Haitian radio journalist Jean Dominique was gunned down outside the radio station he owned and ran in Port Au-Prince, on April 3, 2000.

No one knows exactly who was behind the assasination — but Dominique had plenty of enemies.

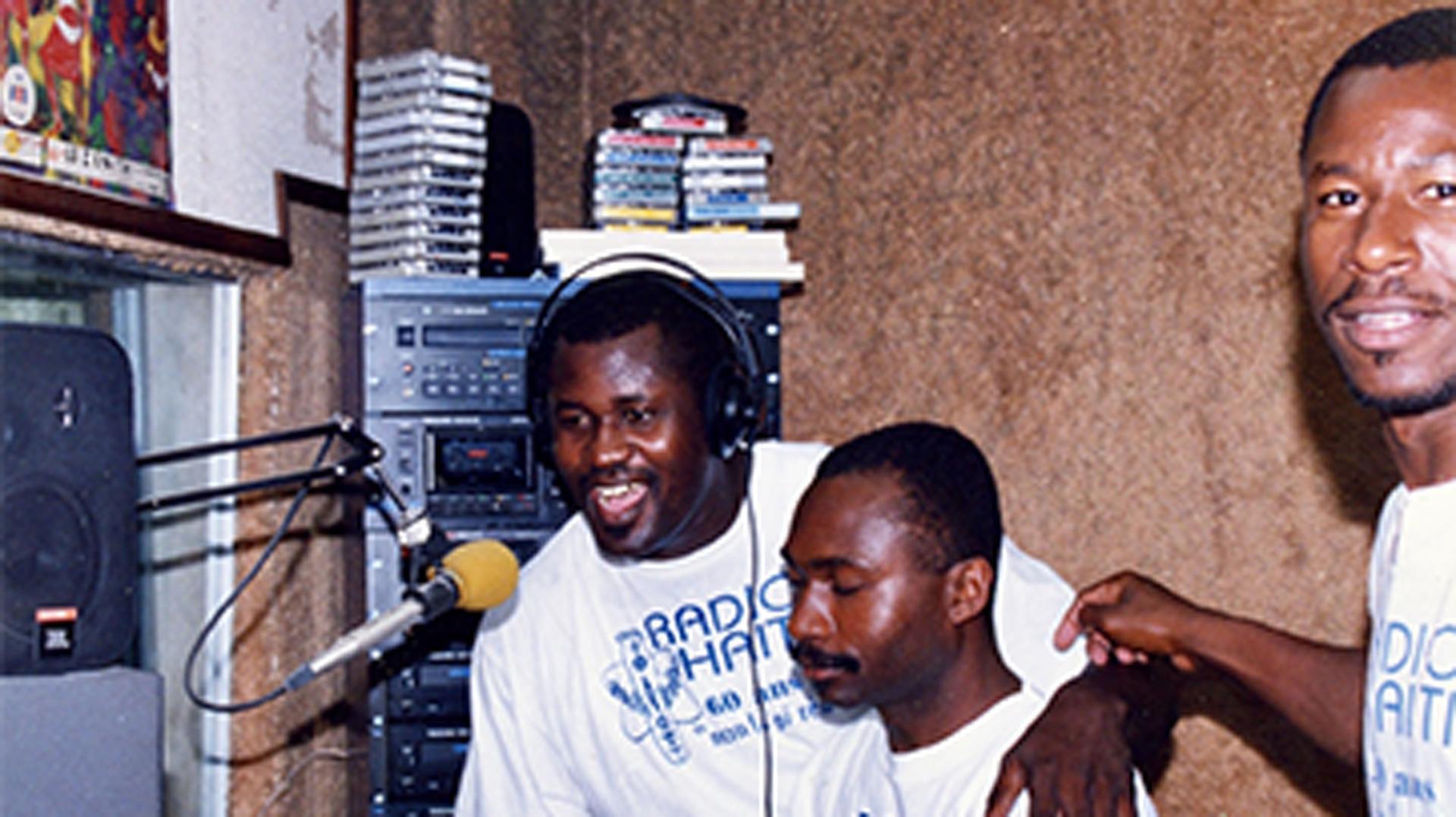

Over four decades, Dominique’s station, Radio Haiti-Inter, championed the stories of the poor and landless — upsetting Haiti’s French-speaking elite. Programs were broadcast not just in French, but also in Haitian Creole, the universal language in Haiti, spoken by rich and poor alike. The station shut down soon after Dominique’s death.

