This month, a play called “Ngaahika Ndeenda,” or “I Will Marry When I Want,” was performed for the first time at the Nairobi National Theater in both its original Gĩkũyũ and in English.

“When I heard they were being played again, or it was being played, no matter what format, I was of course happy.”

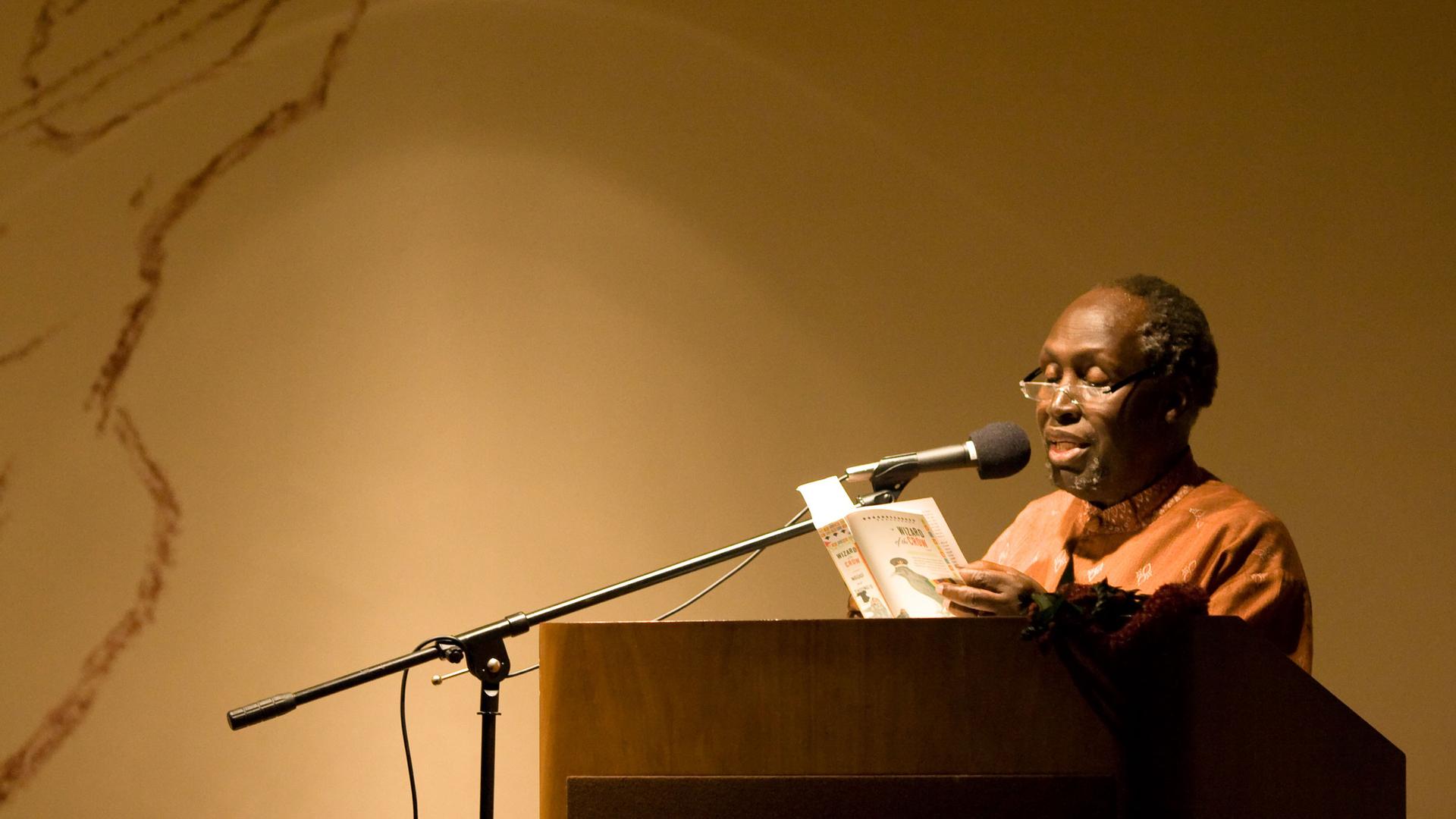

“When I heard they were being played again, or it was being played, no matter what format, I was of course happy,” said legendary Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who co-authored the play with Ngũgĩ wa Mirii in 1977.

It’s come a long way since then.

The play was first conceived through the Kamĩrĩĩthũ Community Education and Cultural Center, which provided adult education and literacy programs for the rural poor.

Thiong’o explained it was a collaboration with the center’s participants, who were able to draw from their real struggles and experiences and use theater as a means of education.

“The theater was going to be very good because they would act in a play and others could come and join,” he said.

But soon after the popular play’s premiere, which had drawn a national audience, it was banned under the government of Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta.

“Kenyatta [put] me into a maximum security prison for writing a play!” Thiong’o chuckled. He was detained for a year without specific charges and later forced into exile. He now lives and teaches in California.

Despite the consequences, Thiong’o said the incident made him realize the power of writing in local African languages, and would go on to write many novels in his native Gĩkũyũ.

Related: Radio Haiti finds a new home with a trilingual archive at Duke University

Even with the ban on this play and other of Thiong’o’s works, it nonetheless attracted generations of activists and artists lured by its progressive social critiques.

Related: ‘They don’t help us’: Apathy, disillusionment with the Kenyan govt blamed for low voter registration

“We’ve all known about it for so long. I knew about it when I was in high school,” said Nice Githinji, an actor with the Nairobi Performing Arts Studio, which produced the play.

“I think it’s a play that most of us growing up, either we read it or knew that it was there,” she said, recalling how they would share a single banned book among progressive students.

Githinji plays a poor, rural woman named Wangechi who, along with her husband, are told by a wealthy Kenyan family that they are living in sin.

They are persuaded into having a proper Christian marriage. In the end, however, they wind up losing their land in their efforts.

For Githinji, it’s a necessary but rare criticism of Christianity and its history in Kenya.

“The thing that keeps on jumping out on the page for me is just how we forgot that we had our traditional ways of praying, we had our traditional ways of speaking to whichever creator is out there. … They just came and shoved the Bible down our throats, and with that came colonialism.”

“The thing that keeps on jumping out on the page for me is just how we forgot that we had our traditional ways of praying, we had our traditional ways of speaking to whichever creator is out there,” Githinji said.

“They just came and shoved the Bible down our throats, and with that came colonialism.”

The play highlights pivotal moments in Kenya’s history, including the brutal violence of British colonialism, exploitation by foreign companies and land grabbing.

Perhaps most controversial, however, is the damning critique of the failures of Kenya’s newly independent government and the collusion of elites in meeting the basic needs of the struggling masses.

“After watching [the play], I understand why he was arrested. It makes so much sense.”

“After watching it, I understand why he was arrested. It makes so much sense,” said 26-year old Mueni Mwando, who was unfamiliar with the history of the play before she attended the premiere.

“It’s such a relevant play,” she added, noting how the dominant theme of inequality in Kenya remains an issue today.

“This is the best time for this play to come back up right now. Because now we have to think about who we are putting in that seat,” said Mwando, referencing Kenya’s upcoming presidential election in August.

Related: Kenyan environmentalists protest proposed forest bill amendments

For Thiong’o, who has lived far from home for decades, the fact that the play can be performed without issue is a sign that Kenya has become more open.

“No society can develop without a vigorous exchange of ideas,” he said.