The pandemic has brought about the largest global vaccination effort in history.

An estimated 15 billion injections happen each year around the world. During the pandemic, that number has nearly doubled.

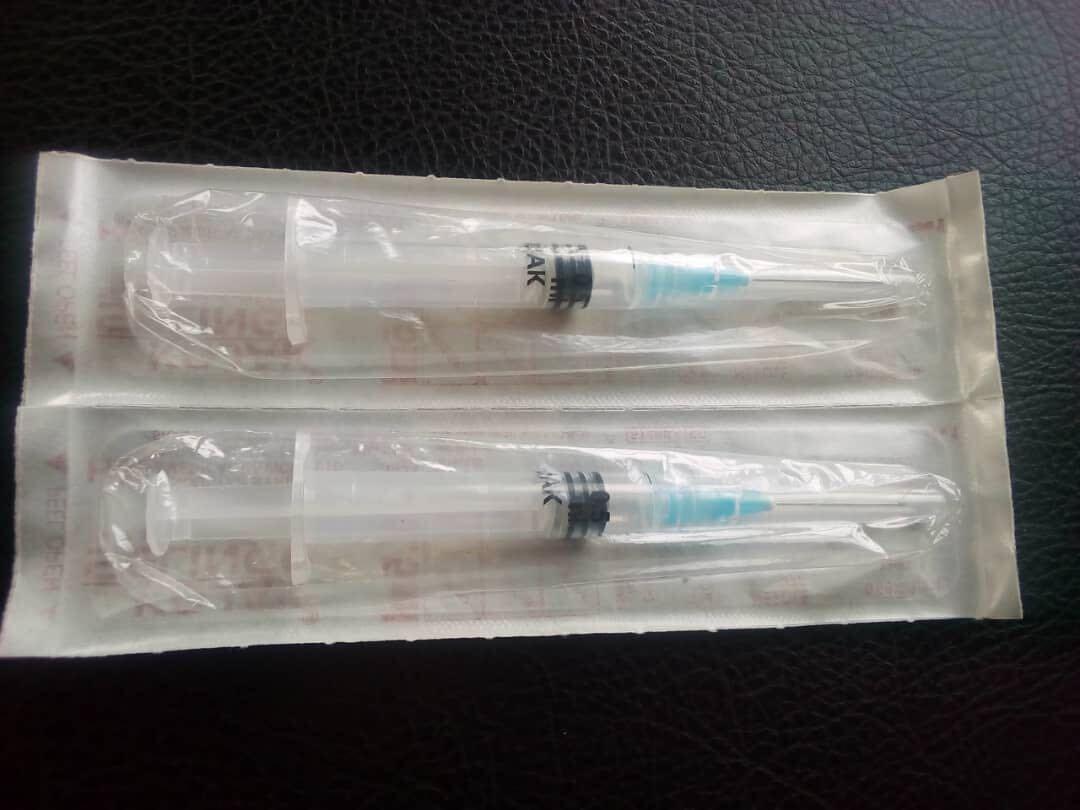

But COVID-19 vaccinations use a special kind of syringe that many worry could be in short supply. In late 2021, UNICEF projected a shortfall of up to 2 billion auto-disable (AD) syringes for this year.

Related:Why Chile moved ahead with COVID vaccines for the very young

Roneek Vora, the sales director with Revital Healthcare, a family-owned medical supplier in Kenya, said the demand for syringes is overwhelming.

“We have doubled our capacities based on the demand and we’re looking to triple our capacities before the end of this year.”

“We have doubled our capacities based on the demand, and we’re looking to triple our capacities before the end of this year,”he said.

AD syringes have become the gold standard for immunization campaigns and injection safety around the world. They emerged in the 1990s amid a global push to improve injection safety and education in low- and middle-income countries where community workers often give vaccines outside clinics.

AD syringes have features that prevent reuse, automatically locking once the injection begins or ends, depending on the type. It may break if an attempt is made to reuse it, or the needle may automatically retract. The kind used for immunizations is designed for a fixed dose — to make it easy for community workers to draw the exact amount of vaccine.

But there’s a mismatch between the size of the standard .5-milliliter AD syringe and Pfizer’s smaller-than-average COVID-19 vaccine dose of .3milliliters.

Moderna and Pfizer’s pediatric doses require custom-made AD syringes, as does Moderna’s booster dose. This month, the World Health Organization called on vaccine makers to prioritize standard dose volumes when developing vaccines, and to scale up production of customized AD syringes.

Neither Pfizer nor BioNTech responded to multiple interview requests.

For global vaccination efforts that rely on AD syringes, this mismatch between the dose and the syringe type can create further logistical headaches.

The limited availability right now means some campaigns may have to use flexible dose syringes — which have some safety features and require more training.

Related:Ghana revs up its COVID-19 vaccination campaign as omicron cases surge

At the same time, companies like Revital in Kenya are working to fill the overall gaps. Revital is one of the only companies in Africa that makes AD syringes, and the only one on the continent that has been authorized through the World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund.

Vora, Revital’s sales director, hopes to get authorized soon in order to supply those smaller syringes needed for Pfizer’s vaccine.

“The whole purpose behind establishing this industry is to ensure that Kenya and Africa as a continent become self-reliant,” he said.

Global health workers still remember the days when reusable syringes were used; itproduced less medical wastebut brought a lot more risks, according to Lisa Hedman, who oversees supplies and access to medicines at WHO.

Over the years, contaminated injections and syringe reuse led to a lot of deaths and disability from infectious diseases like HIV and hepatitis, she said, even where it seemed like enough regular syringes were available.

“There’s some belief that if you have enough, this isn’t the problem. People won’t reuse if you have enough. But when you saw the number of infections related to immunization campaigns, you actually have to do something to ensure that the injections are safe.”

“There’s some belief that if you have enough, this isn’t the problem. People won’t reuse if you have enough. But when you saw the number of infections related to immunization campaigns, you actually have to do something to ensure that the injections are safe,” she said.

One report found that in the year 2000, contaminated injections caused some 20 million hepatitis B infections, 2 million hepatitis C infections, and a quarter of a million HIV infections.

Josephine Babirye, a nurse and assistant district health officer in the rural district of Luuka in Uganda, said AD syringes are widely accepted because they’re simple and safe.

“[Auto-disable syringes] come when they are already sterilized, they are ready to use, attached together with the needle.”

“They come when they are already sterilized, they are ready to use, attached together with the needle,” she said.

In fact, they are the only type used by health workers in the country.

Hedman said that with the pandemic, more AD syringes are urgently needed.

“We don’t actually have manufacturing capacity for this particular type of syringe where we can just ramp up and say, ‘OK, we’re just going to increase production of these products,’” she said.

Even as syringe makers around the world scale up and help alleviate short-term concerns, the need for boosters and possible new COVID-19 vaccine formulas makes it hard to plan for enough future syringes, Hedman said.

They’re still needed for non-COVID-19 immunization campaigns and new malaria and HIV treatments. InPakistan, health workers are also switching to auto-disable syringes more broadly in health care.

Vora with Revital in Kenya said that she doesn’t expect this work to slow down anytime soon.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?