That trove of audio material has now found a second life in the form of a trilingual archive at Duke University. The collection includes audio and videotapes in French, Haitian Creole and English — dating all the way to 1957.

Related: This Haitian schoolteacher helps new arrivals from Haiti resettle in Arizona

Centering Haitian Creole

Before Radio Haiti, Haitian Creole was only heard on the airwaves for commercials.

But Dominique and his wife, Michèle Montas, gradually began to center Haitian Creole in their news coverage, starting with cultural programs.

In 1972, alongside his sister, Madeleine Paillère, Dominique adapted “Gouverneurs de la Rosée,” or “Masters of the Dew,” a well-known novel written in French about farmworkers rising up and organizing against their oppressive landowners in Haiti. It kept the French narration but translated the dialogue into Haitian Creole.

Because it was fictional, Montas said that it didn’t bother Haitian authorities.

“Talking about actual events happening would have worried [Haitian authorities].”

“Talking about actual events happening would have worried them,” Montas said.

Montas ran Radio Haiti’s newsroom for decades. After Dominique’s assassination, she took on a more public-facing role but attacks and threats forced her to eventually shut the station down in 2003.

Montas said that hearing Haitian Creole language gave ordinary Haitians a sense of belonging — to the radio station and to society at large.

Haitian Creole emerged out of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in the 17th and 18th centuries, when hundreds of thousands of African people were enslaved in Saint Domingue, the French colony that later became Haiti.

Enslaved people came from different ethnic and linguistic groups across Africa and did not share a common language, according to Laura Wagner, the founding director of Radio Haiti archives at Duke University.

Haitian Creole emerged in order to communicate, Wagner said, and this allowed them to eventually organize among themselves against their enslavers.

Some Haitian Creole speakers prefer to call the language Kreyòl because it is a fully developed language. In linguistics, a creole is less grammatically stable.

Montas said that Haitian Creole comes most naturally to Haitians, including herself.

Growing up, Montas said that she spoke French with her parents and Haitian Creole with her nanny.

“At school, we spoke French to the teachers,” she said. “When we were out playing in the yard, we would speak [Haitian] Creole to each other. Of course, we were punished for it, but we did anyway.”

‘Brilliant and fearless’

Dominique bought Radio Haiti in the 1960s, when the country was under a dictatorship.

“[Jean Dominique] was this brilliant, fearless journalist and activist.”

