings video’ trend

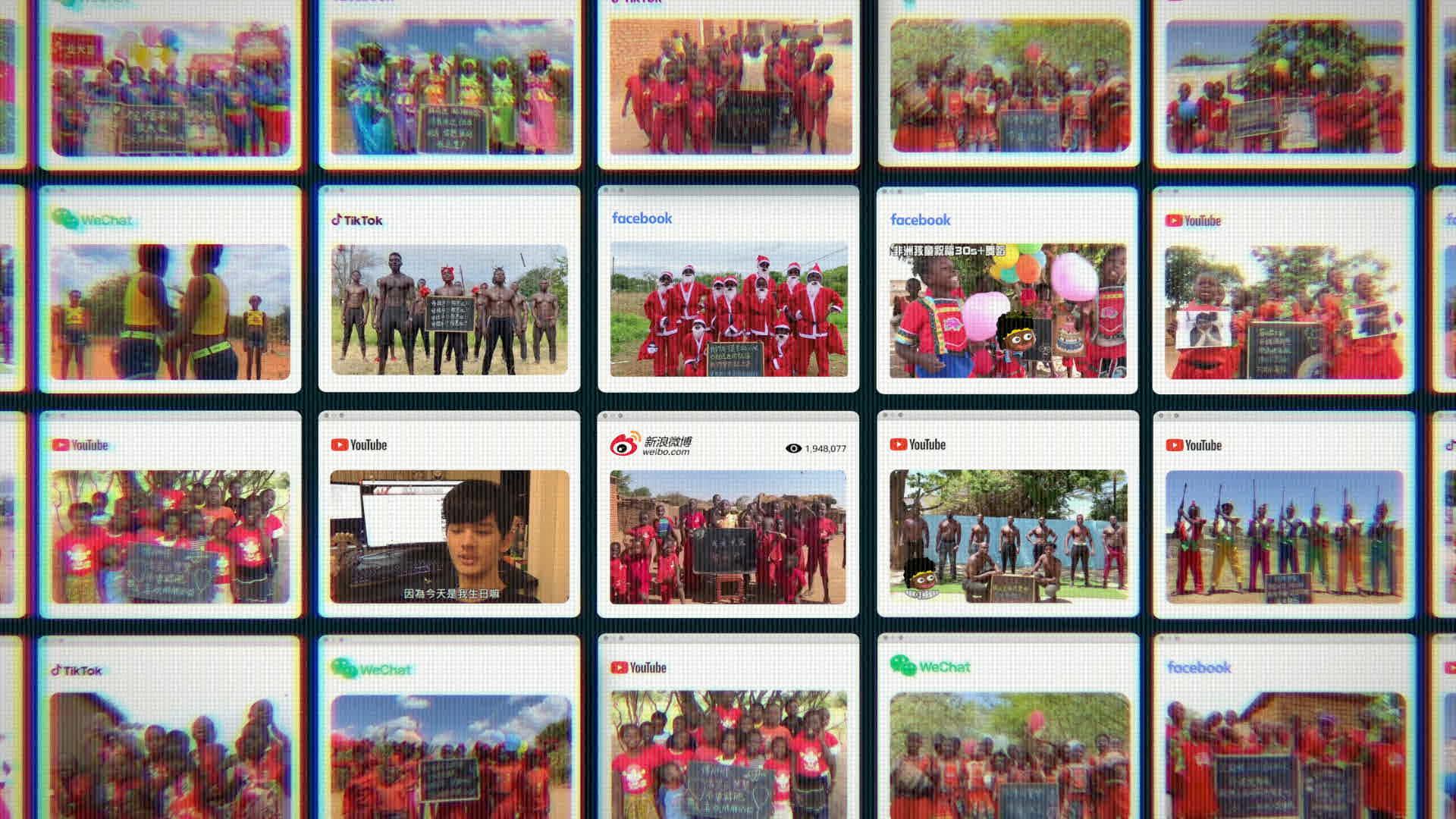

A collage of video screenshots that feature Africans exploited for profit in a growing trend known as “blessings videos.”

During the two-month lockdown in Shanghai this past spring, a very particular kind of entertainment video began to spread on social media, featuring African children taking cues from a voice offscreen to parrot Chinese greetings, word-for-word.