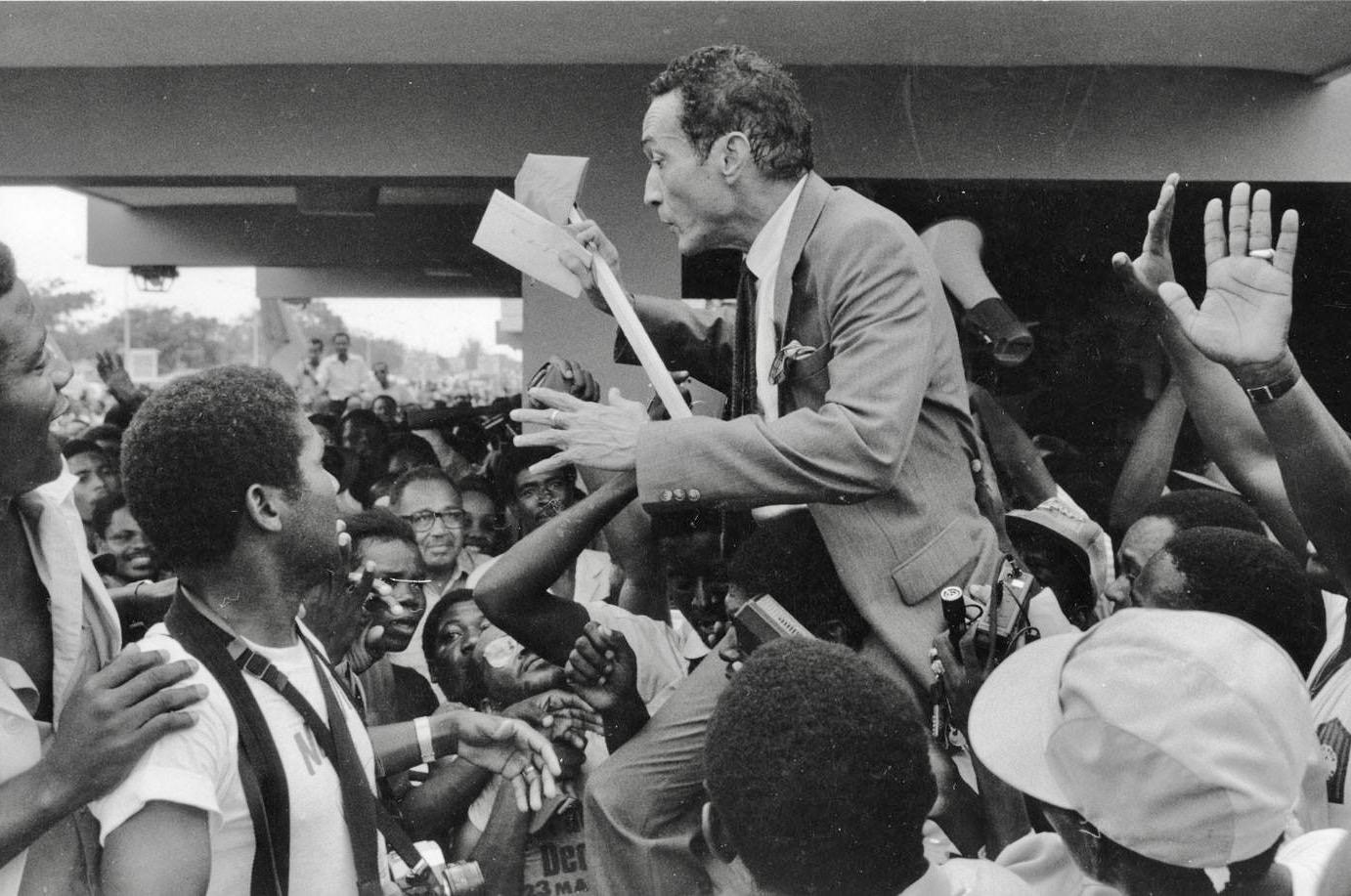

“He was this brilliant, fearless journalist and activist,” Wagner said.

Dominique was akin to broadcast journalist Edward R. Murrow, in that he was “the most-recognized voice in Haitian media,” according to Wagner. And like American journalist and civil rights leader Ida B. Wells, she said, he was “doing investigations while also speaking truth to power.” He also “focused on the lives of ordinary people,” she said, comparing him to American writer Studs Terkel.

When Dominique spoke, people listened, Wagner said.

Dominique liked to talk, but he was also a keen listener, especially to marginalized people, Wagner said.

He liked to say, “I need to sit on my school bench and learn from the people.”

In “The Agronomist,“a documentary about Dominique’s life, he can be heard in an outtake talking about the plight of Haiti’s poor and landless people.

“Six million people. … Poor, illiterate, Black, dirty. At the bottom of human life. But this country has something to tell you.”

“Six million people,” Dominique said in his emphatic style, punching each word.

“Poor, illiterate, Black, dirty. At the bottom of human life. But this country has something to tell you.”

Related: Meet the trusted guide to Port-au-Prince’s streets

For Haitians, in Haiti

Dominique’s spirit lives on in the trilingual archives of Radio Haiti at Duke University today.

“It was extremely important to me when I donated Radio Haiti’s archives to Duke University that the audio archives be made available to Haitians in Haiti,” Montas said.

Related: ‘Haitians deserve a chance to determine their own future,’ former US envoy says

Wagner herself learned to speak Haitian Creole in her 20s and became a fluent speaker by the time she met Montas at Duke University more than a decade after Dominique’s assassination.

Montas said that Wagner’s decision to introduce each recording in English, French and Haitian Creole was exactly what she wanted.

Related: ‘Haitians deserve a chance to determine their own future,’ former US envoy says

That decision — to provide descriptions in Haitian Creole of 5,000 separate audio files — has made a difference for the many Haitians who couldn’t read French or English.

“The [Haitian] Creole description meant access. … It also meant respect for the language that had had no respect before.”

“The [Haitian] Creole description meant access,” Montas said. “It also meant respect for the language that had had no respect before.”

But those involved in the project recognize that little has improved for the Haitian Creole language or its speakers in Haiti.

Montas said that in some ways, things have gone backward.

The voices of poor Haitian Creole speakers are still excluded from the national conversation, she said.

But at least Radio Haiti’s archive is now preserved and accessible as a beacon of possibility.

“Subtitle,” a podcast about languages and the people who speak them, produced an episode about Radio Haiti and its archive. The podcast is supported by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.