“Wish you win the fight over COVID and the lockdown ends soon,” said one group of African children, who then broke out into dancing.

These are known as “blessings videos,” a growing trend in China over the last seven years that has been criticized for content that exploits Africans for the sake of entertainment.

Runako Celina, a BBC journalist who worked on a new documentary uncovering the people and profits behind the trend, said that entrepreneurs hire crews based in at least seven countries across Africa to produce these videos.

“There are scattered operations across the continent. Many of them work as a network, and they know each other,” Celina said.

Clients pay anywhere from $10 to $70 for a personalized blessings video.

Some who provide this service claim that a portion of the profits go directly to the children involved or to supporting the local community. But they’re not just filming children — some videos feature muscle men, or young women, for example.

Celina and her team pored through hundreds of these videos and said that they might seem innocent at first, but there’s something problematic about them.

“Immediately, it kind of rang alarm bells to me. … It’s just this idea of swanning into someone’s community and sticking a camera in their face and telling them to say whatever you want. You know — it’s a slippery slope.”

“Immediately, it kind of rang alarm bells to me,” she said. “It’s just this idea of swanning into someone’s community and sticking a camera in their face and telling them to say whatever you want. You know — it’s a slippery slope.”

Some videos depict children who are prompted by crew members to use swear words or act in inappropriate ways.

Celina describes a particularly shocking example from 2020: “You see a group of young African children huddled around a blackboard, and they are instructed by someone offscreen to say, in Chinese, ‘I’m a Black monster. My IQ is low.’ Then, at the end of the video, they wave their hands and cheer and smile.”

The documentary followed her and her team as they searched in Malawi for the villages where the video was made and the film crew that made it. What they found was disturbing.

“We’re talking big amounts of money here,” she said. “And in both of the villages that we visited in Malawi, and the children that we spoke to, we saw the same thing. The kids were earning less than half a dollar a day.”

At least one of the children in the documentary reported physical abuse at the hands of the film crew as well.

A growing market

The people who produce these videos say they’re harmless — and there’s growing demand.

Malaysian Zac Koh sells blessings videos on Facebook to clients in Malaysia and China. He said the videos aren’t racist or exploitative — it’s just business.

Koh said he works with up to 40 field crews in Africa as well as in Ukraine and Thailand.

Crews typically work from 10 a.m. until sundown, creating about 200 short videos a day. They try to offer same-day service to clients in Asia. Koh couldn’t say how much the children featured in his videos get paid.

“I can tell you that every month, we take a portion of the money and give it to the kids and it is to build the local economy and give them more work opportunities. The adults get a salary, but I don’t how much either,” he said.

He said that the BBC documentary depicted a boss that “was not very nice,” but that the film crews he works with treat children featured in his videos very well.

Koh said that his clients think videos of Africans dancing are funny and that there’s high demand for this type of entertainment within a growing market across Asia, including Japan.

A call for wider conversations about anti-Blackness

Officials in China and Malawi reacted strongly to the “Racism for Sale” documentary, which came out last week.

They tweeted that there should be no tolerance for racism.

The Chinese man who filmed the racist video in Malawi was arrested in neighboring Zambia. Civic groups in Malawi held a protest, demanding he be tried there and that the children involved be compensated.

Celina said she hopes the film is viewed widely across China.

“There needs to be this wider conversation about anti-Blackness and racism that, in a sense, also underpins this industry,” she said.

On Chinese social media and in anti-discrimination WeChat groups, there have been calls to stop supporting the blessings video industry. But others argue that the videos are innocent, and that they’re actually helping poor communities.

A Chinese woman who has done anti-racism work in the past said the people enjoying the blessings videos are ignorant.

She requested that we not use her name because she has been harassed by authorities for arranging cross-cultural events.

“Even if they are not intentionally being racist, I think the act of commodifying Black people is wrong,” she said.

“But many people here don’t really take this that seriously. They think, ‘everyone looks happy, I’m not hurting anyone.’ They don’t have much interaction with Black people and they haven’t considered how their actions could have an impact on them.”

And she said she hopes that the conversation about racism that the video controversy sparked will continue.